Bite Therapy: CAR-T vs T-Cell Engagers – Which Saves More B-ALL Patients?

Introduction

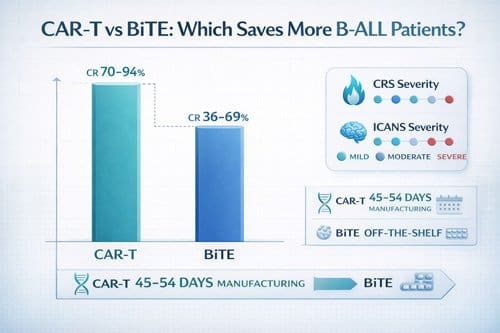

Bite therapy and CAR-T cell treatments have revolutionized the management of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), achieving remarkable remission rates. Second-generation CD19-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T cells achieve dramatic remission rates of 80% to 90% in children and young adults with multiply relapsed or refractory disease. In contrast, complete response rates for BiTE (Bispecific T-cell Engager) therapy range from 36% to 69% in clinical trials. Despite these impressive initial outcomes, more than half of patients relapse after CAR-T or T-cell engager therapy, with antigen escape or lineage switching accounting for approximately one-third of disease recurrences.

The administration methods of these therapies present distinct clinical considerations for practitioners. While bite therapy utilizes bispecific antibodies that can be delivered as “off-the-shelf” treatments, CAR-T requires personalized engineering of a patient’s own T cells. The bite therapy side effects profile differs from CAR-T toxicity patterns, though both can trigger cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity. Furthermore, bite therapy success rates show promising durability, with one study reporting an estimated 1-year overall survival rate of 71.9% in a cohort of patients. For patients previously treated with blinatumomab (a type of bite therapy), subsequent CAR-T treatment achieved an overall response rate of 76.6%. Although bite therapy vs CAR-T comparisons show different efficacy profiles, both approaches have secured their place in the treatment arsenal for relapsed/refractory B-ALL patients.

This article examines the evidence-based distinctions between these two immunotherapeutic approaches, exploring their mechanisms, clinical outcomes, resistance patterns, and practical considerations to help clinicians make informed decisions for their B-ALL patients.

Mechanism of Action: CAR-T vs T-Cell Engagers

T cells’ cancer-fighting capabilities form the foundation of both CAR-T and bite therapy approaches, yet they harness these immune soldiers through fundamentally different mechanisms. These distinct approaches create unique advantages and limitations that influence their clinical applications in B-ALL treatment.

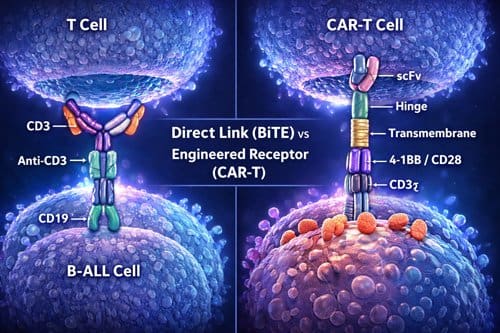

CAR-T: Engineered T cells with CD19 targeting

Chimeric antigen receptors fundamentally redefine how T cells recognize and destroy cancer cells. Unlike natural T cells, which require MHC-peptide presentation, CARs enable direct recognition of cell-surface antigens independent of MHC expression [1]. The CAR structure typically consists of an extracellular single-chain variable fragment (scFv) derived from an antibody, connected via a spacer and transmembrane domain to intracellular signaling domains [1]. This engineering creates a hybrid receptor combining an antibody’s targeting precision with a T cell’s killing capability.

The evolution of CAR designs has dramatically enhanced their efficacy. First-generation CARs used only the CD3ζ signaling domain, resulting in limited persistence and poor tumor control [2]. Second-generation CARs added co-stimulatory domains—primarily CD28 or 4-1BB—which significantly improved persistence, proliferation, and anti-tumor efficacy [1]. Third-generation CARs include two co-stimulatory domains for enhanced activation; fourth-generation designs add cytokine production capabilities; and fifth-generation approaches incorporate additional signaling pathways, such as JAK/STAT activation [3].

Currently approved CAR-T products for B-ALL primarily use second-generation designs. Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) employs a 4-1BB co-stimulatory domain, which contributes to its exceptional clinical efficacy with complete response rates ranging from 70% to 94% in acute lymphoblastic leukemia [1].

BiTEs: Bispecific antibodies linking CD3 and CD19

Bispecific T-cell engagers represent an entirely different approach to harnessing T-cell power. Rather than genetically modifying T cells, BiTEs are engineered antibodies with dual binding capabilities—one arm targets CD3 on T cells, and the other binds to CD19 on B-ALL cells [4]. This dual-targeting mechanism physically forces cancer and T cells into proximity, creating a cytolytic synapse that leads to tumor cell death [4].

BiTEs function as molecular bridges, enabling any T cell to become an anti-cancer effector regardless of its natural specificity. Unlike conventional antibodies, BiTEs lack an Fc region, which prevents activation of other immune cells, such as macrophages and natural killer cells [5]. This focused T-cell activation occurs without requiring costimulation, and evidence suggests BiTEs preferentially activate memory T cells [5].

Blinatumomab exemplifies this approach and demonstrates remarkable efficacy at very low doses—its maximum tolerated dose is 60 μg/m²/day, compared to 375 mg/m²/day for conventional antibodies like rituximab [5]. However, its small size leads to rapid renal clearance, necessitating continuous infusion to maintain therapeutic levels [4].

Immune synapse formation: Classical vs atypical

The immunological synapses formed by these therapies differ substantially in structure and dynamics. BiTEs induce a classical immune synapse similar to natural TCR-MHC interactions [1]. These synapses display a well-organized “bullseye” structure with concentric rings: the central supramolecular activation cluster (cSMAC) containing TCRs and CD28, surrounded by the peripheral SMAC with adhesion molecules, and the distal SMAC comprised of filamentous actin [4].

In contrast, CAR-T cells form atypical synapses that are smaller, less organized, and structurally distinct [6]. These synapses lack distinct LFA-1 adhesion rings and show disorganized Lck patterns rather than the clustered arrangement seen in classical synapses [6]. Notably, CAR-T synapses generate faster, stronger, but shorter-duration signaling compared to BiTE-induced synapses [6].

The functional consequences of these structural differences are significant. CAR-T cells exhibit accelerated recruitment of lytic granules to the synapse, faster target cell killing, and quicker detachment from dying tumor cells [6]. This rapid kill-and-move capability enables more efficient serial killing of multiple tumor cells. Conversely, BiTEs create more stable, longer-lasting synapses but may also help recruit bystander T cells to amplify the anti-tumor response [7].

These mechanistic differences help explain the distinct clinical profiles of these therapies and inform the ongoing development of next-generation approaches, including dual-targeting strategies such as CAR-STAb-T cells that combine both mechanisms [7].

Administration and Manufacturing Differences

The journey from laboratory to patient represents a crucial distinction between BiTE therapy and CAR-T cell treatments. Beyond their mechanistic differences, these therapeutic approaches follow fundamentally different paths in manufacturing, preparation, and administration—factors that directly impact clinical accessibility and patient outcomes.

How is BiTE therapy administered?

BiTE therapy utilizes engineered antibodies that can be manufactured in large quantities as standardized pharmaceutical products. Due to their remarkably short half-life, most BiTE therapies require continuous intravenous administration to maintain therapeutic levels. Blinatumomab exemplifies this approach, typically administered as a continuous IV infusion [3]. For many BiTE products, subcutaneous administration serves as an alternative delivery method, often used for weekly dosing schedules [8].

A strategic approach to BiTE administration involves ramp-up dosing—gradually increasing the dose to mitigate cytokine release syndrome and other immune-related side effects. This method has demonstrated a promising safety profile, with some studies reporting no higher-grade CRS events after the initial cycle [9]. The gradual increase in plasma cytokine levels achieved through this approach makes BiTE therapy suitable even for elderly patients over 80 years old [9].

Healthcare facilities implementing BiTE therapy typically establish standardized workflows for safe administration. These protocols include specialized staff training on managing potential complications, particularly cytokine release syndrome. Effective coordination between inpatient and outpatient settings ensures continuity of care throughout the treatment course [10].

CAR-T cell production: Autologous vs allogeneic

The production of autologous CAR-T cells follows a complex, multi-step process that begins with the patient’s own cells. This procedure includes:

- Leukapheresis to collect a sufficient quantity of the patient’s T cells

- Isolation of T cells from the leukapheresis product

- Genetic modification using viral vectors to express the CAR

- Expansion of modified cells to therapeutic quantities

- Lymphodepleting chemotherapy for the patient

- Reinfusion of the engineered cells [3]

Each step introduces potential points of failure, with manufacturing failure rates reaching approximately 7% in clinical trials [3]. Moreover, the entire process demands considerable time—the JULIET trial reported a median of 54 days from enrollment to infusion, with only 111 of 165 enrolled patients eventually receiving cells [3]. Similarly, the ELIANA trial showed a median of 45 days from enrollment to infusion, with only 75 of 92 enrolled patients receiving treatment [3].

Allogeneic CAR-T approaches aim to overcome these limitations by using T cells from healthy donors. This “off-the-shelf” model offers several advantages, including younger, healthier donor cells that may demonstrate superior persistence and activity [11]. Nevertheless, allogeneic approaches face unique challenges, primarily graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) and host-versus-graft rejection [12]. Novel engineering strategies address these issues through techniques such as equipping CAR-T cells with protective proteins, such as Nef, or eliminating the T-cell receptor to prevent GvHD [11].

Off-the-shelf vs personalized therapy

The contrast between immediate availability and personalized engineering creates distinctly different patient experiences. Off-the-shelf products like BiTE therapy allow patients to access treatment promptly upon diagnosis—a critical advantage for those with aggressive disease [13]. In the TOWER trial, 267 of 271 patients assigned to blinatumomab successfully received treatment, demonstrating exceptional accessibility [3].

Conversely, autologous CAR-T therapy requires sufficient peripheral blood counts for successful leukapheresis, potentially excluding patients with severe cytopenias [3]. Additionally, patients face the risk of disease progression during the manufacturing period—a particular concern with aggressive B-ALL [3].

For clinical practice, these differences translate to distinct hospitalization patterns and resource utilization. BiTE therapy can begin within days of the treatment decision, often following standardized administration protocols. CAR-T therapy, on the other hand, necessitates complex coordination between collection, manufacturing, and treatment centers, typically spanning several weeks [3].

Recent advances in allogeneic CAR-T technologies offer promise for combining personalization with off-the-shelf availability. Techniques utilizing donor selection based on specific immune characteristics and genetic modification to prevent rejection may eventually provide the benefits of both approaches [14]. Until then, the choice between immediate availability and fully personalized engineering remains a fundamental consideration in treatment selection.

Clinical Efficacy in B-ALL Patients

Direct comparisons between CAR-T and BiTE therapy reveal substantial differences in efficacy outcomes among B-ALL patients. When evaluating these therapies, clinicians must consider not only initial response rates but also MRD clearance and remission duration—factors that ultimately determine patient survival trajectories.

Complete remission rates: 70–94% (CAR-T) vs 36–69% (BiTE)

Evidence from clinical trials consistently shows higher complete remission (CR) rates with CAR-T cell therapy than with BiTE approaches. CAR-T cell therapy has achieved CR rates ranging from 70% to 94% in patients with relapsed/refractory B-ALL [5], setting a new benchmark for efficacy. In contrast, blinatumomab trials report more modest results, with objective response rates ranging from 36% to 69% [15][4].

The disparity becomes even more apparent in pediatric populations. The ELIANA trial, which led to FDA approval of tisagenlecleucel, showed that 81% of pediatric and young adult patients achieved complete remission by three months post-infusion [15]. Conversely, when blinatumomab was administered to 70 pediatric patients, only 39% achieved CR [15].

Meta-analyzes further confirm this efficacy gap. One comprehensive analysis found pooled CR rates of 86% for CAR-T cell therapy versus 48% for blinatumomab [16]. Accordingly, CAR-T cell therapy was associated with a higher likelihood of complete remission, regardless of adjustment for various subgroups [16].

MRD-negative conversion: Comparative data

Beyond the initial response, minimal residual disease (MRD) status is a critical predictor of long-term outcomes. Generally, CAR-T cell therapy demonstrates superior ability to achieve MRD-negative remission.

Among patients achieving complete remission with blinatumomab, 63% to 88% of adults attain MRD-negative status [15]. The picture changes dramatically for pediatric patients, where merely 20% become MRD-negative despite treatment [15]. In stark contrast, CAR-T therapy results in MRD-negative rates of 80% [16], with the vast majority of responders clearing residual disease.

Interestingly, pooled analyses across multiple studies confirm this pattern, with MRD-negative rates of 31% with blinatumomab versus 80% with CAR-T cell therapy [16]. The ability to completely eradicate detectable disease markedly influences subsequent treatment decisions, especially regarding potential consolidative stem cell transplantation.

Long-term survival: 1-year OS and RFS

Initial response rates ultimately matter only insofar as they translate into extended survival. Here again, CAR-T demonstrates considerable advantages over BiTE therapy.

Patients successfully treated with blinatumomab typically experience a shorter relapse-free survival (RFS) of 5.9 to 6.7 months, with a median overall survival (OS) of 6.1 to 7.1 months [15]. The two-year OS rate for blinatumomab patients reaches approximately 25% [16].

CAR-T therapy produces substantially more durable outcomes. Updates from the ELIANA trial revealed RFS rates of 80% at 6 months and 66% at both 12 and 18 months [15], with evidence of ongoing functional CAR-T activity through persistent B-cell aplasia. Comparative analyses show that CAR-T therapy is associated with significantly prolonged OS and RFS compared with blinatumomab, with 2-year OS of 55% versus 25% [16].

For patients who respond to initial therapy and proceed to allogeneic stem cell transplantation, outcomes improve considerably. CAR-T therapy appears more effective than blinatumomab for achieving CR and for successfully bridging to transplant [16]. When analyzing long-term data from pediatric trials, the three-year RFS for patients undergoing alloHSCT was 52%, compared with 48% for non-transplanted patients [17], suggesting that a subset of pediatric patients can maintain durable remissions without consolidative transplantation.

The clinical efficacy differences between these therapeutic approaches reflect their distinct mechanisms of action and administration methods, with CAR-T cell therapy demonstrating superior response rates, MRD clearance, and survival outcomes across most patient populations.

Side Effects and Safety Profiles

The therapeutic benefits of CAR-T and BiTE approaches must be weighed against their distinctive safety profiles. Although both therapies can trigger immune-mediated toxicities, their frequency, timing, and severity differ substantially—considerations that often influence treatment selection for B-ALL patients.

Cytokine Release Syndrome: Grade 1–4 incidence

Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) occurs more frequently with CAR-T cell therapy compared to BiTE approaches. CAR-T therapy induces CRS in approximately 80-90% of patients, while BiTE therapy triggers it in 55-60% of cases [2]. The severity gradient also differs substantially between these approaches, with grade ≥3 CRS occurring in 7-14% of CAR-T recipients, yet in only 1-3% of patients receiving BiTE therapy [2].

Timing patterns reflect the underlying biological mechanisms. BiTE-induced CRS typically manifests within hours to days of administration, whereas CAR-T-associated CRS often emerges later—usually 4-10 days post-infusion [7]. This delayed onset with CAR-T cells is due to their need to proliferate before achieving sufficient cytokine levels. Interestingly, CRS duration tends to be longer with CAR-T therapy (median 5 days) compared to BiTE approaches (median 2 days) [18].

Management strategies vary by severity: grade 1 CRS typically receives supportive care, while higher grades require tocilizumab and corticosteroids. Tocilizumab administration is notably more common with CAR-T therapy (44% of patients) than with BiTE therapy (25%) [18].

Neurotoxicity and ICANS: Frequency and severity

Immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) represents a potentially life-threatening complication occurring in 20-60% of CAR-T recipients [19]. In contrast, BiTE therapy produces substantially lower rates of neurotoxicity, typically 3-8% depending on the specific agent [20]. Furthermore, the severity profile differs dramatically—high-grade ICANS occurs in 10-30% of CAR-T patients but remains rare with BiTE therapy [21].

ICANS typically begins approximately 5 days after CAR-T infusion, sometimes concurrently with or shortly following CRS [19]. Early symptoms include:

- Hesitancy of speech and deterioration in handwriting

- Mild tremor and confusion

- Word-finding difficulties and impaired fine motor skills

These initial manifestations may progress to more severe complications such as aphasia, agitation, seizures, and occasionally cerebral edema [19]. Consequently, close monitoring using the 10-point Immune Effector Cell Encephalopathy (ICE) score is essential for early detection and intervention.

BiTE therapy side effects vs CAR-T toxicity

Beyond CRS and ICANS, these therapies exhibit fundamentally different safety profiles. Hematological toxicities occur with both approaches yet present distinct patterns. Neutropenia appears more frequently with BiTE therapy (20.2%) than with CAR-T (11.6%) [1]. Primarily, this reflects the continuous administration of BiTEs versus the one-time infusion of CAR-T cells.

Cardiac, renal, and hepatic complications occur more frequently following CAR-T therapy. Cardiotoxicity rates reach 8.15% with CAR-T versus 3.4% with BiTEs, while hepatotoxicity occurs in 2.2% versus 1.0% of patients, respectively [1]. Acute kidney injury follows a similar pattern (7.3% vs. 4.8%).

The risk-benefit analysis between these therapies often hinges on practical considerations. BiTE therapy’s step-up dosing strategy and shorter duration of toxicity offer advantages for outpatient management. Essentially, the ability to interrupt treatment upon the development of toxicity provides an important safety mechanism unavailable with CAR-T therapy, where the engineered cells persist independently [6].

Impact of Prior Blinatumomab on CAR-T Outcomes

Sequential administration of CD19-targeted therapies raises critical questions regarding their cumulative efficacy in B-ALL treatment. As both therapies target the same antigen, clinicians must understand how prior bite therapy affects subsequent CAR-T outcomes.

Response rates in blinatumomab-exposed vs naive patients

The relationship between prior blinatumomab exposure and CAR-T efficacy is nuanced. Among patients receiving CD19-CAR therapy, those previously treated with blinatumomab show varying outcomes based on their initial response. Blinatumomab non-responders achieve substantially lower complete remission rates to CD19-CAR (64.5%) compared to blinatumomab responders (92.9%) or blinatumomab-naive patients (93.5%) [22].

This pattern extends to survival metrics as well. Following CD19-CAR therapy, blinatumomab non-responders experience markedly worse 6-month event-free survival (27.3%) versus blinatumomab responders (66.9%) or blinatumomab-naive patients (72.6%) [22]. Indeed, the cumulative incidence of relapse at 6 months reflects this gradient: 52.4% in non-responders, 26.2% in responders, and 18.6% in blinatumomab-naive patients [23].

A multicenter analysis of pediatric patients found that prior exposure to blinatumomab alone did not predict worse outcomes. Instead, failure to respond to blinatumomab served as a stronger predictor of subsequent CAR-T resistance [24].

CD19 downregulation and antigen escape

Reduced CD19 expression represents one potential mechanism for diminished CAR-T efficacy following blinatumomab. CD19-dim or partial expression occurs more frequently in blinatumomab-exposed patients (13.3%) than in blinatumomab-naive patients (6.5%) [22]. This altered expression pattern correlates with inferior event-free and relapse-free survival.

For patients who retain robust CD19 expression after blinatumomab, other factors beyond simple antigen loss may influence outcomes. In fact, even among patients with confirmed CD19-positive disease before CAR infusion, complete remission rates were lower in blinatumomab-exposed patients (82.5%) than in blinatumomab-naive patients (92.9%) [22].

Several mechanisms may explain these observations:

- Enrichment of pre-existing CD19-negative tumor clones

- Alternative CD19 splicing creates unrecognizable isoforms

- CD19 redistribution or epitope masking

- Underlying T-cell dysfunction unrelated to antigen expression [25]

The hypothesis that high-disease-burden patients harbor undetectable CD19-negative populations that emerge after clearance of CD19-positive disease is supported by recent single-cell analyses [10].

Timing between therapies and sequencing strategies

The optimal interval between discontinuation of blinatumomab and CAR-T infusion remains under investigation. Currently available data show a median time of 131 days (range 39-983 days) between the most recent blinatumomab administration and CAR-T infusion [22]. This timeframe allows for:

- Recovery of CD19+ cells, which is necessary for in vivo CAR-T activation and expansion [26]

- Clearance of residual blinatumomab (half-life ~16 days) [27]

- Restoration of normal T-cell function following potential bite therapy-induced exhaustion [26]

In patients with low CD19 expression after blinatumomab, the risk of antigen-negative relapse after CD19-CAR therapy is particularly high [23]. Thus, pre-CAR assessment of CD19 expression can guide clinical decision-making regarding the timing of subsequent therapy.

Given these findings, blinatumomab exposure or non-response should not be considered an absolute contraindication for CAR-T therapy [24]. Rather, clinicians should consider the response to prior bite therapy as an important stratification factor when predicting outcomes and determining whether additional post-CAR consolidation is necessary.

Resistance Mechanisms and Relapse Patterns

Disease relapse after initial response represents a major challenge with both CAR-T and bite therapy approaches. Nearly 50% of B-ALL patients experience relapse within 12 months following anti-CD19 or anti-CD22 CAR-T cell therapy [28]. Understanding these resistance patterns helps clinicians anticipate challenges and develop more effective sequential treatment strategies.

CD19-negative relapse: Splice variants and escape

Antigen loss or modification is the primary mechanism of treatment failure, occurring in 20-30% of patients receiving either CD19 CAR-T cells or blinatumomab [15]. Multiple biological pathways contribute to this phenomenon. Alternative splicing represents a sophisticated escape mechanism in which exons are cleaved from primary mRNA transcripts and rejoined in different combinations. Specifically, skipping exon 2 in CD19 generates truncated protein variants that retain some CD19 functions but lack the epitope recognized by CAR-T cells [14].

Frameshift mutations present another path to resistance. These genetic alterations in exon 2 of CD19 prevent normal protein expression without eliminating CD19’s functional role in leukemic cells [14]. Interestingly, some patients develop hemizygous deletions spanning the entire CD19 locus [29].

Beyond genetic alterations, trogocytosis enables the transfer of target antigens from tumor cells to T cells. During this process, CAR-T cells extract CD19 from leukemic cells, subsequently reducing both CD19 density on tumor surfaces and CAR expression on T cells [30]. This leads to diminished recognition and potential T-cell fratricide.

For CD22-targeted therapies, simply decreasing antigen density proves sufficient to enable escape without complete antigen loss [28]. This quantitative reduction in surface expression explains why some patients relapse despite maintaining CD22 positivity.

T-cell exhaustion and early CAR loss

Persistent antigen stimulation frequently leads to T-cell exhaustion—a state characterized by diminished proliferative capacity and impaired effector function [31]. Exhausted T cells typically express elevated levels of inhibitory checkpoint molecules such as PD-1, TIM-3, TOX, and CD39 [32].

The persistence of CAR-T cells is crucial for maintaining remission. Early B-cell recovery (within 6 months of infusion) strongly correlates with increased relapse risk [33]. Patients who relapse with CD19-positive disease typically demonstrate poor CAR-T expansion relative to their pre-treatment tumor burden [34].

Immune-mediated rejection may limit CAR-T persistence in some cases. Studies show CAR-specific T-cell responses detected in patients receiving repeat CAR-T infusions, suggesting host immune recognition of CAR components [28]. Additionally, intrinsic factors like CAR design, starting T-cell phenotype, and manufacturing methodology influence persistence [33].

Dual targeting to prevent relapse

Multi-antigen targeting strategies increasingly demonstrate promise for overcoming antigen escape. In a phase I trial investigating CD19/CD22 dual-targeting CAR-T cells, 100% of patients with relapsed/refractory B-ALL achieved MRD-negative complete remission [13]. Similarly, tandem CD19/CD22 CAR-T therapy showed superior complete response rates (98.0%) compared with single CD19-targeting (83.0%) [11].

Various dual-targeting approaches exist, including:

- Coadministration of separate single-target CAR-T products

- Bicistronic vectors expressing two CARs

- Cotransduction with multiple vectors

- Tandem CARs with two binding domains

Importantly, no antigen-negative escapes were reported with dual-targeting approaches at a median follow-up of 8.7 months in one study [12]. The 12-month overall survival rate reached 75% with dual targeting, and the event-free survival rate was 60% [12].

Research into CAR-STAb-T cells, which secrete soluble anti-CD19 BiTEs in addition to expressing a CAR, shows promise for preventing resistance. In preclinical studies, these cells eliminated leukemia even at extremely low effector-to-target ratios (1:32), outperforming both conventional CAR-T cells and exogenously administered blinatumomab [30].

Dual-Targeting and Next-Gen Therapies

Innovation in dual-targeting approaches for B-ALL represents a pivotal advancement beyond single-antigen strategies. These next-generation therapies aim to overcome the challenge of antigen escape, which limits the durability of both CAR-T and bite therapy treatments.

CD19/CD22 CARs vs CAR-STAb-T cells

Traditional multi-targeting CAR approaches have evolved through various configurations, including pooling separate CAR vectors, creating bicistronic vectors that express two different CARs, or designing tandem CARs with two binding domains in a single construct [35]. Yet, despite promising results, these approaches still face limitations when tumor heterogeneity leads to simultaneous downregulation of multiple targets [35].

A groundbreaking alternative merges the strengths of both CAR-T and bite technologies—CAR-STAb-T cells (Secreting T cell-redirecting Antibodies). These innovative cells simultaneously express a CAR targeting one antigen (typically CD22) while secreting bispecific antibodies targeting another (usually CD19) [3]. This dual-mechanism approach combines membrane-anchored CAR signaling with soluble BiTE recruitment, creating a synergistic strategy that maximizes both the efficacy and durability of clinical responses [3].

Recruiting bystander T cells via secreted BiTEs

Perhaps the most compelling advantage of CAR-STAb-T cells lies in their ability to engage untransduced bystander T cells present at tumor sites [8]. Unlike conventional CAR-T cells, which can activate only the engineered cells themselves, secreted BiTEs can recruit the entire pool of T lymphocytes—both engineered and unmodified [8].

This recruitment capability allows CAR-STAb-T cells to maintain high cytotoxicity even at extraordinarily low effector-to-target ratios. Studies demonstrate that CAR-STAb-T cells can achieve over 80% cytotoxicity at an effector-to-target ratio of 1:500, whereas traditional dual CARs lose effectiveness at ratios below 1:10 [3]. Hence, fewer infused cells can generate stronger anti-tumor responses, thereby reducing manufacturing requirements and potentially decreasing toxicity.

Preclinical and early clinical trial results

In head-to-head comparisons, CAR-STAb-T cells have demonstrated superior cytotoxic activity compared to dual-targeting CAR-T cells, particularly in B-ALL models with heterogeneous antigen expression [3]. Thereby, when tested against leukemia cells with mixed CD19-positive and CD19-negative populations, CAR-STAb-T cells induced more potent and faster cytotoxic responses than tandem CAR approaches in both short and long-term assays [3].

In vivo studies using patient-derived xenograft models under T cell-limiting conditions showed that CAR-STAb-T cells maintained tighter control of tumor progression than conventional dual-targeting approaches [9]. Currently, small numbers of transduced CAR-STAb-T cells have proven sufficient to redirect non-transduced bystander T cells specifically and efficiently against leukemia cells [9].

Beyond B-ALL, this secretion-based approach has shown promise in solid tumors, where locally secreted BiTEs complement CAR-T cells against antigen-heterogeneous tumors [36]. Recently, early clinical data from glioblastoma trials using a similar approach (CAR-TEAM cells) demonstrated remarkable tumor regression in patients, including a 60.7% decrease maintained for over six months in one case [37].

Cost, Accessibility, and Practical Considerations

Financial considerations fundamentally shape treatment decisions alongside efficacy and safety profiles. The economic impact of these therapies extends beyond initial price tags to encompass broader healthcare resource utilization.

Cost of CAR-T vs BiTE therapy

CAR-T therapy costs substantially more, ranging from $500,000 to $1,000,000 per treatment [38]. Real-world comparisons reveal CAR-T’s average total care cost ($702,000) exceeds BiTE therapy ($372,000) by approximately $330,000 [39]. Drug expenses account for 74% of CAR-T’s total cost ($521,000), compared with 49% for BiTE therapy ($183,000) [39].

Yet cost-effectiveness analyzes tell a more nuanced story. Quality-adjusted life-years favor CAR-T (11.26) over blinatumomab (2.25), potentially justifying higher initial investment [40]. For practitioners, this balance between immediate expense and long-term outcomes remains a critical consideration.

Hospitalization and monitoring needs

The monitoring requirements differ dramatically between approaches. CAR-T typically demands extended hospitalization with median inpatient stays of 6-10 days [41]. In contrast, BiTE therapy often transitions to outpatient administration after initial observation.

Adverse event management drives this disparity—52% of CAR-T patients experience complications requiring intervention, compared with 23% of BiTE patients [39]. The financial implications of these events are noteworthy: $9,000 per CAR-T patient compared to under $500 for BiTE recipients [39].

Insurance and manufacturing delays

Insurance coverage presents ongoing challenges. While Medicare covers CAR-T therapy, Medicaid coverage varies by state [38]. Private insurers have inconsistent policies that require extensive prior authorization.

Manufacturing bottlenecks create profound access barriers. The JULIET trial reported a median interval of 54 days from enrollment to infusion, with only 111 of 165 enrolled patients ultimately receiving CAR-T cells [6]. Approximately 20% of eligible patients die before receiving treatment due to waitlists [42].

Conclusion

The comparative analysis of CAR-T cell therapy and BiTE approaches reveals distinct profiles that shape clinical decision-making for B-ALL patients. CAR-T cells demonstrate superior complete remission rates (70-94%) compared with BiTE therapy (36-69%), along with higher rates of MRD-negative conversion and improved long-term survival. Nevertheless, these efficacy advantages come with considerable trade-offs.

CAR-T therapy presents more frequent and severe cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity, whereas BiTE therapy offers the safety advantage of immediate discontinuation if toxicity develops. Furthermore, the practical implications of these therapies extend beyond clinical outcomes. CAR-T requires complex manufacturing processes with waiting periods that can exceed 50 days, during which the patient’s disease may progress. Conversely, BiTE therapy provides immediate “off-the-shelf” availability, albeit with the inconvenience of continuous administration.

Financially, the disparity remains substantial. CAR-T’s average total care cost ($702,000) exceeds BiTE therapy ($372,000) by approximately $330,000, though improved quality-adjusted life years may justify this premium for appropriate candidates. Patient selection thus becomes paramount when navigating these options.

Prior exposure to blinatumomab influences subsequent CAR-T outcomes, particularly among non-responders who demonstrate markedly lower complete remission rates (64.5%) compared to blinatumomab-naive patients (93.5%). This finding underscores the value of response history in predicting treatment success and potentially guiding sequencing decisions.

Resistance mechanisms, especially CD19-negative relapse and T-cell exhaustion, continue to challenge both therapeutic approaches. Accordingly, dual-targeting strategies have emerged as promising solutions. CAR-STAb-T cells represent a particularly innovative advancement, combining membrane-anchored CAR signaling with the ability to recruit soluble BiTEs. This dual-mechanism approach harnesses bystander T cells and maintains efficacy even at extraordinarily low effector-to-target ratios.

Though CAR-T and BiTE therapies have transformed B-ALL treatment, neither represents a perfect solution. The ideal approach likely depends on individual patient factors, including disease burden, prior therapy exposure, comorbidities, and practical considerations such as insurance coverage and proximity to specialized treatment centers.

The future appears increasingly focused on combination strategies that leverage the complementary strengths of these approaches while minimizing their respective limitations. Until then, clinicians must carefully weigh efficacy, safety, logistical, and financial considerations when selecting between these revolutionary immunotherapeutic modalities for their B-ALL patients.

Key Takeaways

CAR-T and BiTE therapies represent revolutionary immunotherapies for B-ALL, each with distinct advantages that guide optimal patient selection and treatment sequencing.

- CAR-T delivers superior efficacy: Complete remission rates of 70-94% versus 36-69% for BiTE therapy, with better MRD clearance and longer survival outcomes.

- BiTE offers immediate accessibility: Off-the-shelf availability eliminates manufacturing delays, while CAR-T requires 45-54 days, with 20% of patients dying before treatment.

- Safety profiles differ significantly: CAR-T causes more severe cytokine release syndrome (7-14% grade ≥3) and neurotoxicity, while BiTE allows immediate discontinuation if toxicity develops.

- Prior blinatumomab exposure matters: Non-responders to BiTE therapy show reduced CAR-T success rates (64.5% vs 93.5% in naive patients), affecting treatment sequencing decisions.

- Dual-targeting approaches prevent resistance: CAR-STAb-T cells combining CAR and BiTE mechanisms show promise for overcoming antigen escape that limits single-target therapies.

The choice between these therapies ultimately depends on individual patient factors, including disease urgency, prior treatment history, comorbidities, and practical considerations such as insurance coverage and proximity to treatment centers. Future combination strategies may leverage both approaches’ complementary strengths while minimizing their respective limitations.

Frequently Asked Questions:

FAQs

Q1. What are the main differences between CAR-T and BiTE therapies for B-ALL? CAR-T therapy uses engineered T cells to target cancer cells, while BiTE therapy uses bispecific antibodies to link T cells and cancer cells. CAR-T generally shows higher complete remission rates (70-94%) than BiTE therapy (36-69%), but is associated with more severe side effects and longer manufacturing times.

Q2. How do the safety profiles of CAR-T and BiTE therapies compare? CAR-T therapy tends to cause more severe cytokine release syndrome (7-14% grade ≥3) and neurotoxicity. BiTE therapy has a milder side effect profile and allows for immediate discontinuation if toxicity develops, offering a safety advantage in some cases.

Q3. Does prior BiTE therapy affect the success of subsequent CAR-T treatment? Yes, prior BiTE therapy can impact CAR-T outcomes. Patients who did not respond to BiTE therapy have lower complete remission rates with CAR-T (64.5%) than BiTE-naive patients (93.5%). This information is important for treatment sequencing decisions.

Q4. What are dual-targeting approaches in B-ALL treatment? Dual-targeting approaches, such as CAR-STAb-T cells, combine multiple mechanisms to overcome resistance. These innovative therapies target two different antigens simultaneously, helping to prevent antigen escape and potentially improving treatment durability.

Q5. How do the costs and accessibility of CAR-T and BiTE therapies differ? CAR-T therapy is significantly more expensive, with average total care costs around $702,000 compared to $372,000 for BiTE therapy. BiTE therapy offers immediate “off-the-shelf” availability, while CAR-T requires a complex manufacturing process that can take 45-54 days, during which some patients may experience disease progression.

References:

[2] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11574411/

[3] – https://jitc.bmj.com/content/13/4/e009048

[4] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11969774/

[5] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8154758/

[6] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7839370/

[8] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11109416/

[9] – https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2024.42.16_suppl.2550

[10] – https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.21.01405

[11] – https://www.nature.com/articles/s41408-023-00819-5

[14] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4670800/

[15] – https://ashpublications.org/bloodadvances/article/5/2/602/

475006/CAR-T-cells-better-than-BiTEs

[16] – https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/

17474086.2023.2298732

[18] – https://ascpt.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cpt.3223

[19] – https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK584157/

[21] https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neurology/articles/

10.3389/fneur.2024.1392831/full

[22] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8937010/

[24] – https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ejh.14132

[25] – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/

S0753332224011363

[26] – https://haematologica.org/article/view/haematol.2023.283780

[27] – https://aacrjournals.org/clincancerres/article/30/14/2895/746332/

Sequencing-of-Anti-CD19-Therapies-in-the

[28] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8214555/

[29] – https://aacrjournals.org/cancerdiscovery/article-abstract/5/12/1282/5329

[30] – https://aacrjournals.org/cancerimmunolres/article/10/4/498/689536/

Overcoming-CAR-Mediated-CD19-Downmodulation-and

[31] – https://www.thelancet.com/journals/ebiom/article/PIIS2352-3964(22)00125-6/fulltext

[32] – https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/

fimmu.2025.1531145/full

[33] – https://ashpublications.org/bloodadvances/article/9/4/704/534321/

Dual-targeting-CAR-T-cells-for-B-cell-acute

[34] – https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/138/12/1081/476038/

CD19-target-evasion-as-a-mechanism-of-relapse-in

[35] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9262817/

[36] – https://www.cell.com/cell-reports-medicine/fulltext/S2666-3791(25)00426-4

[38] – https://www.webmd.com/cancer/lymphoma/features/navigate-finances-car-t-cell-therapy

[40] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7839358/

[42] – https://www.advisory.com/daily-briefing/2022/06/03/car-t-therapy

Video Section

Check out our extensive video library (see channel for our latest videos)

Recent Articles