Why Do Teens Vape? New Research Reveals Hidden Brain Changes

Introduction

Despite increasing public awareness of the health risks associated with nicotine use, vaping remains highly prevalent among adolescents. According to 2024 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 8.1 percent of United States middle and high school students, representing approximately 2.25 million individuals, reported current use of at least one tobacco product, while 19 percent, or 5.28 million students, reported lifetime use. Over the past decade, electronic cigarettes have overtaken combustible cigarettes as the most commonly used nicotine product among adolescents, with use peaking in 2019 when 27.5 percent of high school students reported vaping. Although prevalence has declined modestly since that peak, adolescent vaping continues to represent a major public health concern.

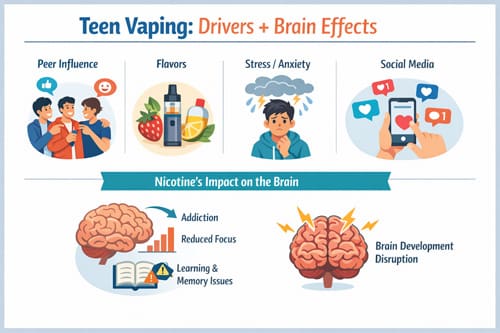

The persistence of vaping among teens is particularly troubling when viewed through the lens of adolescent neurodevelopment. The teenage brain undergoes significant structural and functional maturation, particularly within the prefrontal cortex and reward circuitry. Nicotine exposure during this critical developmental period has been shown to alter neurotransmitter systems involved in attention, learning, impulse control, and emotional regulation. Emerging neurobiological evidence links adolescent nicotine exposure to long-term cognitive deficits, increased risk of mood and anxiety disorders, and heightened susceptibility to future substance use. These effects appear to be more pronounced in adolescents than in adults, reflecting increased neuroplasticity and vulnerability during this stage of development.

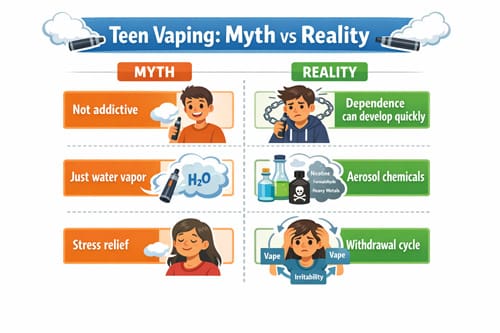

Dependence can also develop rapidly in adolescents who vape, even with intermittent or experimental use. Studies indicate that teens may experience symptoms of nicotine addiction earlier and at lower levels of exposure than adults. This heightened sensitivity helps explain why many adolescents transition quickly from occasional vaping to regular use, often before recognizing the signs of dependence. Compounding this concern, longitudinal research has demonstrated a consistent association between adolescent e-cigarette use and subsequent initiation of combustible cigarette smoking, suggesting that vaping may serve as a gateway to broader nicotine and tobacco use.

Among adolescents who report current vaping, more than 87 percent indicate using flavored e-cigarette products. Flavor availability remains one of the most influential factors driving adolescent uptake, as sweet, fruity, and mint flavored products mask nicotine harshness and enhance appeal. However, the reasons teens vape extend well beyond flavoring alone. Social influences such as peer norms, social media exposure, targeted marketing, and perceived social acceptance play a substantial role. Psychological factors including stress, anxiety, sensation seeking, and misperceptions about harm reduction further contribute to experimentation and sustained use.

This article examines the question of why teens continue to vape despite well publicized health warnings by integrating epidemiological data with insights from neuroscience, behavioral science, and public health research. By exploring the intersecting biological, social, and psychological drivers of adolescent vaping, the discussion aims to inform clinicians, educators, and policymakers seeking to design more effective prevention, screening, and intervention strategies tailored to this uniquely vulnerable population.

Nicotine and the Teenage Brain: What New Research Shows

Recent neuroscience research reveals alarming evidence about nicotine’s impact on the developing adolescent brain, offering critical insights into why teens who vape face unique neurobiological risks.

Prefrontal Cortex Disruption from Early Nicotine Exposure

The prefrontal cortex (PFC), responsible for attention regulation and behavioral control, remains incompletely developed throughout adolescence. This developmental vulnerability makes it especially susceptible to nicotine’s neurotoxic effects. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) play essential roles in brain maturation from prenatal development through adolescence, with expression patterns that parallel key developmental events in the cholinergic system [1].

Nicotine exposure specifically alters acetylcholine and glutamate signaling receptors that facilitate nerve cell communication from the PFC [2]. These molecular alterations affect functional synapses in ways that potentially impact permanent cognitive capacity. Additionally, adolescent nicotine exposure reduces presynaptic mGluR2 protein on excitatory synapses in the prefrontal cortex, which alters the rules for spike timing-dependent plasticity in prefrontal networks [3].

Consequently, teens who vape experience structural and functional neural changes that potentially persist into adulthood. Animal studies have confirmed that adolescent (but not adult) nicotine exposure induces profound neuroadaptations in the PFC that remain detectable long after exposure ends [4].

Changes in Dopamine Pathways and Reward Sensitivity

Nicotine fundamentally rewires the brain’s reward system through alterations in dopamine pathways. In fact, nicotine exposure leads to notable changes in levels of neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin [5]. The adolescent brain shows heightened sensitivity to these effects as demonstrated by research revealing that adolescent rodents are more responsive than adults to nicotine’s rewarding properties [1].

Remarkably, adolescent rats exhibit greater dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens in response to acute nicotine compared to adult counterparts, even with similar baseline measures [6]. Moreover, nicotine exposure during adolescence (PND 34-43) increases electrically evoked dopamine release in the prefrontal cortex of adult animals—an effect associated with enduring cognitive deficits including reduced attention and increased impulsivity [6].

These neurochemical changes may help explain why teens vape so much once they start. The enhanced reward sensitivity creates a stronger foundation for dependence. Interestingly, these alterations show sex-specific patterns, with varying changes in dopamine receptor expression between males and females following adolescent nicotine exposure [6].

Cognitive Impairments Linked to Adolescent Vaping

The cognitive consequences of vaping in teens extend beyond temporary effects. Studies comparing e-cigarette users to non-users have identified that adolescents who used e-cigarettes reported poorer academic self-efficacy (t(430) = 3.26, p < 0.001), greater mind-wandering tendencies (t(430) = -3.38, p < 0.001), and greater severity of depression, anxiety, and stress [7].

A concerning dose-response relationship emerges from research examining college students: those who vaped more than 20 puffs daily scored 13.7% lower on cognitive function tests than non-vapers, whereas students vaping 10-20 puffs showed a 9.2% decrease [8]. Moreover, increased frequency of e-cigarette use correlates with lower academic self-efficacy (r(86) = -0.27, p = 0.010) [7].

Animal research provides additional evidence—rats exposed to e-cigarette aerosol demonstrate impaired learning and both short- and long-term memory deficits [7]. Notably, these cognitive impairments occur even in the absence of nicotine, suggesting other components in e-cigarette aerosols may contribute to neurocognitive harm [7].

The adolescent brain’s vulnerability to these effects stems from its developmental stage. As adolescence represents a critical period of major plasticity in brain systems regulating motivated behavior and cognition, nicotine exposure during this window can produce long-lasting effects that would not occur from similar exposure in adulthood [1].

Why Do Teens Vape? Psychological and Social Drivers

Understanding the complex factors that drive adolescent vaping requires examination beyond neurobiological vulnerability. Motivational factors, social contexts, and psychological needs all contribute to answering the question: why do teens vape?

Peer Influence and Social Media Normalization

Peer relationships exert powerful influence on teen vaping initiation. A striking 60% of adolescents report obtaining their first e-cigarette from friends, with 54% trying their first device while “hanging out with friends” [9]. This social pathway to vaping demonstrates how friend circles create entry points for experimentation. Research indicates that teens who report having best friends who vape show dramatically increased risk of initiation—those reporting all best friends vape were 4.08 times more likely to start vaping themselves [10].

Online environments equally shape vaping behaviors. Approximately 53.6% of e-cigarette users report exposure to vaping advertisements in a three-month period, with most of this content encountered through social media [9]. Studies reveal adolescents who view e-cigarette content on platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube demonstrate increased likelihood of subsequent use [11]. Exposure to influencer posts appears particularly influential, with teens who see influencer e-cigarette content showing higher rates of both current use and dual use of cannabis and e-cigarettes [11].

Flavored Products and Perceived Harmlessness

Nearly 90% of youth e-cigarette users consistently select flavored products, with fruit, candy, mint, and menthol reported as most popular choices [12]. E-cigarette manufacturers capitalize on this preference through youth-oriented product designs and flavor profiles with names like “Chewy Clouds Sour Grape” and “Killer Kustard Blueberry” [13].

Though flavors initially attract teens, perceived safety reinforces continued use. Research shows adolescents often underestimate e-cigarette risks—approximately 55.5% of youth reported e-cigarettes as “not at all” addictive [14]. Current e-cigarette users demonstrated 4.77 times higher odds of viewing e-cigarettes as “not at all” harmful compared to non-users [14]. This perception gap represents a critical factor in explaining vaping prevalence among teens initially considered at low risk for tobacco use [15].

Stress, Anxiety, and Self-Medication Behaviors

Psychological factors play a crucial role in teen vaping behaviors. An overwhelming 81% of young e-cigarette users report starting to vape to decrease stress, anxiety, or depression [3]. Among frequent vapers, 50.3% indicate they need e-cigarettes to cope with emotional distress [3].

Ironically, rather than alleviating mental health concerns, research indicates vaping may worsen them:

- 60% of nicotine-only and dual vapers report experiencing anxiety symptoms versus 40% of non-vapers [16]

- Over 50% of all vaping groups report suicidal thoughts within a year, compared to one-third of non-users [16]

- Youth with elevated anxiety appear increasingly vulnerable to substance use, partly because nicotine is perceived as stress-relieving [17]

This self-medication cycle becomes particularly concerning for adolescents with adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Research shows teens with four or more ACEs were 20% less likely to quit vaping, with each additional experience of abuse associated with a 7% decrease in abstinence [18]. The nicotine withdrawal cycle itself perpetuates misperceptions about stress relief—withdrawal symptoms like irritability and anxiety temporarily diminish with nicotine use, creating a false association between vaping and emotional regulation [3].

Behavioral and Digital Tools for Teen Vaping Cessation

As healthcare providers confront persistent teen vaping trends, effective intervention tools become increasingly crucial. Recent research highlights several evidence-based approaches that address both the behavioral and technological aspects of adolescent nicotine cessation.

Motivational Interviewing in Pediatric Settings

Motivational interviewing serves as a foundational approach for clinicians working with adolescents who vape. This technique functions effectively through both individual and group counseling sessions, becoming an essential component of comprehensive cessation plans [4]. For youth who initially lack motivation to quit, ongoing motivational interviewing during scheduled follow-up visits allows clinicians to support gradual change [4].

Clinical assessments of readiness to quit, motivation levels, and potential barriers must precede behavioral interventions [2]. Even when teens resist setting a quit date, conversations exploring their reasons for vaping help build motivation incrementally [2]. These discussions become particularly valuable for understanding the unique factors behind why teens vape so much despite health warnings.

Text-Based Programs: MyLifeMyQuit and This Is Quitting

Text-based interventions demonstrate remarkable effectiveness for vaping in teens. Adolescents enrolled in Truth Initiative’s text message-based program were 35% more likely to quit vaping nicotine within seven months compared to control groups [19]. The program showed success even among highly addicted teens—76.2% of participants used e-cigarettes within 30 minutes of waking, and 93.6% reported feeling somewhat or very addicted [19].

Two prominent text-based programs stand out:

- My Life, My Quit: This free, confidential service offers five one-on-one coaching sessions typically scheduled 7-10 days apart [20]. Coaches employ motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral techniques specifically designed for adolescents [20]. The program includes watermarked completion certificates for teens completing the program as an alternative to disciplinary action [20].

- This Is Quitting: Developed by Truth Initiative, this program has helped over 300,000 youth quit vaping [1]. It incorporates peer messages from others who have attempted or successfully quit e-cigarettes, tailored by age (13-24) and product usage [1]. Teens can join by texting “DITCHVAPE” to 88709 [1].

Gamified Apps and School-Based Support Programs

Gamification elements in cessation apps correlate with increased self-efficacy and motivation to quit. Research indicates that the average perceived frequency of gamification features significantly associates with changes in self-efficacy (β=3.35; 95% CI 0.31-6.40) and motivation to quit (β=.54; 95% CI 0.15-0.94) [6]. Goal setting emerged as the most useful gamification feature, whereas sharing was perceived least useful [6].

Additionally, school-based programs offer structured support through:

- INDEPTH: An alternative to suspension for students caught vaping at school, this four-session program teaches about nicotine dependence and healthy alternatives rather than focusing on punishment [21].

- N-O-T (Not On Tobacco): This 10-session program takes a holistic approach, using interactive learning strategies to encourage voluntary behavior change in youth ages 14-19 [21].

Regular physical exercise and prosocial activities further support cessation attempts, provided they don’t involve peers who vape [4]. The most effective treatment plans remain individualized, incorporating elements teens themselves believe will be helpful in their quest to stop vaping [4].

Pharmacologic Support: What Works and What Doesn’t

Pharmacologic interventions for teen vaping cessation present unique challenges for clinicians working with youth nicotine dependence. Unlike adult protocols with established medications, adolescent treatment remains largely uncharted territory with limited evidence-based options.

Nicotine Replacement Therapy in Adolescents

NRT represents the most commonly considered pharmacologic option for adolescents struggling with vaping cessation, albeit without FDA approval for this population. Research indicates teens typically prefer NRT patches over gum or lozenges; nevertheless, adherence rates remain problematic with studies showing only 15.5% of adolescents using patches consistently as prescribed. NRT effectiveness in this population appears modest at best—one systematic review found a non-significant trend toward short-term abstinence with patches compared to placebo.

Risk-Benefit Assessment and Informed Consent

Clinicians must carefully weigh several factors prior to considering off-label NRT for adolescents who vape:

- Severity of nicotine dependence (frequency of use, time to first use after waking)

- Previous failed quit attempts with behavioral interventions alone

- Patient motivation to quit

- Family support systems

- Potential for medication misuse

Given the absence of strong efficacy data, informed consent becomes paramount. Both adolescents and their parents/guardians require thorough discussion regarding uncertain benefits, potential adverse effects, and the off-label nature of any pharmacotherapy. Practically speaking, clinicians should document these conversations extensively in medical records.

Lack of FDA-Approved Medications for Teen Use

Currently, no cessation medications carry FDA approval for adolescents under 18—not NRT, bupropion, nor varenicline. This regulatory gap stems primarily from insufficient clinical trials in youth populations. Indeed, a recent assessment of clinical trials for smoking/vaping cessation reveals that children and adolescents remain systematically excluded from most studies.

The absence of FDA-approved options ultimately places clinicians in difficult positions, forcing individualized risk-benefit analyzes without established guidelines. Research specifically targeting effective pharmacotherapy for adolescents who vape remains an urgent priority, as current options predominantly rely on behavioral interventions first, reserving pharmacologic support for severe cases unresponsive to other approaches.

Systemic Barriers and Innovations in Clinical Practice

Effective clinical intervention for teen vaping faces substantial systemic hurdles that practitioners must navigate to adequately address this growing health concern among adolescents.

Underreporting Due to Confidentiality Concerns

Confidentiality issues represent a major obstacle in accurate assessment of adolescent vaping behaviors. Teens frequently withhold information about their e-cigarette use, primarily fearing parental discovery or potential repercussions. Many adolescents explicitly indicate they do not want teachers, sports coaches, or parents involved in vaping cessation efforts [22]. This reluctance stems from concerns about getting in trouble and being “labeled” within their school environment. Furthermore, youth often express reluctance to participate in cessation programs due to embarrassment about admitting addiction [22]. This underreporting challenge is exacerbated in clinical settings where parents might observe screening procedures or overhear discussions, prompting adolescents to provide dishonest responses even during confidential health assessments.

Lack of Adolescent-Specific Screening Tools

Despite vaping’s prevalence among teenagers, standardized screening tools specifically validated for adolescent e-cigarette use remain underdeveloped. Several factors complicate consistent identification:

- Limited integration of structured vaping assessments into routine pediatric clinical workflows [7]

- Competing clinical priorities during time-constrained preventive visits [7]

- Provider-reported deficits in training and confidence addressing substance use [7]

The American Academy of Pediatrics accordingly recommends implementing structured screening beginning in early adolescence, with tools like the CRAFFT questionnaire representing one validated option for substance use assessment [7]. Henceforth, initiatives like AVERT have emerged, offering risk assessment tools developed specifically with input from community members to evaluate teen vaping risk levels [23].

Pediatric Vaping Cessation Clinics: A New Model

Responding to these challenges, innovative clinical models are emerging. Cleveland Clinic, for instance, is developing a dedicated Pediatric Vaping Cessation Clinic led by pediatric pulmonologists offering individualized medical evaluations with evidence-based counseling [7]. Otherwise, programs like “NOT for Me” provide holistic approaches addressing nicotine dependence through interactive learning strategies based on Social Cognitive Theory [8]. This 10-session format demonstrates approximately 90% success rates for cutting back or quitting tobacco altogether [8]. Subsequently, these specialized clinics represent an essential evolution in clinical practice, delivering targeted interventions for a population whose unique needs remain insufficiently addressed by traditional cessation methods.

Conclusion

Adolescent vaping continues to present multifaceted challenges for healthcare providers despite growing awareness of its detrimental effects. Research firmly establishes that nicotine exposure during adolescence creates profound neurobiological alterations, particularly in prefrontal cortex development and dopamine reward pathways. These changes manifest as measurable cognitive deficits, with dose-dependent relationships between vaping frequency and diminished academic performance. Teens face exceptional vulnerability during this critical developmental window when compared to adults exposed to identical substances.

Social factors undoubtedly drive initiation patterns, with peer influence serving as the primary gateway to first-time use. Simultaneously, social media platforms amplify exposure to pro-vaping content, thereby normalizing these behaviors among adolescent populations. The perception of harmlessness, coupled with attractive flavoring options, further complicates prevention efforts. Additionally, many teens report using e-cigarettes as self-medication for psychological distress, unwittingly entering a cycle that often worsens the very symptoms they seek to alleviate.

Though intervention challenges abound, several promising approaches have emerged. Motivational interviewing techniques show particular promise in clinical settings when practitioners acknowledge the unique factors driving teen vaping behaviors. Text-based programs such as “This Is Quitting” and “My Life, My Quit” demonstrate measurable success rates by meeting adolescents through their preferred communication channels. Gamified applications likewise offer engaging tools that enhance self-efficacy and motivation to quit.

Pharmacologic options remain limited, however, as no current cessation medications have received FDA approval for adolescents under 18 years of age. This regulatory gap forces clinicians to make difficult risk-benefit assessments when considering off-label nicotine replacement therapy for severely dependent teens. Therefore, thorough informed consent discussions with both adolescents and parents become essential components of ethical practice.

Clinical care faces substantial structural barriers, including adolescent reluctance to disclose vaping behaviors due to confidentiality concerns. The absence of standardized, validated screening tools specifically designed for adolescent e-cigarette use further hampers early identification efforts. Specialized pediatric vaping cessation clinics represent an encouraging development in addressing these gaps, albeit with limited availability nationwide.

Future progress depends on developing evidence-based interventions tailored specifically to adolescent needs rather than adapting adult cessation protocols. Practitioners must balance confidentiality with parental involvement while recognizing the neurobiological vulnerability that distinguishes teenage nicotine dependence from adult patterns. Above all, effective approaches acknowledge the complex interplay of neurological, psychological, and social factors driving the epidemic of teen vaping, thus requiring equally sophisticated, multidisciplinary intervention strategies.

Key Takeaways

New research reveals why teens are uniquely vulnerable to vaping addiction and provides evidence-based strategies for intervention and prevention.

- Vaping rewires developing teen brains: Nicotine exposure during adolescence permanently alters prefrontal cortex development and dopamine pathways, causing lasting cognitive impairments and increased addiction vulnerability.

- Social factors drive initiation: 60% of teens get their first e-cigarette from friends, while social media exposure to vaping content significantly increases likelihood of use among adolescents.

- Self-medication backfires: 81% of teen vapers start to reduce stress and anxiety, but research shows vaping actually worsens mental health symptoms and increases suicidal thoughts.

- Text-based programs show promise: Digital interventions like “This Is Quitting” increase quit rates by 35%, offering accessible support through teens’ preferred communication channels.

- No FDA-approved medications exist: Unlike adult cessation, no pharmacologic treatments are approved for teens under 18, forcing clinicians to rely primarily on behavioral interventions and off-label options.

The adolescent brain’s unique vulnerability during this critical developmental period makes teen vaping a distinct medical concern requiring specialized, age-appropriate intervention strategies rather than adapted adult protocols.

Frequently Asked Questions:

FAQs

Q1. How does vaping impact the developing teenage brain? Vaping during adolescence can cause significant changes to the brain, particularly in the prefrontal cortex and dopamine pathways. This can lead to long-term cognitive impairments, increased risk of addiction, and alterations in mood regulation and impulse control.

Q2. Why are teenagers particularly vulnerable to vaping addiction? Teenagers are uniquely susceptible to nicotine addiction due to their ongoing brain development. The adolescent brain shows heightened sensitivity to nicotine’s rewarding properties, making it easier for teens to become dependent even with intermittent use.

Q3. What are the main reasons teens start vaping? Teens often start vaping due to peer influence, social media normalization, attraction to flavored products, and the perception that e-cigarettes are harmless. Many also use vaping as a way to cope with stress, anxiety, or depression.

Q4. Are there effective ways to help teens quit vaping? Yes, several approaches have shown promise. Text-based programs like “This Is Quitting” have increased quit rates by 35%. Motivational interviewing techniques, gamified apps, and school-based support programs can also be effective in helping teens quit vaping.

Q5. Can medications help teenagers stop vaping? Currently, there are no FDA-approved medications for vaping cessation in teens under 18. While nicotine replacement therapy is sometimes used off-label, its effectiveness in adolescents is limited. Treatment primarily relies on behavioral interventions tailored to teens’ specific needs.

References:

[1] – https://www.nbhnetwork.org/resources/this-is-quitting-by-truth-initiative/

[2] – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1555415523002532

[3] – https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/emerging-tobacco-products/colliding-crises-youth-mental-health-and-nicotine-use

[4] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6931901/

[5] – https://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/our-health/be-healthy-blog/how-does-nicotine-affect-brain-development

[6] – https://games.jmir.org/2021/2/e27290/

[7] – https://consultqd.clevelandclinic.org/addressing-nicotine-dependence-in-pediatric-populations

[8] – https://www.lung.org/quit-smoking/helping-teens-quit/not-on-tobacco

[9] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8296881/

[10] – https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2796834

[11] – https://keck.usc.edu/news/e-cigarette-and-cannabis-social-media-posts-pose-risks-for-teens-study-finds/

[12] – https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/emerging-tobacco-products/sales-flavored-e-cigarettes-continue-rise-state

[13] – https://www.ama-assn.org/about/leadership/flavored-e-cigarettes-pose-dire-threat-youth-and-public-health

[14] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5049876/

[15] – https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2018/17_0368.htm

[16] – https://newsroom.heart.org/news/depression-anxiety-symptoms-linked-to-vaping-nicotine-and-thc-in-teens-and-young-adults

[17] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9560985/

[18] – https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/quitting-smoking-vaping/new-study-teen-e-cigarette-users-childhood-trauma-need

[19] – https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/quitting-smoking-vaping/text-message-program-truth-initiative-helps-teens-quit-e

[20] – https://mylifemyquit.com/en-us/resources/educators/

[21] – https://www.lung.org/quit-smoking/helping-teens-quit/vape-free-schools

[22] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8629945/

[23] – https://www.odu.edu/pediatrics/research-divisions/community-health–research/avert

Video Section

Check out our extensive video library (see channel for our latest videos)

Recent Articles