The Role of Plant-Based Diets in Slowing Chronic Kidney Disease Progression: An Analytical Review

Abstract

Background:

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects more than 10% of the global population and is increasingly recognized as a critical public health challenge. Its rising prevalence is largely attributed to the growing burden of diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and dietary risk factors. Traditional dietary management of CKD has focused on protein restriction and limiting intake of minerals such as sodium, phosphorus, and potassium. However, a growing body of evidence suggests that plant-based dietary patterns may offer superior nephroprotective effects compared with conventional approaches.

Purpose:

This review synthesizes and critically evaluates current evidence on the role of plant-based diets in the management of CKD. Specifically, it examines proposed mechanisms of benefit, clinical outcomes, safety considerations, and the potential of these diets to delay disease progression and reduce associated complications.

Methods:

A comprehensive review of systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, and mechanistic studies published between 2018 and 2025 was conducted. Studies were selected based on their focus on plant-based dietary interventions in CKD populations, with outcomes assessed for effects on kidney function, disease progression, all-cause mortality, and CKD-related complications such as metabolic acidosis, hyperphosphatemia, and uremic toxin accumulation.

Results:

Evidence from a meta-analysis including 121,927 participants demonstrated that higher adherence to plant-based dietary patterns was associated with a 26% reduction in the risk of incident CKD. A dose–response relationship was observed, with greater plant food intake linked to progressively lower CKD risk and slower disease progression [1]. Among patients with established CKD, adherence to overall plant-based diets was associated with a 26% reduction in all-cause mortality, while adherence to healthy plant-based diets was associated with a 21% reduction. In contrast, consumption of unhealthy plant-based diets, characterized by refined grains and processed foods, was associated with increased risks of CKD progression and mortality [2].

Mechanistic studies suggest multiple pathways through which plant-based diets exert renoprotective effects. These include reduced dietary acid load, decreased intake of bioavailable phosphorus and potassium, increased fiber consumption, and favorable modulation of the gut microbiota. Improved gut health reduces the generation of uremic toxins, while plant-derived nutrients enhance anti-inflammatory and antioxidant responses. Collectively, these mechanisms may slow nephron injury and preserve residual kidney function.

Conclusions:

Current evidence supports the potential benefits of plant-based diets as part of an integrative approach to CKD management. Concerns remain regarding the risks of hyperkalemia and inadequate protein intake, yet emerging studies suggest that these risks are often manageable and may be overstated when diets are carefully designed and monitored. Plant-based diets offer multiple complementary mechanisms for slowing CKD progression, reducing complications, and improving long-term outcomes. Nonetheless, high-quality randomized controlled trials are needed to strengthen causal inference and inform evidence-based dietary guidelines for CKD care.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, plant-based diet, vegetarian diet, nephrology, disease progression, uremic toxins, dietary protein, kidney function

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) represents one of the most pressing global health challenges of the 21st century. Affecting more than 10% of the general population worldwide, CKD incidence continues to rise due to increasing prevalence of risk factors including obesity, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus [3] [4]. The progressive nature of CKD, characterized by declining glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and increasing proteinuria, leads to notably emphasized protein restriction, phosphorus limitation, and potassium avoidance, but these approaches have shown limited success in halting disease progression and may inadvertently restrict foods with potential nephroprotective properties.

In recent years, a growing body of evidence has emerged on the benefits of plant-based diets for the prevention and treatment of lifestyle diseases [5] [6], including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and hypertension—conditions closely associated with CKD development and progression. Improving the nutrient quality of foods consumed by patients by including a higher proportion of plant-based foods while reducing total and animal protein intake may reduce the need for or complement nephroprotective medications, improve kidney disease complications, and perhaps favorably affect disease progression and patient survival [7].

Plant-based diets, broadly defined as dietary patterns that emphasize foods derived from plants while reducing or eliminating animal products, present a paradigm shift in CKD management. These diets, which may include small to moderate amounts of animal foods, have received increasing interest because they have been associated with favorable effects on health and appear to protect against the development and progression of CKD [8]. However, the application of plant-based approaches in CKD remains controversial, with persistent concerns about protein adequacy, hyperkalemia risk, and practical implementation challenges.

This analytical review aims to critically examine the current evidence regarding plant-based diets in CKD management, evaluating both potential benefits and limitations. Specifically, we will explore the mechanisms by which plant-based diets may influence CKD progression, analyze clinical outcomes from recent studies, address safety concerns, and discuss practical implementation considerations. By synthesizing the available evidence, this review seeks to provide a balanced perspective on the role of plant-based dietary approaches in contemporary CKD management and identify areas requiring further research.

The growing interest in plant-based approaches for CKD management reflects broader recognition that dietary interventions may offer more sophisticated therapeutic benefits than traditional restriction-based approaches. Current evidence suggests that plant-based diets should be recommended for both primary and secondary prevention of CKD, with concerns of hyperkalemia and protein inadequacy potentially being outdated and unsupported by the current body of literature [9]. Understanding the evidence base for these claims is essential for clinicians, researchers, and patients navigating the evolving landscape of CKD dietary management.

Defining Plant-Based Diets in the Context of CKD

Plant-based diets encompass a spectrum of dietary patterns that emphasize foods derived from plants while varying in their inclusion of animal products. While no formal definition of a “plant-based diet” exists, this term is commonly used to refer to dietary patterns that promote plant foods such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and plant proteins such as nuts, seeds, and legumes. Plant-based diets do not necessarily indicate complete avoidance of animal products [10].

The major categories of plant-based diets relevant to CKD management include:

Whole Food Plant-Based (WFPB) Diets

These diets emphasize fresh, minimally processed or refined plant-based foods and limit animal products [11], focusing on nutrient density and avoiding processed foods that may contain harmful additives such as phosphorus-based preservatives.

Vegetarian Diets

These include lacto-ovo vegetarian (including dairy and eggs), lacto-vegetarian (dairy only), ovo-vegetarian (eggs only), and pescatarian (including fish) variants. Each type offers different nutritional profiles and practical considerations for CKD patients [12].

Vegan Diets

Complete elimination of animal products, requiring careful attention to potential nutrient deficiencies such as vitamin B12, vitamin D, and specific amino acid profiles.

Plant-Dominant Diets

These approaches maintain plant foods as the primary dietary component while allowing controlled amounts of high-quality animal proteins, potentially offering a practical middle ground for CKD patients [13].

Quality Considerations

Recent research has emphasized the importance of plant food quality, distinguishing between healthy plant-based diets (emphasizing whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, vegetable oils, tea, and coffee) and unhealthy plant-based diets (emphasizing fruit juices, refined grains, potatoes, sugar-sweetened beverages, and sweets). These results suggest that the quality of plant-based diets may be important for CKD management [14].

The distinction between different types of plant-based approaches is crucial for CKD management, as the nephroprotective benefits appear to depend heavily on food quality and processing levels rather than simply the exclusion of animal products.

Epidemiological Evidence: Plant-Based Diets and CKD Incidence

Large-scale epidemiological studies have provided compelling evidence for the protective effects of plant-based dietary patterns against CKD development. The most comprehensive analysis to date examined the relationship between plant-based diets and CKD risk across multiple populations and study designs.

Meta-Analysis Evidence

A major meta-analysis including 121,927 participants aged 18-74 years, followed for a weighted average of 11.2 years, found that adopting plant-based diets was associated with a reduced risk of developing CKD (OR = 0.75, 95% CI 0.65-0.86, P < 0.0001) across 93,857 participants [15] [16]. This analysis demonstrated that adopting plant-based diets was associated with 26% lower CKD incidence, with higher intake of plant-based diets showing a dose-dependent relationship with lower risk of CKD incidence and slower CKD progression [17].

Cohort Study Findings

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, examining 14,686 middle-aged adults, provided detailed insights into different types of plant-based dietary patterns. Higher adherence to a healthy plant-based diet (HR Q5 vs Q1: 0.86; 95% CI 0.78-0.96; P for trend = 0.001) and a provegetarian diet (HR Q5 vs Q1: 0.90; 95% CI 0.82-0.99; P for trend = 0.03) were associated with lower CKD risk, whereas higher adherence to a less healthy plant-based diet (HR Q5 vs Q1: 1.11; 95% CI 1.01-1.21; P for trend = 0.04) was associated with elevated risk [18].

The study also found that higher adherence to overall plant-based and healthy plant-based diets was associated with slower eGFR decline, with the proportion of CKD attributable to lower adherence to healthy plant-based diets being 4.1% (95% CI 0.6% to 8.3%) [19].

Cross-Sectional Studies

Supporting evidence comes from cross-sectional analyses, including the Ravansar cohort study of 9,746 Iranian adults. Participants with high plant-based diet scores had higher mean eGFR compared to those with low scores (79.20 ± 0.36 vs 72.95 ± 0.31, P < 0.001), with odds of CKD in the highest quartile being 39% lower than the lowest quartile after adjusting for confounders (OR: 0.61; 95% CI 0.48-0.78, P trend < 0.001) [20] [21].

Quality and Processing Effects

The epidemiological evidence consistently demonstrates that the quality of plant foods matters particularly for kidney health outcomes. Studies have shown that unhealthy plant-based diets may not confer renal protective effects compared to healthy plant-based diets [22], highlighting the importance of emphasizing whole, minimally processed plant foods rather than simply avoiding animal products.

These population-level findings provide strong evidence that plant-based dietary patterns, particularly those emphasizing high-quality whole plant foods, are associated with reduced CKD incidence and slower progression of kidney function decline. The consistency of findings across diverse populations and study designs strengthens the evidence base for plant-based approaches in CKD prevention.

Clinical Outcomes in Established CKD

While epidemiological studies demonstrate protective effects against CKD development, the evidence for plant-based diets in managing established CKD requires careful examination of clinical trials and cohort studies in patients with existing kidney disease.

Mortality and Progression Outcomes

The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study provides the most comprehensive data on plant-based diets in established CKD. In 2,539 individuals with CKD, higher adherence to overall plant-based and healthy plant-based diets was associated with 26% (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.62-0.88, P trend < 0.001) and 21% (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.66-0.95, P trend = 0.03) lower risks of all-cause mortality, respectively. Conversely, following an unhealthy plant-based diet was associated with higher risk of CKD progression and all-cause mortality [23].

During median follow-up periods of 7 and 12 years, there were 977 CKD progression events and 836 deaths. Each 10-point higher score of unhealthy plant-based diets was modestly associated with higher risk of CKD progression (HR 1.14, 95% CI 1.03-1.25) and all-cause mortality (HR 1.11, 95% CI 1.00-1.23) [24].

Kidney Function Outcomes

Clinical trials examining kidney function outcomes have shown promising results, though the evidence base remains limited. Observational studies suggest a possible benefit of consuming more plant-based protein compared with animal-based protein for preservation of kidney function and reduced signs of CKD-mineral bone disorder (CKD-MBD) [25] [26].

A notable case study demonstrated dramatic improvements in kidney function with a whole food plant-based approach. A 69-year-old man with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and stage 3 CKD saw his estimated GFR increase from 45 to 74 mL/min after 4.5 months on a strict whole-foods, plant-based diet, while his microalbumin/creatinine ratio decreased from 414.3 to 26.8 mg/g and phosphorus levels returned to normal range.

Metabolic Outcomes

In CKD patients, plant-based diets were associated with improved kidney function and favorable metabolic profiles, including beneficial effects on fibroblast growth factor-23, uremic toxins, insulin sensitivity, and inflammatory biomarkers [27]. These metabolic improvements suggest mechanisms beyond simple dietary restriction that may contribute to nephroprotection.

High-Diversity Plant Diet Studies

Recent research has examined the effects of increasing plant food diversity on CKD outcomes. Increasing plant diversity (≥30 plant foods per week) reduced symptom burden and shifted the gut microbiome toward beneficial metabolite production, with greater effectiveness observed in individuals with more advanced kidney disease and higher levels of uremic toxins at baseline [28].

High-diversity plant-based diets was noted to improved diet quality, reduced potential renal acid load by 47% from baseline, decreased total symptom burden including constipation, and shifted the gut microbiome toward increased production of beneficial metabolites such as butyrate [29].

Limitations in Clinical Evidence

Despite promising observational findings, current clinical trial evidence on plant-based protein interventions for preserving kidney function and preventing CKD-MBD remains limited to inform clinical guidelines, emphasizing the ongoing need to research the effects of plant-based protein on kidney function and CKD-MBD outcomes [30]. Guidelines have fallen short of recommending whole food plant-based diets for CKD given the lack of robust randomized controlled trial data [31].

The clinical evidence in established CKD, while promising, remains primarily observational with limited randomized controlled trial data. However, the consistency of findings across different populations and outcome measures supports the potential benefits of high-quality plant-based approaches in CKD management.

Mechanisms of Nephroprotection

Plant-based diets may confer nephroprotective benefits through multiple interconnected mechanisms that address the fundamental pathophysiological processes underlying CKD progression. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for optimizing dietary interventions and predicting therapeutic outcomes.

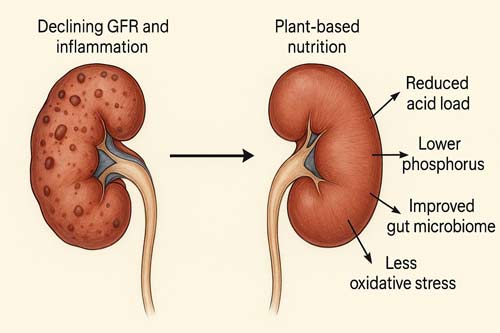

Dietary Acid Load Reduction

One of the most well-established mechanisms involves the reduction of dietary acid load. The average dietary acid load in CKD patients in the United States has been estimated at 55.15 mEq/day, markedly different from the negative acid load of a vegan diet estimated at -41.7 mEq/day. Higher dietary acid load has been associated with development of end-stage renal disease in CKD patients (P = 0.001) [32].

Plant-based diets have the potential to reduce dietary acid load and therefore help control acidosis, which is common in CKD and contributes to disease progression. Fruits and vegetables have been shown to be as effective as sodium bicarbonate in treating and preventing metabolic acidosis in CKD [33]. Although limited, experimental trials for treatment of metabolic acidosis in CKD with fruits and vegetables show outcomes comparable to oral bicarbonate [34].

Phosphorus Bioavailability and Management

Plant-based diets offer advantages in phosphorus management through reduced bioavailability and absence of phosphorus additives commonly found in processed animal products. Plant-based diets impact a lower phosphorus load due to lower bioavailability, which may help improve phosphorus control [35].

Phosphorus and potassium additives were found in 37% and 9% of meat, fish, and poultry products, respectively, increasing phosphorus content by 28% and potassium content by 277% compared to reference foods without additives [36]. Plant foods contain primarily organic phosphorus bound to phytate, which has approximately 40-60% lower bioavailability compared to the inorganic phosphorus found in animal products and processed foods.

Potassium Handling and Safety

Despite concerns about hyperkalemia, emerging evidence suggests that plant-based diets may actually improve potassium handling through multiple mechanisms. Evidence supporting dietary potassium restriction to prevent or treat hyperkalemia is lacking. In fact, plant-based diets may improve acidosis, constipation, and insulin resistance, all of which can impact serum potassium levels [37].

The risk of potassium overload from plant-based diets appears overstated, mostly opinion-based, and not supported by the evidence [38]. Knowledge that the bioavailability of potassium and phosphorus from plant-based foods is reduced has led to recent changes in international kidney-friendly diet recommendations [39].

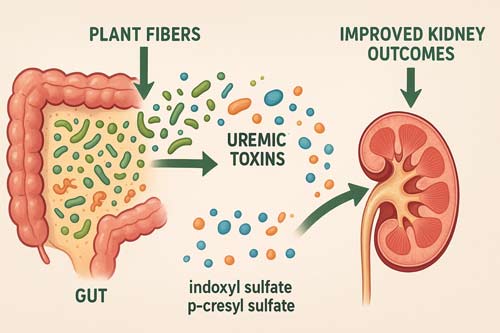

Gut Microbiome Modulation

Plant-based diets influence the gut microbiome composition and function, with important implications for uremic toxin production and systemic inflammation. Emerging evidence suggests that the higher fiber content of plant-based diets may help to modulate production of uremic toxins through beneficial shifts in the gut microbiome [40].

A habitual diet that favors higher intake of plant-based fiber and polysaccharides relative to proteins provides selective pressure on the gut microbiota and results in lower serum levels of uremic toxins [41]. Diet quality may influence uremic toxin generation and gut microbiota diversity, composition, and function in adults with CKD, warranting well-designed dietary intervention studies targeting uremic toxin production and gut microbiome impacts [42] [43].

Uremic Toxin Reduction

The production of protein-bound uremic toxins, including indoxyl sulfate, p-cresyl sulfate, and p-cresyl glucuronide, is closely linked to dietary protein source and gut microbiome composition. Higher adherence to plant-based diet indices was associated with lower total indoxyl sulfate levels, while higher adherence to unhealthy plant-based diets was associated with increases in both free and total indoxyl sulfate [44].

Protein-bound uremic toxins, including indoxyl sulfate, p-cresyl glucuronide, p-cresyl sulfate, and indole-3-acetic acid, progressively accumulate in CKD. Chronic kidney disease may be accompanied by intestinal inflammation and epithelial barrier impairment leading to systemic translocation of bacterial-derived uremic toxins and consequent oxidative stress injury [45].

Anti-inflammatory and Antioxidant Effects

Plant-based diets have both antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, and it is hypothesized that adherence to a plant-based diet may have a positive effect on kidney function [46]. Studies have shown a decreasing trend in C-reactive protein levels when consuming plant proteins compared to animal proteins among non-dialysis CKD participants [47].

Protein Quality and Amino Acid Profile

Contrary to traditional concerns about protein adequacy, plant-based proteins are not only adequate but are safe for CKD patients including those with proteinuria. Plant-based proteins are sufficient in meeting both quantity and quality requirements, with those eating primarily plant-based diets consuming approximately 1.0 g/kg/day of protein or more [48] [49].

Hemodynamic Effects

Plant-based diets in CKD may have benefits in the areas of hypertension, weight, hyperphosphatemia, reductions in hyperfiltration, and possibly mortality [50]. The reduction in glomerular hyperfiltration may be particularly important for slowing CKD progression, as sustained hyperfiltration is a key driver of nephron loss.

These multiple mechanisms work synergistically to provide nephroprotection, suggesting that plant-based approaches offer more comprehensive benefits than traditional single-nutrient restriction strategies. The evidence indicates that well-designed plant-based diets can address multiple pathophysiological pathways simultaneously while maintaining nutritional adequacy.

Safety Considerations and Clinical Concerns

While emerging evidence supports the potential benefits of plant-based diets in CKD management, several safety considerations and clinical concerns require careful evaluation. These concerns have historically limited the adoption of plant-based approaches and continue to influence clinical practice patterns.

Hyperkalemia Risk Assessment

Hyperkalemia represents one of the most frequently cited concerns regarding plant-based diets in CKD. Commonly cited potential harms include the risk of hyperkalemia in a diet high in fruits and vegetables, the risk of malnutrition in a diet devoid of animal protein, and the burden posed by cultural and socioeconomic barriers to successful adoption [51].

However, accumulating evidence challenges these traditional concerns. The risk of potassium overload from plant-based diets appears overstated, mostly opinion-based, and not supported by the evidence [52]. The risk of potassium overload from plant-based diets appears overstated and concerns of hyperkalemia related to plant-based diets may be outdated and unsupported by the current body of literature [53] [54].

Several factors may explain this apparent paradox:

- Bioavailability differences: Plant-based potassium has lower bioavailability compared to potassium additives in processed foods

- Improved acid-base balance: Plant-based diets improve metabolic acidosis, which enhances cellular potassium uptake

- Fiber effects: High fiber intake may promote potassium elimination through the colon

- Overall dietary pattern: Plant-based diets typically eliminate processed foods containing highly bioavailable potassium additives

Protein Adequacy and Quality

Traditional concerns about protein adequacy in plant-based diets for CKD patients stem from outdated concepts of “biological value” and essential amino acid profiles. Concerns regarding protein and amino acid deficiencies with plant-based proteins have precluded their use in CKD patients. Many of these concerns were debunked years ago, but recommendations persist regarding the use of “high-biological value” (animal-based) proteins, which may contribute to worsening of other parameters such as blood pressure, metabolic acidosis, and hyperphosphatemia [55].

Plant-based proteins are sufficient in meeting both quantity and quality requirements. Those eating primarily plant-based diets have been observed to consume approximately 1.0 g/kg/day of protein or more, and CKD patients have been seen to consume 0.7-0.9 g/kg/day of mostly plant-based protein without any negative effects [56].

Nutritional Deficiency Risks

Certain nutrients require attention in plant-based diets for CKD patients:

Vitamin B12: Exclusively found in animal products, requiring supplementation in vegan diets

Vitamin D: One study reported that vegetarian diets were associated with severe vitamin D deficiency compared to nonvegetarian diets [57]

Iron and Zinc: Plant-based forms have lower bioavailability but adequacy can be maintained with proper planning

Omega-3 fatty acids: EPA and DHA primarily from marine sources, though algae-based supplements are available

Medication Interactions and Monitoring

Plant-based diets may influence medication effectiveness and monitoring parameters:

- Creatinine-based eGFR accuracy: Potential limitations of creatinine-based GFR equations in the face of drastic weight loss must be considered

- Antihypertensive medications: Improved blood pressure control may require medication adjustments

- Phosphate binders: Reduced need may occur due to lower phosphorus bioavailability

Implementation and Adherence Challenges

Potential drawbacks include the need for specific knowledge, skills, and cost involved in preparing varied, healthy, and appetizing plant-based meals, leading to lower acceptability and accessibility to certain populations [58].

Patient Education and Support

Patients were not confident in their ability to plan balanced plant-based meals, and resources rated most helpful included sample meal plans, individual counseling with registered dietitian nutritionists, handouts, and cooking classes [59] [60].

Professional Perspectives

Among 644 nephrology professionals surveyed, 88% had heard of using plant-based diets for kidney disease treatment, and 88% believed it could improve CKD management, though dietitians were more likely to report plant-based diets as beneficial for each health condition [61] [62].

Clinical Monitoring Recommendations

Safe implementation requires:

- Regular laboratory monitoring of electrolytes, especially potassium

- Assessment of nutritional status and protein markers

- Vitamin B12 and vitamin D supplementation as needed

- Collaboration with qualified dietitians experienced in plant-based nutrition

- Gradual transition rather than abrupt dietary changes

Risk-Benefit Assessment

It is likely that the risks for both hyperkalemia and protein inadequacy may not have been as noteworthy as previously thought, while the advantages are vast. The risk to benefit ratio of plant-based diets appears to be tilting in favor of their more prevalent use [63].

The safety profile of well-planned plant-based diets in CKD appears favorable when implemented with appropriate medical supervision and nutritional guidance. However, individualized assessment and monitoring remain essential, particularly for patients with advanced CKD or multiple comorbidities.

Plant Protein versus Animal Protein: Clinical Evidence

The comparison between plant and animal proteins in CKD management represents a critical area of investigation, with mounting evidence suggesting that protein source may be as important as protein quantity in determining clinical outcomes.

Inflammatory Markers and Metabolic Effects

Recent meta-analyses have examined the differential effects of plant versus animal proteins on inflammatory markers in CKD patients. Proteins, especially plant proteins, may reduce inflammation among adults with CKD. A systematic review and meta-analysis found a decreasing trend in C-reactive protein levels when consuming plant proteins compared to animal proteins among non-dialysis participants [64] [65].

There was a statistically significant decrease when comparing animal proteins to unspecified proteins in CRP levels among dialysis participants (Hedges’ g = 2.11; 95% CI 1.12, 3.11; p ≤ 0.001). Furthermore, animal proteins (eggs, red meat) showed increasing trends in CRP levels compared to whey protein isolate [66].

Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes

The differential effects of protein sources extend beyond inflammation to encompass broader cardiovascular and renal outcomes. Animal protein consumption increases the risk of incident CKD in the general population while plant-sourced protein intake (legumes, soybeans, whole grains, nuts) reduces the risk. Animal protein intake elevates GFR, increases albuminuria, and accelerates the rate of kidney function decline while vegetable protein is kidney-protective [67].

The exclusive role of animal protein (versus plant-derived protein) increasing albuminuria has been confirmed in interventional trials. Animal protein consumption is strongly associated with kidney function decline in subjects from the general population and patients with diabetic kidney disease, independent of other risk factors [68].

Mechanistic Differences

The superior outcomes with plant proteins appear to stem from fundamental metabolic differences in how different protein sources are processed. The source of dietary protein (animal versus vegetable) contributes to determining the degree of insulin sensitivity and vascular risk. Animal protein consumption activates glucagon secretion and therefore intensifies insulin resistance whereas vegetable protein enhances insulin sensitivity [69].

Enhancement of insulin sensitivity afforded by vegan diets largely mediates their remarkable vascular advantages, with enhanced insulin sensitivity mediating the beneficial effect of plant-based diets [70] [71].

Lipid Profile Effects

A comprehensive meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials examining plant protein effects on lipid profiles in CKD patients provides important insights. While there is evidence that higher plant protein intake could ameliorate lipid levels in the general population, the effects of this dietary regimen within the CKD population remain uncertain, with studies providing conflicting results. This meta-analysis aimed to investigate the impact of increased plant protein intake on lipid levels of CKD patients [72].

Eleven trials encompassing 248 patients were included, examining the effect of increased plant protein intake versus the usual CKD animal-based diet in CKD patients [73].

Clinical Trial Evidence Limitations

Despite promising observational evidence, the 2020 KDOQI guideline reported limited evidence for the effects of protein source on traditional biochemical markers of nutrition status and inflammation, lipid panel measures, and serum calcium and phosphorus in CKD stages 1-5D and post-transplantation. Five randomized controlled trials published between 1998 and 2016 met criteria for guideline development, but outcomes of kidney function (eGFR, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine) and CKD-mineral bone disorder were not addressed [74].

Of identified studies, results for kidney function and CKD-MBD outcomes were heterogeneous, with most studies having suboptimal methodological quality. In most studies (27/32), protein source was altered only secondarily to low-protein diet interventions, with data synthesis focused on five studies that investigated protein source change only [75].

Specific Protein Source Studies

Individual studies examining specific plant protein sources have shown promising results:

Soy Protein: Multiple trials have examined soy protein effects, generally showing benefits for lipid profiles and inflammatory markers compared to animal proteins.

Legume-Based Proteins: Studies incorporating beans, lentils, and other legumes have demonstrated favorable effects on metabolic parameters.

Mixed Plant Proteins: Diets incorporating diverse plant protein sources appear to provide optimal amino acid profiles while maintaining metabolic benefits.

Protein Quality Considerations

The common belief that plants lack essential amino acids is inaccurate. While animal-based proteins are believed to be nutritionally superior due to higher essential amino acids per serving and better gastrointestinal bioavailability, in reality, all foods contain essential amino acids including plants (with the exception of gelatin which lacks tryptophan) [76].

Practical Implementation

Plant proteins are more effective and pronounced than animal proteins in reducing the rate of CKD progression, with benefit-risk ratios appearing greater for plant-based, less processed dietary patterns [77]. Patients with CKD respond to varying amounts of animal and vegetable protein differently than those with normal renal function, with this difference observed in both single-meal studies and clinical trials [78].

The evidence supporting plant over animal proteins in CKD management is substantial but primarily observational. While mechanistic understanding is strong and observational outcomes are consistently favorable, the need for high-quality randomized controlled trials specifically comparing protein sources in CKD patients remains a research priority. The available evidence suggests that gradual transition toward plant-based protein sources may offer multiple benefits for CKD patients when implemented with appropriate nutritional oversight.

Practical Implementation and Clinical Guidelines

The translation of research evidence into clinical practice requires careful consideration of implementation strategies, patient education, healthcare provider training, and integration with existing clinical guidelines. The growing evidence base for plant-based approaches in CKD management necessitates practical frameworks for safe and effective implementation.

Current Guideline Status

Current Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative guideline recommendations for patients with CKD include a diet that is low in protein (0.55-0.60 g/kg/day for nondiabetics and 0.60-0.80 g/kg/day for those with diabetes), high in fruits and vegetables (with consideration of potassium and phosphorous content to avoid elevated levels of these electrolytes), and low in sodium (<2.3 g/day). The Mediterranean diet is specifically recommended to optimize lipid profiles in individuals with CKD [79].

However, guidelines have fallen short of recommending whole food plant-based diets for CKD given the lack of robust randomized controlled trial data. Other sources with high visibility in the nephrology community have taken a clear stance on the role of plant-based diets for treating CKD [80].

The National Kidney Foundation promotes whole food plant-based diets on its website, and prominent journals have recently published positive reviews of plant-based diets for patients with CKD [81].

Professional Perspectives and Practice Patterns

Clinical practice patterns among nephrology providers show a wide range, with some having strong convictions toward whole food plant-based diets while others remain skeptical and wait for more convincing data [82]. Among surveyed nephrology professionals, 88% believed plant-based diets could improve CKD management, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol, and obesity, with dietitians more likely to report plant-based diets as beneficial for each health condition [83].

Professionals were most confident that plant-based diets could help control hypertension (3.75 ± 0.99 on a 1-5 scale), compared with delaying CKD progression (3.68 ± 1.15) or treating acidosis (3.68 ± 1.13). Dietitians felt more confident in their ability to plan balanced plant-based diets compared to other specialties (3.49 vs. 2.74, P < 0.001) [84].

Patient Perspectives and Barriers

Approximately half of CKD patients surveyed were familiar with plant-based diets, and most (58%) were aware that plant-based diets can improve CKD [85]. Survey results showed that approximately half of respondents were aware that plant-based diets can be beneficial for CKD, and many patients were already following vegetarian or plant-based eating patterns [86].

Common barriers to following plant-based diets included family eating preferences, meal planning skills, preference for meat, figuring out what is healthy to eat, food cost, time constraints, and ease of cooking (all rated equally at median = 3) [87].

Implementation Strategies

Graduated Approach

Rather than abrupt dietary changes, a graduated approach allows for:

- Phase 1: Increase plant food variety and reduce processed foods

- Phase 2: Substitute plant proteins for some animal proteins

- Phase 3: Transition to predominantly plant-based approach if appropriate

Educational Resources

Resources rated most helpful for transitioning to plant-based diets included sample meal plans, individual counseling sessions with registered dietitian nutritionists, handouts, and cooking classes [88].

Monitoring Protocols

Regular monitoring should include:

- Comprehensive metabolic panels (electrolytes, kidney function)

- Complete blood counts

- Nutritional markers (albumin, prealbumin, B12, vitamin D)

- Anthropometric measurements

- Symptom assessment questionnaires

Specific Dietary Recommendations

High-Quality Plant Foods

Plant-based diets can be safely implemented in CKD through building the diet around whole, high fiber foods, avoiding processed foods, and using recommended cooking methods to control potassium [89].

Priority foods include:

- Whole grains: Brown rice, quinoa, oats, barley

- Legumes: Beans, lentils, chickpeas (with appropriate preparation)

- Vegetables: Variety of colors and types, with attention to potassium content

- Fruits: Fresh, whole fruits over juices

- Nuts and seeds: In appropriate portions

- Plant oils: Olive oil, avocado oil

Foods to Limit or Avoid

- Processed plant foods with additives

- Refined sugars and sweetened beverages

- Highly processed meat alternatives

- Foods with phosphorus additives

Special Populations

Diabetes and CKD

Reducing animal meat while augmenting vegetable protein has demonstrated definite advantages regarding insulin sensitivity [90], making plant-based approaches particularly relevant for diabetic kidney disease.

Advanced CKD

Individuals with more advanced kidney disease and higher levels of uremic toxins may derive the greatest benefit from adopting high-diversity plant-based diets [91].

Pediatric CKD

Plant-based diets can be safely implemented in children with CKD through building the diet around whole, high fiber foods, avoiding processed foods, and using recommended cooking methods to control potassium. The health benefits compared to omnivorous diets in children with CKD need investigation [92].

Healthcare Team Approach

Successful implementation requires coordinated care involving:

- Nephrologists: Medical oversight and monitoring

- Registered Dietitians: Specialized in both CKD and plant-based nutrition

- Nurses: Patient education and support

- Pharmacists: Medication adjustments as needed

- Social Workers: Addressing socioeconomic barriers

Quality Assurance and Outcomes Monitoring

Programs implementing plant-based approaches should track:

- Clinical outcomes (eGFR, proteinuria, hospitalizations)

- Laboratory parameters (electrolytes, nutritional markers)

- Patient-reported outcomes (quality of life, satisfaction)

- Adherence and sustainability measures

- Adverse events and safety signals

Research Integration

Future studies should focus on large-scale randomized controlled trials to establish plant-based diet roles in CKD dietary guidelines and clinical practice. Clinical programs should be designed to contribute to the evidence base while providing care.

Cost-Effectiveness Considerations

Implementation programs should evaluate:

- Healthcare utilization changes

- Medication cost reductions

- Quality-adjusted life years

- Long-term sustainability

The practical implementation of plant-based approaches in CKD management requires systematic, evidence-based protocols that prioritize patient safety while allowing for the potential benefits suggested by current research. Success depends on multidisciplinary collaboration, appropriate patient selection, comprehensive monitoring, and continued research to refine best practices.

Future Directions and Research Priorities

The evolving evidence base for plant-based diets in CKD management reveals both promising opportunities and critical knowledge gaps that require systematic investigation. Future research must address methodological limitations, explore mechanistic pathways, and establish definitive clinical guidelines through well-designed studies.

Critical Research Gaps

Randomized Controlled Trial Evidence

The lack of robust randomized controlled trial data has prevented guidelines from recommending whole food plant-based diets for CKD [93]. Current clinical trial evidence on plant-based protein interventions for preserving kidney function and preventing CKD-mineral bone disorder is limited to inform clinical guidelines, emphasizing the ongoing need for research [94].

Priority areas for randomized controlled trials include:

- Dose-response relationships: Determining optimal plant food proportions

- Duration studies: Long-term effects over 2-5 years

- Comparative effectiveness: Plant-based versus standard CKD diets

- Mechanistic studies: Biomarker changes and pathway elucidation

Pediatric CKD Research

The effects of plant-based diets on progression of CKD remain controversial, and there are no data to support this in children [95] [96]. The health benefits of plant-based diets compared to omnivorous diets in children with CKD need investigation [97].

Research priorities for pediatric populations:

- Growth and development outcomes

- Nutritional adequacy during critical growth periods

- Long-term safety and efficacy

- Family-based intervention strategies

Advanced CKD Populations

Studies specifically examining plant-based approaches in:

- Stage 4-5 CKD patients

- Pre-dialysis populations

- Post-transplant recipients

- Elderly patients with CKD

Mechanistic Research Priorities

Gut Microbiome Studies

Well-designed dietary intervention studies targeting the production of uremic toxins and exploring the impact on gut microbiome are warranted in the CKD population [98] [99]. Future research should employ:

- Multi-omics approaches (metagenomics, metabolomics, proteomics)

- Longitudinal microbiome profiling

- Functional capacity analysis

- Host-microbe interaction studies

Uremic Toxin Production

Research priorities include:

- Identification of novel uremic toxins affected by plant-based diets

- Quantification of toxin reduction mechanisms

- Relationship between toxin levels and clinical outcomes

- Development of targeted interventions

Inflammation and Oxidative Stress

Studies examining:

- Inflammatory pathway modulation

- Antioxidant mechanism elucidation

- Biomarker development for monitoring

- Personalized intervention strategies

Methodological Improvements

Dietary Assessment and Standardization

Future studies require:

- Standardized definitions of plant-based diet types

- Validated dietary assessment tools specific to CKD

- Biomarker validation of dietary adherence

- Cultural adaptation of dietary interventions

Outcome Measurement

Priority outcomes for future trials:

- Primary endpoints: eGFR decline, time to dialysis, mortality

- Secondary endpoints: Quality of life, hospitalizations, medication requirements

- Mechanistic endpoints: Uremic toxins, inflammatory markers, gut microbiome

- Safety endpoints: Electrolyte disturbances, nutritional deficiencies

Technology Integration

Digital Health Solutions

Development of:

- Mobile applications for dietary tracking and education

- Telemedicine platforms for nutrition counseling

- Artificial intelligence for personalized meal planning

- Remote monitoring systems for safety parameters

Precision Nutrition Approaches

Research into:

- Genetic factors influencing plant-based diet response

- Microbiome-based dietary recommendations

- Metabolomic profiling for personalized interventions

- Pharmacogenomic interactions with plant-based compounds

Implementation Science Research

Healthcare System Integration

Studies examining:

- Provider training and education strategies

- Healthcare delivery model optimization

- Cost-effectiveness analyses

- Population health approaches

Health Equity and Access

Research priorities:

- Cultural adaptation of plant-based interventions

- Socioeconomic barrier identification and mitigation

- Food security considerations

- Rural and underserved population access

Collaborative Research Networks

Multi-Center Consortiums

Development of:

- International CKD nutrition research networks

- Standardized protocols and outcome measures

- Shared biorepositories and data resources

- Harmonized regulatory frameworks

Industry-Academia Partnerships

Collaboration opportunities:

- Food industry partnerships for product development

- Technology companies for digital health solutions

- Pharmaceutical companies for combination approaches

- Healthcare systems for implementation research

Regulatory and Policy Research

Guideline Development

Research to inform:

- Professional society guideline updates

- Regulatory agency recommendations

- Quality measure development

- Reimbursement policy decisions

Public Health Implications

Studies examining:

- Population-level implementation strategies

- Environmental sustainability impacts

- Healthcare cost implications

- Prevention program development

Innovative Study Designs

Adaptive Clinical Trials

Implementation of:

- Platform trials testing multiple interventions

- Adaptive randomization based on biomarkers

- Seamless phase II/III designs

- Master protocol approaches

Real-World Evidence Studies

Development of:

- Pragmatic clinical trials in routine care

- Electronic health record-based cohort studies

- Patient-reported outcome registries

- Comparative effectiveness research

Translational Medicine Priorities

Biomarker Discovery

Research into:

- Predictive biomarkers for treatment response

- Prognostic markers for disease progression

- Safety monitoring biomarkers

- Mechanistic pathway indicators

Therapeutic Target Identification

Investigation of:

- Novel molecular targets influenced by plant-based diets

- Pathway interactions and therapeutic opportunities

- Combination therapy approaches

- Personalized intervention strategies

The future of plant-based approaches in CKD management depends on rigorous scientific investigation addressing current evidence gaps while maintaining focus on patient safety and clinical effectiveness. Success will require coordinated efforts across research institutions, healthcare systems, industry partners, and regulatory agencies to generate the evidence needed for widespread clinical implementation.

Limitations and Methodological Considerations

Any analytical review of plant-based diets in CKD management must acknowledge major limitations in the current evidence base and methodological challenges that affect interpretation and clinical application of findings. These limitations are crucial for clinicians and researchers to understand when evaluating the strength of recommendations and designing future studies.

Study Design Limitations

Observational Study Bias

The majority of evidence supporting plant-based diets in CKD comes from observational studies, which are subject to multiple forms of bias:

Selection bias: Individuals choosing plant-based diets may differ systematically from those following conventional diets in health consciousness, socioeconomic status, and other health behaviors.

Confounding variables: Adherence to plant-based diets was more prevalent in those with higher socioeconomic status [100] [101], introducing potential confounding by socioeconomic factors that independently influence health outcomes.

Healthy user effect: Plant-based diet adherents may engage in other health-promoting behaviors that could account for observed benefits independent of the dietary intervention itself.

Randomized Controlled Trial Limitations

The few existing controlled trials have included non-randomized studies, which may have contributed to high risk of bias [102]. Results for kidney function and CKD-mineral bone disorder outcomes were heterogeneous, with most studies having suboptimal methodological quality [103] [104].

Specific limitations include:

- Small sample sizes reducing statistical power

- Short follow-up periods inadequate for chronic disease outcomes

- Heterogeneous intervention definitions

- Inconsistent outcome measurements

- High dropout rates affecting intention-to-treat analyses

Definitional and Classification Issues

Plant-Based Diet Heterogeneity

The term “plant-based diet” encompasses a broad spectrum of dietary patterns, creating challenges in comparing studies and interpreting results. While no formal definition of a “plant-based diet” exists, the term is commonly used to refer to various dietary patterns that promote plant foods, with plant-based diets not necessarily indicating complete avoidance of animal products [105].

This heterogeneity includes:

- Varying degrees of animal product inclusion

- Different processing levels of plant foods

- Inconsistent supplementation practices

- Variable attention to food quality versus quantity

Quality Assessment Challenges

Studies have shown that unhealthy plant-based diets may not confer renal protective effects compared to healthy plant-based diets [106], highlighting the critical importance of diet quality assessment. However, standardized methods for evaluating plant-based diet quality remain limited.

Measurement and Assessment Limitations

Dietary Assessment Accuracy

Traditional dietary assessment methods face particular challenges in plant-based diet research:

- Food frequency questionnaires may not adequately capture plant food diversity

- 24-hour recalls may miss day-to-day variation in plant food consumption

- Cultural differences in plant food preparation and consumption

- Seasonal variations in plant food availability and intake

Biomarker Limitations

Potential limitations of creatinine-based GFR equations must be considered in the face of marked weight loss, which commonly occurs with plant-based dietary interventions. This creates challenges in accurately assessing kidney function changes.

Outcome Measurement Standardization

Lack of standardized outcome definitions across studies limits meta-analysis capabilities and evidence synthesis. Different studies may use:

- Varying definitions of CKD progression

- Different eGFR equations

- Inconsistent proteinuria measurements

- Diverse composite endpoints

Population and Generalizability Limitations

Demographic Representation

Many studies have limited diversity in:

- Racial and ethnic representation

- Geographic distribution

- Socioeconomic status ranges

- Age group coverage

- Comorbidity profiles

Cultural and Regional Factors

Plant-based diet acceptance and implementation vary across:

- Cultural food traditions

- Religious dietary practices

- Regional food availability

- Economic accessibility

- Healthcare system structures

Safety Monitoring and Reporting

Adverse Event Reporting

Many studies provide inadequate reporting of:

- Electrolyte disturbances, particularly hyperkalemia

- Nutritional deficiency development

- Gastrointestinal side effects

- Patient-reported tolerability issues

Long-term Safety Data

Concerns remain regarding protein sufficiency, potassium management, and long-term adherence, with successful implementation requiring tailored meal planning, patient education, and regular clinical monitoring.

The limited duration of most studies prevents assessment of:

- Long-term nutritional adequacy

- Sustained clinical benefits

- Late-emerging safety signals

- Durability of dietary adherence

Analytical and Statistical Limitations

Residual Confounding

Despite statistical adjustments, observational studies may not fully account for:

- Unmeasured lifestyle factors

- Healthcare access and quality differences

- Medication adherence variations

- Genetic predispositions

Publication Bias

Potential bias toward positive results may exist due to:

- Greater likelihood of publishing favorable outcomes

- Industry influence on study funding and reporting

- Investigator enthusiasm for plant-based approaches

- Journal editorial preferences

Meta-analysis Challenges

Meta-analyses face challenges from controlled trials using random-effects models while including both randomized and non-randomized studies, which may contribute to high risk of bias [107].

Specific challenges include:

- Heterogeneous study designs and populations

- Varying intervention definitions and intensities

- Inconsistent outcome definitions

- Different follow-up periods

Clinical Translation Limitations

Implementation Complexity

The gap between research settings and clinical practice includes:

- Intensive interventions difficult to replicate in routine care

- Specialized personnel requirements

- Resource and cost considerations

- Patient selection criteria differences

Provider Training and Expertise

Dietitians felt more confident in their ability to plan balanced plant-based diets compared to other specialties [108], suggesting that successful implementation requires specialized expertise that may not be widely available.

Future Research Considerations

These limitations highlight the need for:

- Large-scale, well-designed randomized controlled trials

- Standardized dietary intervention definitions

- Comprehensive safety monitoring protocols

- Diverse population recruitment strategies

- Long-term follow-up studies

- Implementation research in real-world settings

Acknowledging these limitations is essential for appropriate interpretation of current evidence and responsible clinical application. While the available data suggest potential benefits of plant-based approaches in CKD management, the limitations underscore the need for continued rigorous research to establish definitive clinical recommendations.

Conclusion

The evidence examining plant-based diets in chronic kidney disease management reveals a complex but increasingly promising therapeutic approach that challenges traditional dietary paradigms in nephrology. This analytical review has synthesized current research spanning epidemiological studies, clinical trials, mechanistic investigations, and practical implementation considerations to provide a comprehensive assessment of this evolving field.

Summary of Key Findings

The epidemiological evidence provides compelling support for plant-based dietary patterns in CKD prevention and management. Large-scale meta-analyses demonstrate that adopting plant-based diets is associated with 26% lower CKD incidence, with a dose-dependent relationship between higher plant food intake and lower CKD risk and slower progression [109]. These population-level findings are supported by longitudinal cohort studies showing that higher adherence to healthy plant-based diets is associated with slower eGFR decline, with 4.1% of CKD attributable to lower adherence to healthy plant-based diets [110] [111].

In established CKD, clinical outcomes research reveals multiple potential benefits. The CRIC study demonstrated that adherence to overall and healthy plant-based diets was associated with 26% and 21% lower risks of all-cause mortality, respectively, while unhealthy plant-based diets increased risks of both progression and mortality [112]. These findings underscore the critical importance of diet quality over simple categorization, with whole, minimally processed plant foods providing optimal benefits.

The mechanistic understanding of plant-based diet effects in CKD has advanced substantially, revealing multiple complementary pathways for nephroprotection. Key mechanisms include dietary acid load reduction, improved phosphorus bioavailability, beneficial gut microbiome modulation, reduced uremic toxin production, and anti-inflammatory effects. Research demonstrates that diets favoring higher intake of plant-based fiber and polysaccharides relative to proteins provide selective pressure on gut microbiota and result in lower serum levels of uremic toxins [113]. These mechanistic insights provide biological plausibility for the clinical benefits observed in observational studies.

Addressing Traditional Concerns

This review reveals that many traditional concerns about plant-based diets in CKD may be outdated or overstated. The risk of potassium overload from plant-based diets appears overstated, mostly opinion-based, and not supported by current evidence, with concerns of hyperkalemia related to plant-based diets potentially being outdated and unsupported by the current literature [114] [115]. Similarly, plant-based proteins are sufficient in meeting both quantity and quality requirements, with CKD patients consuming 0.7-0.9 g/kg/day of mostly plant-based protein without negative effects [116] [117].

The emerging evidence suggests that the risks for both hyperkalemia and protein inadequacy may not have been as notable as previously thought, while the advantages are vast, with the risk-to-benefit ratio of plant-based diets appearing to tilt in favor of their more prevalent use [118].

Clinical Implementation Implications

The translation of research evidence into clinical practice requires careful consideration of implementation strategies and patient safety. While plant-based approaches appear nutritionally adequate, concerns remain regarding protein sufficiency, potassium management, and long-term adherence, requiring tailored meal planning, patient education, and regular clinical monitoring to optimize outcomes and mitigate potential risks.

Professional perspectives are evolving, with 88% of surveyed nephrology professionals believing plant-based diets could improve CKD management [119], though implementation patterns remain variable. Patient awareness and interest are growing, with approximately half of CKD patients aware that plant-based diets can be beneficial, and many already following vegetarian or plant-based eating patterns [120].

Quality and Heterogeneity Considerations

A critical finding of this review is the paramount importance of diet quality in determining outcomes. The quality of plant-based diets may be important for CKD management [121], with healthy plant-based approaches emphasizing whole foods, vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains showing benefits, while processed plant foods and refined carbohydrates may provide little benefit or even harm.

This quality consideration has important implications for clinical recommendations, suggesting that the focus should be on promoting high-quality plant foods rather than simply recommending plant-based diets broadly defined.

Research Priorities and Future Directions

Despite encouraging observational evidence, major gaps remain in the clinical trial literature. Current clinical trial evidence on plant-based protein interventions for preserving kidney function and preventing CKD-mineral bone disorder is limited to inform clinical guidelines [122]. Future studies should focus on large-scale randomized controlled trials to establish plant-based diet roles in CKD dietary guidelines and clinical practice.

Priority research areas include:

- Large-scale, long-term randomized controlled trials with hard clinical endpoints

- Mechanistic studies elucidating uremic toxin pathways and gut microbiome interactions

- Pediatric CKD research examining growth and development outcomes

- Implementation science research addressing real-world effectiveness and safety

- Health equity studies ensuring benefits are accessible across diverse populations

Practical Recommendations

Based on current evidence, several practical recommendations emerge for clinicians:

- Individualized Assessment: Evaluate each patient’s nutritional status, kidney function, comorbidities, and social factors before recommending plant-based approaches

- Graduated Implementation: Consider gradual transition rather than abrupt dietary changes, starting with increased plant food diversity and quality

- Multidisciplinary Approach: Involve registered dietitians with expertise in both CKD and plant-based nutrition, along with regular medical monitoring

- Quality Focus: Emphasize whole, minimally processed plant foods while avoiding processed plant-based products with additives

- Safety Monitoring: Implement regular laboratory monitoring for electrolytes, nutritional markers, and kidney function

- Patient Education: Provide comprehensive resources including meal planning assistance, cooking education, and ongoing support

Limitations and Cautions

This review acknowledges significant limitations in the current evidence base. The predominance of observational studies limits causal inference, while the heterogeneity of plant-based diet definitions complicates evidence synthesis. Most studies have had suboptimal methodological quality [123], and long-term safety data remain limited.

Healthcare providers must exercise clinical judgment in applying these findings, recognizing that individual patient responses may vary and that plant-based approaches may not be appropriate for all CKD patients. The need for specialized expertise in implementing plant-based diets safely in CKD populations cannot be overstated.

Final Perspective

The role of plant-based diets in slowing CKD progression represents an evolving area of clinical practice that offers both immense promise and important challenges. The current evidence suggests that well-planned, high-quality plant-based dietary approaches may provide multiple benefits for CKD patients, including improved outcomes for disease progression, mortality, and quality of life.

However, the evidence base requires strengthening through rigorous clinical trials before plant-based approaches can be universally recommended as standard care. In the interim, individualized implementation with appropriate medical supervision may be reasonable for selected patients, particularly those with early-stage CKD and strong motivation for dietary change.

Plant-based diets should be recommended for both primary and secondary prevention of CKD, with healthcare providers in general medicine and nephrology considering plant-based diets as an important tool for prevention and management of CKD [124] [125]. This represents a significant shift from traditional restrictive approaches toward more proactive, food-based therapeutic strategies.

The future of CKD management may well involve a more nuanced understanding of dietary interventions that goes beyond simple nutrient restriction to encompass the complex interactions between food quality, gut health, inflammation, and metabolic function. Plant-based approaches represent a promising component of this evolving therapeutic landscape, offering hope for improved outcomes while requiring continued scientific investigation to optimize implementation and ensure safety.

As the evidence continues to evolve, clinicians, researchers, and patients must work together to advance our understanding of plant-based approaches in CKD management, ensuring that therapeutic innovations are grounded in rigorous science while remaining responsive to individual patient needs and preferences. The ultimate goal remains improved quality of life and clinical outcomes for the millions of individuals affected by chronic kidney disease worldwide.

Key References

- Joshi, S., McMacken, M., & Kalantar-Zadeh, K. (2021). Plant-Based Diets for Kidney Disease: A Guide for Clinicians. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 77(2), 287-296.

- Kim, H., & Rebholz, C. M. (2024). Plant-based diets for kidney disease prevention and treatment. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension, 33(6), 593-602.

- Joshi, S., Hashmi, S., Shah, S., & Kalantar-Zadeh, K. (2020). Plant-based diets for prevention and management of chronic kidney disease. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension, 29(1), 16-21.

- Piccoli, G. B., et al. (2023). The Role of Plant-Based Diets in Preventing and Mitigating Chronic Kidney Disease: More Light than Shadows. Nutrients, 15(18), 4077.

- Freeman, N. S., & Turner, J. M. (2023). In the “Plant-Based” Era, Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease Should Focus on Eating Healthy. Journal of Renal Nutrition, 33(6), S6-S12.

- Nhan, J., Sgambat, K., & Moudgil, A. (2023). Plant-based diets: a fad or the future of medical nutrition therapy for children with chronic kidney disease? Pediatric Nephrology, 38(11), 3597-3609.

- Amir, S., et al. (2024). Adherence to Plant-Based Diets and Risk of CKD Progression and All-Cause Mortality: Findings From the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 83(5), 624-635.

- Betz, M. V., Nemec, K. B., & Zisman, A. L. (2022). Patient Perception of Plant Based Diets for Kidney Disease. Journal of Renal Nutrition, 32(5), 542-551.

- Multiple authors (2025). Plant-Based Diet and Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Renal Nutrition, 35(1), 56-63.

- Multiple authors (2023). Association Between Plant-based Diet and Kidney Function in Adults. Journal of Renal Nutrition, 34(4), 391-400.

- Betz, M. V., Nemec, K. B., & Zisman, A. L. (2021). Plant-based Diets in Kidney Disease: Nephrology Professionals’ Perspective. Journal of Renal Nutrition, 32(5), 552-559.

- Kim, H., & Rebholz, C. M. (2024). Plant-based diets for kidney disease prevention and treatment. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension, 33(6), 593-602.

- Betz, M. V., Nemec, K. B., & Zisman, A. L. (2022). Patient Perception of Plant Based Diets for Kidney Disease. Journal of Renal Nutrition, 32(5), 542-551.

References

[1] Plant-Based Diet and Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1051227625000275

[2] Adherence to Plant-Based Diets and Risk of CKD Progression and All-Cause Mortality: Findings From the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38103719/

[3] The Role of Plant-Based Diets in Preventing and Mitigating Chronic Kidney Disease: More Light than Shadows – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37834781/

[4] The Role of Plant-Based Diets in Preventing and Mitigating Chronic Kidney Disease: More Light than Shadows – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37834781/

[5] Plant-Based Diets for Kidney Disease: A Guide for Clinicians – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33075387/

[6] Plant-Based Diets for Kidney Disease: A Guide for Clinicians – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33075387/

[7] Plant-Based Diets for Kidney Disease: A Guide for Clinicians – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33075387/

[8] The Role of Plant-Based Diets in Preventing and Mitigating Chronic Kidney Disease: More Light than Shadows – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37834781/

[9] Plant-based diets for prevention and management of chronic kidney disease – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31725014/

[10] Plant-Based Diets for Kidney Disease: A Guide for Clinicians – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33075387/

[11] Plant-based diets for prevention and management of chronic kidney disease – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31725014/

[12] Diet Quality and Protein-Bound Uraemic Toxins: Investigation of Novel Risk Factors and the Role of Microbiome in Chronic Kidney Disease – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1051227621002387

[13] Diet Quality and Protein-Bound Uraemic Toxins: Investigation of Novel Risk Factors and the Role of Microbiome in Chronic Kidney Disease – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1051227621002387

[14] Adherence to Plant-Based Diets and Risk of CKD Progression and All-Cause Mortality: Findings From the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38103719/

[15] Plant-Based Diet and Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1051227625000275

[16] Plant-Based Diet and Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1051227625000275

[17] Plant-Based Diet and Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis – ScienceDirect – www.sciencedirect.comhttps://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1051227625000275

[18] Association Between Plant-based Diet and Kidney Function in Adults – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1051227623001528

[19] Association Between Plant-based Diet and Kidney Function in Adults – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1051227623001528

[20] Plant-based diets for CKD patients, green- based Mediterranean diet: A green nephrology view – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1473050225001697

[21] Plant-based diets for CKD patients, green- based Mediterranean diet: A green nephrology view – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1473050225001697

[22] Plant-Based Diet and Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1051227625000275

[23] Adherence to Plant-Based Diets and Risk of CKD Progression and All-Cause Mortality: Findings From the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38103719/

[24] A Plant-Dominant Low-Protein Diet in Chronic Kidney Disease Management: A Narrative Review with Considerations for Cyprus – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40289931/

[25] A review on animal and plant proteins in regulating diabetic kidney disease: Mechanism of action and future perspectives – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1756464624003554

[26] A review on animal and plant proteins in regulating diabetic kidney disease: Mechanism of action and future perspectives – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1756464624003554

[27] Patient Perception of Plant Based Diets for Kidney Disease – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1051227622001650

[28] A Link between Chronic Kidney Disease and Gut Microbiota in Immunological and Nutritional Aspects – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34684638/

[29] A Link between Chronic Kidney Disease and Gut Microbiota in Immunological and Nutritional Aspects – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34684638/

[30] A review on animal and plant proteins in regulating diabetic kidney disease: Mechanism of action and future perspectives – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1756464624003554

[31] Adherence to Plant-Based Diets and Risk of CKD Progression and All-Cause Mortality: Findings From the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272638623009368

[32] Plant-based diets for kidney disease prevention and treatment – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39115418/

[33] Plant-Based Diets for Kidney Disease: A Guide for Clinicians – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33075387/

[34] Plant-based diets: a fad or the future of medical nutrition therapy for children with chronic kidney disease? – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36786858/

[35] Plant-Based Diets for Kidney Disease: A Guide for Clinicians – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33075387/

[36] Plant-based diets for kidney disease prevention and treatment – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39115418/

[37] Plant-based diets for kidney disease prevention and treatment – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39115418/

[38] Plant-based diets: a fad or the future of medical nutrition therapy for children with chronic kidney disease? – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36786858/

[39] Plant-Based Diets in CKD – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30587492/

[40] Plant-Based Diets in CKD – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30587492/

[41] Diet Quality and Protein-Bound Uraemic Toxins: Investigation of Novel Risk Factors and the Role of Microbiome in Chronic Kidney Disease – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34776340/

[42] Chronic kidney disease and gut microbiota – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37609403/

[43] Chronic kidney disease and gut microbiota – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37609403/

[44] Influence of Plant and Animal Proteins on Inflammation Markers among Adults with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34068841/

[45] Plant-based diets: a fad or the future of medical nutrition therapy for children with chronic kidney disease? – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36786858/

[46] In the “Plant-Based” Era, Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease Should Focus on Eating Healthy – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1051227623001310

[47] Animal versus plant-based protein and risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37050925/

[48] Diet Quality and Protein-Bound Uraemic Toxins: Investigation of Novel Risk Factors and the Role of Microbiome in Chronic Kidney Disease – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1051227621002387

[49] Diet Quality and Protein-Bound Uraemic Toxins: Investigation of Novel Risk Factors and the Role of Microbiome in Chronic Kidney Disease – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1051227621002387

[50] Plant-based diets: a fad or the future of medical nutrition therapy for children with chronic kidney disease? – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36786858/

[51] Plant-based diets for prevention and management of chronic kidney disease – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31725014/

[52] Plant-based diets: a fad or the future of medical nutrition therapy for children with chronic kidney disease? – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36786858/

[53] Plant-based dietary approach to stage 3 chronic kidney disease with hyperphosphataemia – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31874846/

[54] Plant-based dietary approach to stage 3 chronic kidney disease with hyperphosphataemia – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31874846/

[55] In the “Plant-Based” Era, Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease Should Focus on Eating Healthy – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1051227623001310

[56] In the “Plant-Based” Era, Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease Should Focus on Eating Healthy – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1051227623001310

[57] Patient Perception of Plant Based Diets for Kidney Disease – ScienceDirect – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1051227622001650

[58] Plant-based diets for prevention and management of chronic kidney disease – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31725014/

[59] Patient Perception of Plant Based Diets for Kidney Disease – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36155085/