Tranexamic Acid in Non-Trauma Cases The Hidden Risks You Should Know

Introduction

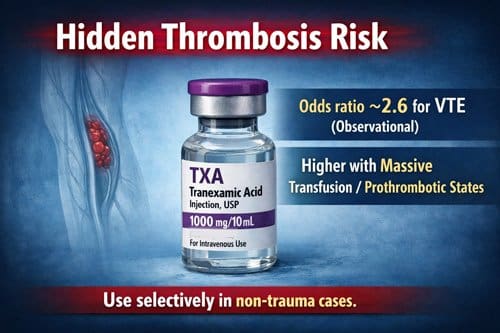

Tranexamic acid is a synthetic antifibrinolytic agent widely used to reduce bleeding by inhibiting plasminogen activation and fibrin degradation. Its efficacy in trauma related hemorrhage has led to broad acceptance across emergency medicine, surgery, and critical care. However, emerging evidence indicates that tranexamic acid administration may be associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolic events, prompting renewed scrutiny of its expanding use beyond traditional trauma settings. Observational data have identified tranexamic acid exposure as an independent risk factor for venous thromboembolism, with an odds ratio of 2.58 and a 95 percent confidence interval of 1.20 to 5.56, suggesting a clinically meaningful elevation in thrombotic risk.

Concerns regarding safety have been reinforced by findings from a cohort study involving 455 combat trauma patients, which reported an overall venous thromboembolic event rate of 15.6 percent. This incidence is markedly higher than the rates reported in earlier landmark trials such as CRASH 2 and the Military Application of Tranexamic Acid in Trauma Emergency Resuscitation study, which documented venous thromboembolism rates of approximately 1.8 percent and 4.0 percent, respectively. The discrepancy between these figures raises important questions regarding patient selection, dosing strategies, and evolving patterns of tranexamic acid administration in real world clinical practice.

Beyond incidence rates, trends in medication use among military physicians and first responders have revealed a shift toward improved adherence in terms of reduced missed doses, accompanied by a simultaneous increase in overadministration. This pattern suggests that while awareness of tranexamic acid benefits has improved, its use may be extending beyond evidence supported indications. Such practice variability highlights unresolved issues related to optimal dosing, timing of administration, and patient risk stratification. These concerns are particularly relevant as tranexamic acid is increasingly employed in non trauma contexts, including elective surgery, obstetrics, orthopedic procedures, and medical bleeding disorders.

The pharmacologic mechanism that underpins tranexamic acid’s effectiveness also contributes to its potential for harm. By inhibiting fibrinolysis, tranexamic acid stabilizes clot formation and reduces hemorrhage. However, in patients with underlying prothrombotic risk factors or in settings where coagulation is already activated, this same mechanism may predispose to pathological thrombosis. As a result, inappropriate or excessive use may increase the likelihood of deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or other thrombotic complications.

This article critically examines the evolving evidence surrounding tranexamic acid use outside of trauma care, with a focus on emerging safety signals and clinical decision making challenges. It reviews data from observational studies and clinical trials, explores patient populations at heightened risk for adverse events, and discusses strategies for optimizing dosing and indication selection. By balancing hemostatic benefit against thrombotic risk, this review aims to provide practical guidance for clinicians seeking to use tranexamic acid judiciously while minimizing preventable complications and improving overall patient outcomes.

Mechanism of Action and Pharmacokinetics of Tranexamic Acid

The molecular structure of tranexamic acid (TXA) forms the foundation for its potent antifibrinolytic properties in clinical medicine. This synthetic lysine derivative exerts its therapeutic effects through specific biochemical interactions within the coagulation cascade.

How tranexamic acid inhibits fibrinolysis

TXA functions as a competitive inhibitor of plasminogen activation by binding to lysine receptor sites on this molecule [1]. As a molecular analog of lysine, TXA effectively competes with fibrin for these binding sites, consequently preventing plasmin formation and subsequent fibrin degradation [1]. During normal hemostasis, plasminogen produced by the liver converts to plasmin through tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), initiating fibrinolysis [2]. Furthermore, TXA demonstrates approximately 10 times greater potency than aminocaproic acid, another antifibrinolytic agent [3]. This enhanced potency corresponds directly to TXA’s stronger binding affinity at both high and low-affinity plasminogen receptor sites [3].

Plasma half-life and renal excretion profile

Following oral administration, TXA reaches peak plasma concentration at 3 hours with an absolute bioavailability of approximately 45% [4]. In contrast, intravenous administration results in a triexponential decay pattern with an apparent elimination half-life of approximately 2 hours [3]. The mean terminal elimination half-life extends to approximately 11 hours [4]. Notably, TXA demonstrates minimal plasma protein binding—only about 3% at therapeutic levels [3].

Renal excretion constitutes the primary elimination pathway for TXA, with glomerular filtration accounting for over 95% of drug clearance as unchanged compound [4]. The overall renal clearance equals plasma clearance (110-116 mL/min) [3]. Additionally, excretion reaches approximately 90% at 24 hours post-intravenous administration [3]. The initial volume of distribution ranges from 9 to 12 liters [3].

Dose-response relationship in clot stabilization

Clinical evidence indicates TXA plasma concentrations between 10-15 mg/L provide near-maximal fibrinolysis inhibition, whereas concentrations between 5-10 mg/L deliver significant yet partial inhibition [5]. Specifically, TXA at 10 mg/L reduced anisoylated lys-plasminogen streptokinase activator complex-induced fibrinolysis by 80% [1]. Moreover, the concentration required for effective inhibition increases proportionally with tPA levels—by 0.004 mg/L for every 1 ng/mL of tPA used to stimulate fibrinolysis [5]. According to experimental models, the minimum effective concentration varies across patient populations, with 6.54 mg/L required in neonatal plasma versus 17.5 mg/L in adult plasma for complete fibrinolysis inhibition [5].

Non-Trauma Applications of Tranexamic Acid in Clinical Practice

Beyond its established role in trauma care, tranexamic acid (TXA) has gained traction across multiple medical specialties due to its efficacy in managing non-traumatic hemorrhage. Clinical applications continue to expand as practitioners recognize its utility in diverse settings.

Use in heavy menstrual bleeding and menorrhagia

TXA serves as a first-line treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB), reducing menstrual blood loss by 26-60% compared to baseline [6]. The FDA-approved oral dosage regimen consists of two 650 mg tablets three times daily for a maximum of 5 days per menstrual cycle [7]. Clinical studies demonstrate TXA’s superiority over placebo (26-50% vs 2-8% reduction) [6] and other conventional treatments, including NSAIDs and oral progestins. Remarkably, TXA normalizes menstrual blood volume in 56-100% of patients across various trials [6]. However, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system outperforms TXA, showing 83% reduction versus 47% with TXA after several months of treatment [6].

Application in dental surgery for hemophilia patients

Dental procedures pose significant bleeding risks for hemophilia patients. Subsequently, adjunctive therapy with TXA has become standard practice, typically administered pre- and post-extraction [8]. A Cochrane review revealed TXA significantly reduced postoperative bleeding in hemophilia patients undergoing dental extractions compared to placebo, with a combined risk difference of -0.57 (95% CI -0.76 to -0.37) [9]. Hence, both systemic and topical administration protocols demonstrate benefit, though standardized guidelines remain under development.

Role in orthopedic and cardiac surgeries

In cardiac surgery, TXA effectively reduces bleeding complications and transfusion requirements. Indeed, a randomized clinical trial involving 3,079 patients found high-dose TXA reduced allogeneic red blood cell transfusion rates to 21.8% versus 26.0% with low-dose regimens [10]. Nonetheless, practitioners must balance efficacy against potential complications, especially since seizures occurred in 1.0% of high-dose versus 0.4% of low-dose patients [10].

Off-label use in dermatology and cosmetic procedures

TXA has emerged as a promising agent in esthetic procedures, where its anti-inflammatory properties help minimize edema and ecchymosis [1]. Off-label applications include treatment of melasma [2], post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation [11], and as an adjunct in facial procedures. Among plastic surgeons, TXA is most commonly used in face-lifts (70.0%), neck lifts (62.0%), and rhinoplasty (50.0%), primarily administered as IV bolus (50.0%) or topically (47.0%) [1].

Emerging Risks in Non-Trauma Use of TXA

Growing clinical evidence raises concerns about tranexamic acid (TXA) applications beyond trauma settings. Recent data reveals several risks requiring careful consideration before administration.

Safety Concerns Associated with Tranexamic Acid Use

Increased incidence of thromboembolic events

Growing evidence suggests that tranexamic acid (TXA) may increase the risk of thromboembolic events in certain clinical settings. Military trauma studies have identified TXA administration as an independent risk factor for venous thromboembolism, with an odds ratio of 2.58 and a 95 percent confidence interval of 1.20 to 5.56 [12]. Combat casualty evaluations further reported an overall venous thromboembolism rate of 15.6 percent among patients receiving TXA, a figure markedly higher than previously reported rates in civilian populations [12].

The risk appears to be particularly pronounced in patients requiring massive transfusion. In this subgroup, venous thromboembolism rates reached 31.8 percent among those treated with TXA [12]. These findings suggest that in the context of severe trauma, extensive tissue injury, systemic inflammation, and aggressive transfusion practices, TXA may amplify an already prothrombotic physiological environment.

In contrast, large scale observational data from non trauma populations indicate a substantially lower absolute risk. An analysis of approximately 2.0 million women followed over 13.8 million person years demonstrated only one additional venous thromboembolism per 78,549 women using oral TXA for a five day course [13. This discrepancy underscores the importance of patient population, indication, and baseline thrombotic risk when interpreting TXA safety data.

Delayed administration and risk of clot propagation

The timing of TXA administration plays a critical role in determining both its efficacy and safety. While early administration is beneficial for hemorrhage control, delayed administration may contribute to adverse outcomes. Once active bleeding has subsided and fibrinolytic activity diminishes, TXA may promote excessive clot stabilization and propagation, effectively shifting the hemostatic balance toward a hypercoagulable state [14]. This phenomenon may increase the risk of pathological thrombosis, particularly in patients with existing clot formation or underlying prothrombotic risk factors. These findings highlight the necessity of adhering to evidence based timing recommendations when administering TXA.

Interaction with hormonal therapies and contraceptives

The combined use of TXA and hormonal contraceptives is associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic events. Both agents independently affect coagulation pathways, and their concurrent use produces an additive prothrombotic effect [3]. In response to this elevated risk, the United States Food and Drug Administration has contraindicated the use of TXA in women taking combined hormonal contraceptives, particularly among those who smoke, are obese, or are older than 35 years of age [7,15]. Careful medication reconciliation and individualized risk assessment are therefore essential prior to prescribing TXA in women of reproductive age.

Neurological adverse effects and seizure risk

TXA has also been associated with neurological adverse effects, most notably seizures. Mechanistically, TXA competitively inhibits gamma aminobutyric acid and glycine receptors in cortical neurons, leading to reduced inhibitory neurotransmission and increased neuronal excitability [16]. Clinical studies have demonstrated a dose dependent relationship between TXA exposure and seizure risk [17]. Reported cumulative seizure incidence rates reach approximately 2.7 percent in certain high risk populations [18].

Importantly, high dose TXA regimens have been associated with seizure rates that are approximately threefold higher than those observed with low dose protocols [19]. These findings are particularly relevant in settings such as cardiac surgery and major trauma, where higher TXA doses are commonly administered. Awareness of this risk has prompted increasing emphasis on dose optimization and neurological monitoring, especially in patients with pre existing neurological vulnerability.

Clinical Considerations and Safe Use Guidelines

Safe prescription of tranexamic acid (TXA) requires precise dosing strategies, thorough risk assessment, and vigilant monitoring. Proper clinical management varies based on patient factors and treatment indications.

Recommended tranexamic acid dosage by indication

For dental procedures in hemophilia patients, the FDA recommends 10 mg/kg IV immediately before extraction, followed by 10 mg/kg three to four times daily for 2-8 days [20]. With menorrhagia, patients typically receive 1300 mg orally three times daily for up to 5 days during menstruation [21]. Cardiac surgery patients may benefit from 10 g TXA administered over 20 minutes before sternotomy [22]. Renal dosing adjustments are mandatory as 95% of TXA undergoes renal excretion [21].

Patient screening for thrombotic risk factors

Clinicians must evaluate patients for contraindications, primarily thrombotic risk factors. Key screening criteria include personal/family history of DVT, PE, stroke, or hypercoagulable states [23]. For melasma treatment, routine coagulation studies are unnecessary [23]. TXA remains contraindicated in patients with active intravascular clotting, subarachnoid hemorrhage, or thromboembolic disease [21].

Monitoring protocols for long-term use

Long-term TXA administration warrants regular assessment via adverse event monitoring, physical examinations, vital sign checks, laboratory testing, and ophthalmologic examinations [24]. After several months, thromboembolic risks remain low in properly screened patients [25].

Alternatives to TXA in high-risk patients

For patients with contraindications, alternatives should be considered based on clinical context. Firstly, aminocaproic acid offers antifibrinolytic properties at lower potency [4]. Secondly, local hemostatic agents provide alternatives for minor procedures [26].

Conclusion

Tranexamic acid continues to demonstrate utility across multiple clinical specialties beyond its established role in trauma care. Nevertheless, practitioners must carefully weigh its hemostatic benefits against the emerging thromboembolic risks. Recent evidence underscores TXA administration as an independent risk factor for venous thromboembolic events, particularly in certain patient populations and with specific dosing regimens. The odds ratio of 2.58 for VTE development demands attention from clinicians considering this intervention.

Patient selection therefore becomes crucial when prescribing TXA for non-trauma indications. Menorrhagia treatment, dental procedures in hemophilia patients, and perioperative management during cardiac and orthopedic surgeries all show promising outcomes, albeit with varying degrees of evidence quality. Consequently, thorough screening for thrombotic risk factors must precede any TXA administration.

Timing also plays a pivotal role in TXA efficacy and safety profiles. Early administration typically yields optimal results, while delayed use may potentially enhance clot propagation and create hypercoagulable states. Additionally, practitioners should remain vigilant about potential drug interactions, especially with hormonal contraceptives, as these combinations may exponentially increase thromboembolic risk.

Pharmacokinetic considerations further complicate TXA prescribing patterns. The drug’s plasma half-life, renal excretion profile, and dose-response relationship all affect clinical outcomes. Thus, appropriate dosing adjustments become essential for patients with compromised renal function, given that 95% of TXA undergoes renal excretion.

Neurological complications, though less common than thrombotic events, still warrant consideration. TXA competitively inhibits GABA and glycine receptors in cortical neurons, occasionally resulting in seizures, particularly at higher doses. This risk appears dose-dependent, with high-dose regimens showing threefold higher seizure rates compared to low-dose protocols.

The expanding off-label applications in dermatology and cosmetic procedures, while promising, lack robust safety data comparable to established indications. Accordingly, clinicians should approach these newer applications with measured caution until more definitive evidence emerges.

Though TXA offers valuable therapeutic benefits across various clinical scenarios, its application demands meticulous risk assessment, appropriate patient selection, optimal timing, and vigilant monitoring. The balance between hemorrhage control and thrombotic risk remains delicate, requiring nuanced clinical judgment rather than algorithmic application. As research continues to evolve, physicians must stay abreast of emerging evidence to optimize patient outcomes while minimizing adverse events when utilizing this potent antifibrinolytic agent beyond traditional trauma settings.

Key Takeaways

Tranexamic acid has gained widespread adoption for hemorrhage control, particularly in trauma and surgical settings. While its antifibrinolytic properties offer clear benefits in reducing blood loss, emerging evidence suggests that its use outside well defined indications carries meaningful safety concerns. Increasing data highlight the importance of careful patient selection, appropriate timing, and close monitoring to mitigate potential harms associated with tranexamic acid administration.

Increased risk of thromboembolic events

Recent observational studies and post hoc analyses indicate that tranexamic acid independently increases the risk of venous thromboembolism, with reported odds ratios as high as 2.58. This elevated risk appears more pronounced in non trauma populations, where baseline coagulation abnormalities may be less apparent or insufficiently screened. These findings underscore the need to balance hemorrhage control benefits against the potential for thrombotic complications, particularly in patients with underlying prothrombotic risk profiles.

Importance of patient screening prior to use

Thorough pre treatment assessment is essential before prescribing tranexamic acid. Clinicians should evaluate individual thrombotic risk factors, including prior venous or arterial thrombosis, known thrombophilia, family history of clotting disorders, obesity, smoking status, and prolonged immobility. Tranexamic acid is contraindicated in patients with active intravascular clotting, and caution is warranted in those with conditions that predispose to hypercoagulability. Routine use without individualized risk assessment may expose patients to preventable adverse outcomes.

Timing of administration and clinical outcomes

The timing of tranexamic acid administration plays a critical role in both efficacy and safety. Early administration has been shown to provide optimal hemorrhage control by stabilizing clot formation and reducing fibrinolysis. In contrast, delayed administration may promote clot propagation and exacerbate hypercoagulable states, particularly once hemostasis has already been achieved. Evidence suggests that late use may shift the risk benefit balance toward harm, emphasizing the importance of early decision making in appropriate clinical contexts.

Interaction with hormonal therapies and contraceptives

The concurrent use of tranexamic acid and hormonal contraceptives significantly increases the risk of thromboembolic events. Both agents independently influence coagulation pathways, and their combined effect can substantially amplify clotting risk. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has contraindicated this combination, especially in women over the age of 35, smokers, and individuals with obesity. Clinicians should routinely inquire about hormonal therapy use and counsel patients accordingly before initiating tranexamic acid.

Neurological adverse effects and seizure risk

Tranexamic acid has been associated with neurological complications, most notably seizures. Mechanistically, tranexamic acid competitively inhibits gamma aminobutyric acid and glycine receptors in cortical neurons, leading to increased neuronal excitability. Clinical studies demonstrate a clear dose dependent relationship, with reported seizure incidence rates of approximately 2.7 percent overall. High dose regimens are associated with a threefold increase in seizure risk compared with lower dose protocols. Vigilant neurological monitoring is particularly important in patients receiving high doses or those with underlying neurologic vulnerability.

Clinical implications

The safe and effective use of tranexamic acid depends on judicious clinical decision making rather than routine application across all bleeding scenarios. Meticulous patient selection, early and appropriate timing of administration, avoidance of high risk drug combinations, and proactive monitoring for thrombotic and neurological complications are essential components of responsible tranexamic acid use. As evidence continues to evolve, clinicians must remain attentive to emerging safety data to ensure that the benefits of tranexamic acid consistently outweigh its risks in individual patients.

Frequently Asked Questions:

FAQs

Q1. What are the main risks associated with using tranexamic acid in non-trauma cases? The main risks include an increased incidence of thromboembolic events, potential for clot propagation with delayed administration, interactions with hormonal therapies, and neurological effects such as seizures.

Q2. How does tranexamic acid work to control bleeding? Tranexamic acid inhibits fibrinolysis by binding to lysine receptor sites on plasminogen, preventing its conversion to plasmin. This action stabilizes blood clots and reduces bleeding.

Q3. In which non-trauma medical situations is tranexamic acid commonly used? Tranexamic acid is frequently used for heavy menstrual bleeding, dental surgery in hemophilia patients, orthopedic and cardiac surgeries, and some dermatological and cosmetic procedures.

Q4. What precautions should be taken before administering tranexamic acid? Before administering tranexamic acid, healthcare providers should screen patients for thrombotic risk factors, consider timing of administration, adjust dosage for renal function, and avoid combining it with hormonal contraceptives.

Q5. Are there alternatives to tranexamic acid for patients at high risk of complications? Yes, alternatives include aminocaproic acid, which offers antifibrinolytic properties at lower potency, and local hemostatic agents for minor procedures. The choice depends on the specific clinical context and patient risk factors.

References:

[1] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9555985/

[2] – https://dermnetnz.org/topics/tranexamic-acid

[3] – https://www.drugs.com/drug-interactions/ethinyl-estradiol-with-tranexamic-acid-1039-0-2224-0.html

[4] – https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532909/

[5] – https://journals.lww.com/bloodcoagulation/fulltext/2019/01000/

what_concentration_of_tranexamic_acid_is_needed_to.1.aspx

[6] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3430088/

[7] – https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/tranexamic-acid-oral-route/description/drg-20073517

[8] – https://www.hemophilia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Nurses-dental-guidelines.pdf

[9] – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26704192/

[10] – https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2794565

[11] – https://jddonline.com/articles/the-use-of-tranexamic-acid-to-prevent-and-treat-post-inflammatory-hyperpigmentation-S1545961621P0344X

[12] – https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamasurgery/fullarticle/

2659483

[13] – https://www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(21)00162-0/fulltext

[14] – https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12959-022-00440-9

[15] – https://www.droracle.ai/articles/106240/what-is-the-interaction-between-tranexamic-acid-txa-and

[16] – https://www.nature.com/articles/srep13458

[17] – https://www.annalsthoracicsurgery.org/article/S0003-4975(11)01913-8/fulltext

[18] – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/

S1059131116000534

[19] – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26580862/

[20] – https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-provides-update-health-care-professionals-about-risk-inadvertent-intrathecal-spinal

[21] – https://www.drugs.com/dosage/tranexamic-acid.html

[22] – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10709819/

[23] – https://www.droracle.ai/articles/561177/what-blood-tests-are-required-before-starting-tranexamic-acid

[24] – https://www.fertstert.org/article/S0015-0282(10)01156-8/fulltext

[25] – https://consensus.app/search/long-term-oral-tranexamic-acid-risks/iYmA_twRSiazPb2BZB5yCw/

[26] – https://dph.sc.gov/sites/scdph/files/media/document/TXA Usage -forWEB.pdf

Video Section

Check out our extensive video library (see channel for our latest videos)

Recent Articles