Thyroid Cancer Overdiagnosis When Screening Causes More Harm Than Good

Abstract

The incidence of thyroid cancer has risen substantially over the past three decades, drawing increased attention from clinicians, researchers, and public health authorities. Much of this rise has been attributed not to a true surge in aggressive disease, but rather to advances in diagnostic imaging, widespread use of high resolution ultrasonography, and greater healthcare utilization. These tools have enabled the detection of increasingly small thyroid nodules, including subclinical papillary thyroid carcinomas that might otherwise have remained undetected throughout a patient’s lifetime. This epidemiological pattern has prompted growing concern regarding overdiagnosis, defined as the identification of cancers that would never have produced symptoms, morbidity, or mortality if left undiscovered.

A critical observation supporting the overdiagnosis hypothesis is the discordance between incidence and mortality trends. While the number of diagnosed thyroid cancer cases has increased markedly, disease specific mortality has remained relatively stable in many regions. This suggests that a significant proportion of newly detected tumors are biologically indolent and unlikely to progress to clinically meaningful disease. The phenomenon is particularly evident in papillary thyroid microcarcinomas, which often demonstrate slow growth kinetics and low metastatic potential. Improved understanding of tumor biology has revealed that many of these lesions follow a benign course, raising important questions about the value of aggressive detection strategies.

The biological basis of overdiagnosis is closely linked to the heterogeneity of thyroid tumors. Molecular studies have shown that thyroid cancers exist along a spectrum ranging from highly indolent to more aggressive subtypes with invasive potential. However, current diagnostic pathways frequently fail to distinguish reliably between these categories at the time of detection. As a result, patients diagnosed with low risk tumors are often exposed to interventions that may not confer meaningful clinical benefit. This underscores the importance of aligning diagnostic intensity with the biological behavior of disease rather than relying solely on the presence of malignant cells.

The consequences of overdiagnosis extend beyond epidemiological statistics and have tangible psychological and physical effects on patients. A cancer diagnosis can provoke substantial emotional distress, including anxiety, depression, and altered self perception, even when the prognosis is excellent. From a clinical standpoint, overtreatment may expose patients to avoidable risks such as surgical complications, including recurrent laryngeal nerve injury and hypoparathyroidism, as well as the long term implications of lifelong thyroid hormone replacement following thyroidectomy. Additional treatments, such as radioactive iodine therapy, may further contribute to both acute and chronic adverse effects without clear evidence of benefit in low risk disease.

Healthcare systems also bear the economic burden associated with unnecessary diagnostic procedures, surgeries, and long term surveillance. Resource allocation toward the management of indolent tumors may inadvertently divert attention from higher risk conditions that require more intensive care. Consequently, the challenge for modern endocrinology and oncology is not simply to detect thyroid cancer, but to ensure that detection translates into meaningful improvements in patient outcomes.

Emerging evidence supports a more selective and patient centered approach to thyroid nodule evaluation. Risk stratification frameworks that incorporate ultrasound characteristics, nodule size thresholds, cytological findings, and when appropriate, molecular testing can help clinicians differentiate nodules that warrant biopsy from those suitable for observation. Active surveillance has gained acceptance as a safe alternative to immediate surgery for carefully selected patients with low risk papillary microcarcinoma, reflecting a broader shift toward conservative management when supported by clinical evidence.

Importantly, routine thyroid cancer screening in asymptomatic individuals is increasingly discouraged by many professional organizations due to the absence of demonstrated mortality benefit and the well documented risks of overdiagnosis. Instead, clinicians are encouraged to focus on high value care by reserving diagnostic evaluation for patients with clinically significant findings, compressive symptoms, suspicious imaging, or relevant risk factors such as prior radiation exposure or strong family history.

For healthcare providers, a clear understanding of the distinction between detection and clinical benefit is essential. Effective communication with patients regarding the natural history of many thyroid cancers can support shared decision making and reduce the likelihood of unnecessary intervention. Counseling should emphasize that not all detected cancers pose the same threat, and that in some cases, careful monitoring may represent the most appropriate strategy.

In conclusion, the rising incidence of thyroid cancer illustrates the unintended consequences of highly sensitive diagnostic technologies when applied without adequate risk stratification. While early detection remains a cornerstone of cancer control in many contexts, thyroid cancer highlights the importance of balancing vigilance with restraint. Moving forward, integrating evidence based guidelines, refining diagnostic thresholds, and prioritizing individualized care will be critical to minimizing harm while preserving the benefits of modern medical practice.

Introduction

The diagnostic landscape of thyroid cancer has undergone a profound transformation since the 1980s. Once considered a relatively uncommon malignancy, thyroid cancer is now diagnosed with increasing frequency, with incidence rates reported to have tripled across many developed nations. This rise has occurred alongside major technological advances in medical imaging, particularly the widespread adoption of high resolution ultrasonography and cross sectional modalities such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. These tools are capable of identifying thyroid nodules measuring as little as 2 to 3 millimeters, enabling detection of structural abnormalities that would previously have remained clinically silent.

Although enhanced diagnostic sensitivity has improved the ability to identify thyroid pathology, it has also contributed to the growing recognition of overdiagnosis as a concern in contemporary endocrine and oncologic practice. Overdiagnosis refers to the detection of cancers that, if left undiscovered, would not have produced symptoms, functional impairment, or mortality during a patient’s lifetime. In the context of thyroid cancer, this phenomenon creates a clinical paradox. Technologies developed to promote early detection and improve survival may instead expose patients to psychological distress, unnecessary diagnostic procedures, and potentially avoidable therapeutic interventions without delivering meaningful health benefits.

A comprehensive understanding of thyroid cancer overdiagnosis requires careful consideration of tumor biology. Thyroid malignancies demonstrate substantial heterogeneity, particularly within papillary thyroid carcinoma, which accounts for the majority of cases. Many small papillary tumors exhibit indolent growth patterns, low metastatic potential, and excellent long term survival even in the absence of immediate intervention. Autopsy studies have further reinforced this concept by revealing a notable prevalence of occult thyroid microcarcinomas in individuals who died from unrelated causes. These findings suggest that a proportion of detected tumors may never progress to clinically significant disease.

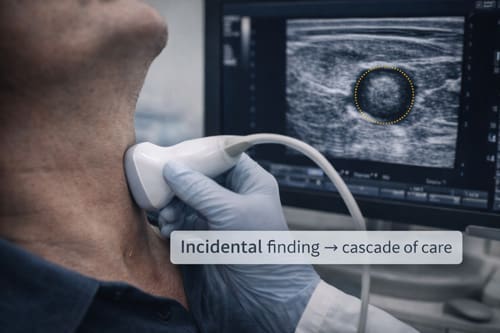

The expansion of imaging performed for unrelated medical indications has further accelerated detection rates. Incidental thyroid nodules are frequently identified during carotid ultrasonography, cervical spine imaging, trauma evaluations, and thoracic scans. Once discovered, these nodules often trigger a cascade of diagnostic evaluations that may include repeat imaging, fine needle aspiration biopsy, molecular testing, and surgical consultation. While each step is intended to clarify risk, the cumulative process can lead to overtreatment, particularly when low risk lesions are managed aggressively despite favorable prognostic indicators.

The clinical consequences of overdiagnosis are multifaceted. Surgical interventions such as thyroidectomy, although generally safe, carry risks including recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, hypoparathyroidism, hemorrhage, and the lifelong requirement for thyroid hormone replacement therapy. Even when complications are avoided, the transition from healthy individual to cancer patient can impose a lasting psychological burden characterized by anxiety, altered self perception, and reduced quality of life. For some patients, the knowledge of harboring a malignancy may influence employment, insurance eligibility, and long term health behaviors despite the tumor’s minimal biological threat.

Beyond the individual patient, thyroid cancer overdiagnosis presents broader systemic challenges. Healthcare systems must absorb rising costs associated with diagnostic imaging, cytopathology, surgical treatment, postoperative care, and long term surveillance. This increased utilization raises important questions regarding resource allocation, particularly in settings where competing health priorities demand careful stewardship of limited clinical capacity. Ethical considerations also emerge, as clinicians must balance the imperative to diagnose disease with the responsibility to avoid causing harm through unnecessary intervention.

Growing awareness of this issue has prompted reevaluation of diagnostic thresholds and management strategies. Contemporary clinical guidance increasingly emphasizes risk stratification, selective use of biopsy for nodules meeting defined size and sonographic criteria, and the consideration of active surveillance for appropriately selected low risk tumors. These approaches reflect a broader shift toward individualized care that prioritizes clinical relevance over purely anatomical detection.

This paper critically examines the evidence supporting the existence and scale of thyroid cancer overdiagnosis, explores the epidemiological and technological forces driving this trend, and evaluates its implications for patients and healthcare systems. It also provides practical recommendations for clinicians aimed at promoting evidence based decision making, enhancing patient counseling, and reducing unnecessary intervention while maintaining vigilance for clinically significant disease. Through a balanced assessment of benefits and harms, the discussion seeks to support a more judicious and patient centered approach to thyroid cancer diagnosis in an era of increasingly sensitive medical technology.

The Epidemiology of Thyroid Cancer Overdiagnosis

Rising Incidence Without Mortality Reduction

Thyroid cancer incidence rates have increased substantially across multiple countries and healthcare systems. In the United States, the age-adjusted incidence rate increased from 4.9 per 100,000 in 1975 to 15.4 per 100,000 in 2017. Similar patterns have been observed in South Korea, where incidence rates increased fifteen-fold between 1999 and 2008 following implementation of national screening programs.

Despite these dramatic increases in incidence, thyroid cancer mortality rates have remained relatively stable. The age-adjusted mortality rate in the United States has fluctuated between 0.4 and 0.5 per 100,000 over the same period when incidence tripled. This discordance between incidence and mortality represents a hallmark of overdiagnosis, suggesting that many newly identified cancers would never have caused death.

The size distribution of diagnosed thyroid cancers provides additional evidence for overdiagnosis. The increase in incidence has been driven primarily by small papillary thyroid cancers, particularly those measuring less than 2 centimeters in diameter. Large thyroid cancers, which are more likely to cause symptoms and death, have not increased proportionally. This pattern indicates that enhanced detection capability is identifying cancers that would have remained clinically silent.

Geographic Variations in Practice Patterns

International comparisons reveal striking variations in thyroid cancer incidence that correlate with healthcare utilization patterns rather than underlying disease prevalence. Countries with higher rates of medical imaging and routine health examinations demonstrate correspondingly higher thyroid cancer incidence rates. These variations cannot be explained by environmental factors, genetic differences, or known risk factors for thyroid cancer.

The Republic of Korea provides a natural experiment in thyroid cancer screening effects. Following introduction of thyroid ultrasonography as part of routine health examinations, thyroid cancer became the most commonly diagnosed cancer in Korean women. However, when screening recommendations were modified in 2014 to discourage routine thyroid cancer screening, incidence rates began to decline without any increase in mortality.

Finland and neighboring countries demonstrate similar healthcare systems but different approaches to thyroid nodule evaluation. Countries with more aggressive diagnostic approaches show higher thyroid cancer incidence without corresponding improvements in population health outcomes. These natural experiments provide compelling evidence that screening intensity drives diagnosis rates rather than detecting clinically important disease.

Biological Basis of Thyroid Cancer Overdiagnosis

Tumor Biology and Natural History

The biological characteristics of thyroid cancer explain why overdiagnosis occurs frequently in this organ system. Papillary thyroid carcinoma, which comprises approximately 85% of all thyroid cancers, often exhibits indolent behavior with slow growth rates and limited metastatic potential. Many papillary thyroid cancers demonstrate growth rates measured in years or decades rather than months.

Autopsy studies reveal the true prevalence of occult thyroid cancer in the general population. These studies consistently demonstrate that 5-35% of individuals who died from other causes harbor small papillary thyroid cancers that were never diagnosed during life. The wide range in reported prevalence reflects differences in sectioning techniques and pathological examination protocols, but all studies confirm that thyroid cancer is far more common at autopsy than in clinical practice.

The concept of cancer dormancy applies particularly well to thyroid cancer. Many small papillary thyroid cancers appear to reach a stable size and remain unchanged for years. Some cancers may even regress spontaneously. This biological behavior contrasts sharply with aggressive cancers that require prompt treatment to prevent death.

Molecular studies have identified genetic alterations that correlate with indolent tumor behavior. Thyroid cancers with specific mutation patterns, particularly those involving RET/PTC rearrangements, often demonstrate slow growth and limited invasive potential. These molecular markers may eventually help distinguish cancers that require treatment from those that can be safely monitored.

The Reservoir Effect

The reservoir effect describes the large pool of indolent cancers present in the population that can be detected through screening but would never cause clinical problems. For thyroid cancer, this reservoir is particularly large due to the high prevalence of small papillary cancers demonstrated in autopsy studies.

When screening programs are implemented, they rapidly identify cancers from this reservoir, creating an artificial epidemic of disease. The size of the reservoir determines how long increased diagnosis rates will continue before reaching equilibrium. For thyroid cancer, the large reservoir means that screening can continue to identify new cancers for many years without improving population health outcomes.

The reservoir effect explains why discontinuing thyroid cancer screening does not result in immediate increases in advanced cancer or mortality rates. Most cancers in the reservoir will never progress to become clinically apparent, even without treatment. This understanding challenges traditional assumptions about early detection and the importance of identifying all cancers.

Evidence for Overdiagnosis

Population-Based Studies

Multiple population-based studies have quantified the extent of thyroid cancer overdiagnosis. A systematic review published in 2016 estimated that 50-90% of thyroid cancers diagnosed in women and 70-80% of those diagnosed in men represent overdiagnosis in countries with high healthcare utilization. These estimates are based on mathematical modeling that compares observed incidence trends with stable mortality rates.

The French EDIFICE study examined thyroid cancer trends in a population with relatively low screening rates. This study found that areas with higher medical density and greater healthcare access demonstrated higher thyroid cancer incidence without corresponding improvements in outcomes. The relationship between healthcare intensity and diagnosis rates provides strong evidence for overdiagnosis.

Studies from the Veterans Health Administration system in the United States demonstrate similar patterns. Veterans receiving care at facilities with more aggressive diagnostic approaches show higher thyroid cancer incidence rates. However, long-term follow-up reveals no differences in thyroid cancer mortality between facilities with different diagnostic intensities.

Natural History Studies

Several studies have examined the natural history of small thyroid cancers managed with active surveillance rather than immediate treatment. These studies provide direct evidence about the clinical course of cancers that might represent overdiagnosis.

Japanese investigators have followed patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinomas (cancers less than 1 centimeter) using active surveillance protocols. After 10 years of follow-up, only 8% of tumors increased in size by 3 millimeters or more, and only 4% developed lymph node metastases. No patients died from thyroid cancer during the observation period.

Similar active surveillance studies from other countries confirm that many small thyroid cancers remain stable over time. The low rates of progression observed in these studies support the conclusion that many small thyroid cancers would never have caused clinical problems if left undetected and untreated.

Modeling Studies

Mathematical models have been developed to estimate the magnitude of thyroid cancer overdiagnosis. These models typically compare observed incidence trends with expected patterns based on stable mortality rates and known cancer biology.

A model developed by researchers at the National Cancer Institute estimated that approximately 90,000 cases of thyroid cancer diagnosed in the United States between 1988 and 2010 represented overdiagnosis. This represents nearly 60% of all thyroid cancers diagnosed during this period. The model accounts for improvements in treatment and potential lead-time bias.

Similar modeling approaches applied to data from other countries yield comparable estimates of overdiagnosis. Studies from Australia, Italy, and France suggest that 70-90% of the increase in thyroid cancer incidence represents overdiagnosis rather than a true increase in clinically relevant disease.

Harms of Overdiagnosis

Physical Harms

Thyroid cancer treatment carries substantial risks that must be weighed against potential benefits. Total thyroidectomy, the standard treatment for most thyroid cancers, results in permanent hypothyroidism requiring lifelong hormone replacement therapy. Achieving optimal hormone replacement can be challenging, and many patients experience persistent symptoms despite apparently adequate treatment.

Surgical complications occur in a minority of patients but can be severe. Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury affects 1-3% of patients undergoing thyroidectomy by experienced surgeons, resulting in vocal cord paralysis and voice changes. Permanent hypoparathyroidism occurs in 2-4% of patients, causing chronic hypocalcemia that requires careful management with calcium and vitamin D supplementation.

The table below summarizes the major physical harms associated with thyroid cancer treatment:

| Complication | Frequency | Duration | Clinical Impact |

| Hypothyroidism | >95% | Permanent | Requires lifelong medication |

| Vocal cord paralysis | 1-3% | Usually permanent | Voice changes, swallowing difficulty |

| Hypoparathyroidism | 2-4% | Permanent | Chronic hypocalcemia, tetany |

| Surgical site infection | 1-2% | Temporary | Pain, delayed healing |

| Bleeding/hematoma | <1% | Temporary | May require reoperation |

Radioactive iodine treatment, often administered after thyroidectomy, carries additional risks. Patients must observe radiation precautions that can interfere with work and family relationships. Salivary gland dysfunction affects 20-30% of patients receiving radioactive iodine, causing dry mouth and altered taste sensation. Secondary malignancies may occur years after radioactive iodine treatment, although the absolute risk remains low.

Psychological Harms

The psychological impact of a cancer diagnosis extends far beyond the immediate stress of receiving the news. Many patients develop anxiety disorders, depression, and post-traumatic stress symptoms following thyroid cancer diagnosis. These psychological effects persist even when treatment is successful and prognosis is excellent.

Cancer worry affects not only patients but also their family members and loved ones. Spouses and children of thyroid cancer patients demonstrate increased anxiety levels and healthcare utilization. The family impact of cancer diagnosis creates ripple effects that extend throughout social networks.

Employment discrimination and insurance issues represent additional psychological burdens. Despite legal protections, some thyroid cancer survivors face workplace discrimination or difficulty obtaining life insurance. These practical consequences of cancer diagnosis can persist for years after successful treatment.

The medicalization of normal anatomy represents another form of psychological harm. Patients who receive unnecessary thyroid cancer diagnoses become lifelong patients within the healthcare system. They require regular monitoring, blood tests, and imaging studies that serve as constant reminders of their cancer history.

Economic Consequences

Thyroid cancer treatment imposes substantial economic burdens on patients and healthcare systems. The average cost of initial thyroid cancer treatment ranges from $20,000 to $50,000, depending on the extent of surgery and whether radioactive iodine is administered. These costs do not include long-term follow-up care and hormone replacement therapy.

Lost productivity represents an additional economic burden. Most patients require 4-6 weeks off work following thyroidectomy. Some patients experience prolonged recovery periods due to complications or difficulty achieving optimal hormone replacement. The economic impact extends to family members who may need time off work to provide care and support.

Healthcare system costs multiply when overdiagnosis is widespread. Countries with high rates of thyroid cancer diagnosis face enormous healthcare expenditures without corresponding improvements in population health outcomes. These resources could be allocated to interventions with proven benefits rather than treating cancers that pose minimal threat to patient health.

Applications and Clinical Practice

Risk Stratification Approaches

Effective management of thyroid nodules requires risk stratification to identify patients who are most likely to benefit from further evaluation. Several clinical prediction tools have been developed to estimate the probability that a thyroid nodule represents cancer and, more importantly, whether that cancer requires treatment.

The American Thyroid Association risk stratification system classifies thyroid nodules based on ultrasound characteristics. High-suspicion nodules demonstrate features such as irregular margins, marked hypoechogenicity, and microcalcifications. These nodules warrant further evaluation with fine-needle aspiration biopsy when they meet size thresholds.

Molecular testing of thyroid nodules provides additional risk stratification information. Tests such as the Afirma Gene Expression Classifier and ThyroSeq can help identify nodules with low cancer risk, potentially avoiding unnecessary surgery. However, these tests must be used judiciously to avoid simply shifting overdiagnosis from one technology to another.

Patient factors also influence risk stratification decisions. Age, sex, radiation exposure history, and family history of thyroid cancer all affect the probability that a nodule represents clinically important cancer. Older patients may be less likely to benefit from treatment of small, low-risk cancers due to competing causes of mortality.

Active Surveillance Protocols

Active surveillance represents an alternative to immediate surgery for selected patients with low-risk thyroid cancers. This approach involves regular monitoring with physical examination, ultrasound imaging, and sometimes blood tests to detect evidence of cancer progression.

Appropriate candidates for active surveillance include patients with small papillary thyroid cancers (typically less than 1-1.5 centimeters) without evidence of extrathyroidal extension, lymph node involvement, or distant metastases. Patient age, comorbidities, and anxiety levels also influence suitability for active surveillance.

Active surveillance protocols typically involve ultrasound examinations every 6-12 months for the first few years, followed by annual examinations if the cancer remains stable. Triggers for recommending surgery include tumor growth of more than 3 millimeters, development of lymph node metastases, or patient preference for treatment.

Early experience with active surveillance demonstrates that most small thyroid cancers remain stable over time. Progression rates are low, and patients who eventually require surgery do not appear to have worse outcomes compared to those treated immediately. These results support the safety of active surveillance for appropriately selected patients.

Shared Decision-Making

Managing thyroid cancer overdiagnosis requires robust shared decision-making processes that involve patients in treatment decisions. Patients must understand the natural history of their specific cancer type, the risks and benefits of different treatment options, and the uncertainty surrounding optimal management approaches.

Effective shared decision-making for thyroid nodules begins with clear communication about cancer risk. Patients often overestimate the urgency of thyroid cancer treatment based on their understanding of other cancer types. Healthcare providers must explain the unique characteristics of thyroid cancer and the concept that not all cancers require immediate treatment.

Decision aids can help patients understand their options and preferences. These tools present information about treatment outcomes, risks, and quality of life impacts in accessible formats. Studies demonstrate that patients who use decision aids are more likely to choose treatments that align with their values and preferences.

The role of patient anxiety in treatment decisions requires careful consideration. Some patients experience severe anxiety about having untreated cancer, even when the risks are very low. For these patients, treatment may provide psychological benefits that outweigh the physical risks of surgery. However, healthcare providers should avoid assuming that all patients prefer aggressive treatment.

Comparison with Other Cancer Types

Breast Cancer Screening

Thyroid cancer overdiagnosis shares many characteristics with overdiagnosis in breast cancer screening. Both involve detection of cancers that would never have caused symptoms or death during a patient’s lifetime. However, the evidence base for breast cancer screening benefits is much stronger than for thyroid cancer screening.

Randomized controlled trials of mammographic screening demonstrate reductions in breast cancer mortality, albeit smaller than initially hoped. No such evidence exists for thyroid cancer screening, which has never been evaluated in randomized trials. The biological differences between breast and thyroid cancer may explain why screening appears more beneficial for breast cancer.

The approach to managing overdiagnosis differs between these two cancer types. Breast cancer screening programs attempt to reduce overdiagnosis through improved targeting of high-risk populations and longer screening intervals. For thyroid cancer, the focus is on avoiding screening entirely in asymptomatic populations.

Prostate Cancer Screening

Prostate cancer provides perhaps the closest parallel to thyroid cancer in terms of overdiagnosis patterns. Both cancers demonstrate high prevalence in autopsy studies, wide variation in biological behavior, and increased incidence following widespread screening implementation.

The prostate cancer screening experience offers important lessons for thyroid cancer management. Initial enthusiasm for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening led to widespread adoption before evidence of benefit was established. Large randomized trials subsequently demonstrated that screening benefits were much smaller than anticipated, with substantial overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

Current prostate cancer guidelines emphasize shared decision-making and risk stratification rather than routine screening. Similar approaches are being adopted for thyroid cancer, with emphasis on evaluating symptomatic patients while avoiding screening in asymptomatic populations.

Lung Cancer Screening

Lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography represents a more successful screening paradigm. Randomized trials demonstrate clear mortality benefits in high-risk populations, justifying the implementation of screening programs despite some overdiagnosis.

The key difference between lung and thyroid cancer screening lies in the strength of evidence for benefit. Lung cancer screening targets a specific high-risk population (heavy smokers) and has demonstrated mortality reduction in randomized trials. Thyroid cancer screening lacks this evidence base and is often applied to low-risk populations.

The lung cancer screening experience demonstrates that effective screening programs require careful patient selection, standardized protocols, and robust evidence of benefit. These elements are largely absent from current thyroid cancer detection practices.

Challenges and Limitations

Diagnostic Uncertainty

One of the greatest challenges in addressing thyroid cancer overdiagnosis is diagnostic uncertainty. Current diagnostic tools cannot reliably distinguish cancers that require treatment from those that can be safely monitored. This uncertainty creates anxiety for both patients and healthcare providers.

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy, the standard method for evaluating thyroid nodules, has limited ability to predict cancer behavior. The cytological appearance of thyroid cancer does not correlate well with biological aggressiveness. Many cancers that appear concerning under the microscope will never cause clinical problems.

Molecular markers show promise for improving diagnostic accuracy, but their clinical utility remains limited. Most molecular tests focus on diagnosing cancer presence rather than predicting cancer behavior. Future research must prioritize developing tools that can identify cancers requiring treatment rather than simply detecting all cancers present.

The concept of cancer itself contributes to diagnostic uncertainty. Traditional cancer definitions based on histological appearance may not adequately reflect biological behavior. Some experts propose reclassifying low-risk thyroid cancers with alternative terminology that better reflects their indolent nature.

Legal and Medicolegal Concerns

Healthcare providers face challenging medicolegal considerations when managing patients with thyroid nodules. Missing a cancer diagnosis, even one that would never cause harm, can result in malpractice litigation. This defensive medicine environment encourages aggressive diagnostic approaches that contribute to overdiagnosis.

The legal system often fails to account for the nuances of cancer biology and overdiagnosis. Juries may have difficulty understanding how a cancer diagnosis could represent harm rather than benefit. This disconnect between medical evidence and legal expectations creates barriers to implementing evidence-based practice changes.

Professional liability insurance policies and institutional risk management departments may discourage adoption of active surveillance approaches. Healthcare organizations often prefer protocols that minimize legal risk rather than optimizing patient outcomes. These institutional pressures work against efforts to reduce overdiagnosis.

Medical licensing boards and quality assurance programs typically focus on ensuring that cancers are not missed rather than preventing overdiagnosis. Performance metrics often emphasize sensitivity (detecting all cancers) rather than specificity (avoiding unnecessary diagnoses). These measurement approaches inadvertently incentivize overdiagnosis.

Healthcare System Pressures

Multiple healthcare system factors contribute to thyroid cancer overdiagnosis. Financial incentives often favor aggressive diagnostic approaches, as procedures and treatments generate more revenue than watchful waiting. These economic pressures affect both individual healthcare providers and healthcare institutions.

Subspecialty referral patterns can amplify overdiagnosis. Endocrinologists, surgeons, and radiologists may have different perspectives on the appropriate aggressiveness of thyroid nodule evaluation. Patients often receive conflicting recommendations when consulting multiple specialists.

Healthcare quality measures typically emphasize process metrics rather than outcomes. Programs that measure adherence to screening guidelines or time to treatment may inadvertently promote overdiagnosis. Quality measures should focus on appropriate care rather than maximum care.

The medical culture of “doing everything possible” conflicts with evidence-based approaches to overdiagnosis. Healthcare providers may feel pressure to offer all available tests and treatments, even when evidence suggests that less aggressive approaches would be preferable.

Future Directions and Recommendations

Research Priorities

Future research must focus on developing tools to distinguish cancers that require treatment from those that can be safely monitored. Biomarker research should prioritize predicting cancer behavior rather than simply diagnosing cancer presence. Multi-omic approaches combining genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data may provide better prognostic information.

Long-term follow-up studies of patients managed with active surveillance will provide crucial data about the safety of non-operative management. These studies must be large enough and followed long enough to detect rare but important outcomes. International collaboration will be necessary to achieve adequate sample sizes.

Health economic research should quantify the full costs of thyroid cancer overdiagnosis, including direct medical costs, indirect costs from lost productivity, and patient-reported quality of life impacts. These analyses will inform healthcare policy decisions and resource allocation priorities.

Implementation science research is needed to develop effective strategies for reducing thyroid cancer overdiagnosis in clinical practice. Studies should evaluate educational interventions, clinical decision support tools, and policy changes that can modify healthcare provider behavior.

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Professional medical organizations must update clinical practice guidelines to address thyroid cancer overdiagnosis more directly. Current guidelines often focus on optimizing cancer detection rather than preventing overdiagnosis. Future guidelines should emphasize appropriate patient selection for thyroid nodule evaluation.

Guidelines should provide clearer recommendations against screening asymptomatic populations for thyroid cancer. The evidence consistently demonstrates that such screening causes more harm than benefit. Professional organizations must be willing to recommend against interventions that are widely practiced but lack evidence of benefit.

Risk stratification tools should be incorporated into clinical practice guidelines to help healthcare providers identify patients most likely to benefit from thyroid nodule evaluation. These tools should consider patient factors, nodule characteristics, and individual preferences in making management recommendations.

Guidelines should promote shared decision-making approaches that involve patients in management decisions. Standardized decision aids should be developed to help patients understand their options and make informed choices about thyroid nodule evaluation and treatment.

Healthcare Policy Implications

Healthcare policymakers should consider regulatory approaches to reduce thyroid cancer overdiagnosis. Policies that require disclosure of overdiagnosis risks before thyroid imaging or nodule evaluation could help patients make more informed decisions about their care.

Payment policies should be modified to support active surveillance approaches for low-risk thyroid cancers. Current payment structures often favor surgical treatment over watchful waiting. Value-based payment models could incentivize appropriate care rather than maximum care.

Public health campaigns should educate the general population about thyroid cancer overdiagnosis. Many people are unaware that cancer screening can cause harm. Educational initiatives should focus on helping people understand when screening is appropriate and when it should be avoided.

Professional medical education should incorporate training about overdiagnosis and its prevention. Medical students, residents, and practicing physicians need better understanding of cancer biology and the concept that not all diagnosed cancers require treatment.

Technology Development

Artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches may help address thyroid cancer overdiagnosis by improving risk stratification. These technologies could integrate multiple data sources to predict cancer behavior more accurately than current approaches.

Imaging technology development should focus on characterizing cancer aggressiveness rather than simply improving detection sensitivity. Advanced imaging techniques that can predict cancer behavior would be more clinically useful than those that detect smaller cancers.

Decision support tools integrated into electronic health records could help healthcare providers implement evidence-based approaches to thyroid nodule management. These tools could provide real-time guidance about appropriate testing and treatment recommendations.

Telemedicine and remote monitoring technologies may support active surveillance approaches by reducing the burden of frequent follow-up visits. These technologies could make conservative management more convenient for patients while maintaining appropriate monitoring.

Conclusion

Key Takeaways

Thyroid cancer overdiagnosis represents a substantial problem in modern healthcare that causes more harm than benefit. The dramatic increase in thyroid cancer incidence over the past three decades reflects enhanced detection capability rather than increased disease occurrence. Most newly diagnosed thyroid cancers would never have caused symptoms or death if left undetected.

Healthcare providers must understand that early detection is not always beneficial. The biological characteristics of thyroid cancer, particularly small papillary cancers, make them likely candidates for overdiagnosis. Active surveillance represents a safe alternative to immediate surgery for appropriately selected patients with low-risk cancers.

Clinical practice changes are needed to address thyroid cancer overdiagnosis. Healthcare providers should avoid routine screening of asymptomatic patients, implement risk stratification approaches for thyroid nodule evaluation, and engage in robust shared decision-making with patients. Professional guidelines and healthcare policies should support these evidence-based practice changes.

The thyroid cancer overdiagnosis problem cannot be solved by technology alone. While improved diagnostic tests may help distinguish aggressive from indolent cancers, the fundamental issue is the widespread application of screening and diagnostic procedures to populations unlikely to benefit. Cultural changes within healthcare systems are necessary to prioritize appropriate care over maximum care.

Patient education about overdiagnosis is crucial for implementing practice changes. Many patients have unrealistic expectations about cancer screening benefits and may not understand that some cancers do not require treatment. Healthcare providers must communicate these concepts clearly while respecting patient autonomy and preferences.

Frequently Asked Questions:

What is thyroid cancer overdiagnosis?

Thyroid cancer overdiagnosis occurs when screening or incidental imaging detects cancers that would never have caused symptoms, disability, or death during a person’s natural lifespan. These cancers are real cancers under the microscope, but they lack the biological potential to cause harm.

How common is thyroid cancer overdiagnosis?

Research estimates suggest that 50-90% of thyroid cancers diagnosed in women and 70-80% of those diagnosed in men may represent overdiagnosis in countries with high healthcare utilization. The exact percentage varies by population and healthcare system characteristics.

Does this mean thyroid cancer is not dangerous?

Some thyroid cancers are indeed dangerous and require prompt treatment. The challenge is that most newly diagnosed thyroid cancers are small, slow-growing tumors that pose minimal threat to health. Current diagnostic tools cannot reliably distinguish dangerous from harmless thyroid cancers at the time of diagnosis.

Should people avoid thyroid cancer screening?

Yes, medical organizations recommend against routine thyroid cancer screening in asymptomatic people. Screening should be reserved for individuals with specific risk factors such as radiation exposure, family history, or genetic syndromes that predispose to thyroid cancer.

What should someone do if they have been diagnosed with thyroid cancer?

Patients diagnosed with thyroid cancer should discuss their specific situation with qualified healthcare providers. Treatment recommendations depend on cancer size, location, cell type, patient age, and other factors. Active surveillance may be appropriate for small, low-risk cancers, while larger or more aggressive cancers typically require treatment.

How can healthcare providers reduce thyroid cancer overdiagnosis?

Healthcare providers can reduce overdiagnosis by avoiding routine thyroid imaging in asymptomatic patients, implementing evidence-based guidelines for thyroid nodule evaluation, offering active surveillance for appropriate low-risk cancers, and engaging in shared decision-making that helps patients understand their options.

What is active surveillance for thyroid cancer?

Active surveillance involves regular monitoring of small, low-risk thyroid cancers with physical examinations and imaging studies rather than immediate surgery. Research demonstrates that most small thyroid cancers remain stable over time, making this approach safe for appropriately selected patients.

Will active surveillance lead to worse outcomes if cancer spreads?

Studies of active surveillance demonstrate that progression rates are low, and patients who eventually require surgery do not appear to have worse outcomes compared to those treated immediately. Most small thyroid cancers that are appropriate for surveillance never progress to require treatment.

How does thyroid cancer overdiagnosis compare to other types of cancer?

Thyroid cancer overdiagnosis shares similarities with overdiagnosis in prostate and breast cancer. However, thyroid cancer screening lacks the evidence base for mortality reduction that exists for breast cancer screening. The high prevalence of indolent thyroid cancers makes overdiagnosis particularly common in this organ system.

What are the main harms of unnecessary thyroid cancer treatment?

Treatment harms include surgical complications such as nerve damage and hypoparathyroidism, lifelong dependence on hormone replacement therapy, psychological distress from cancer diagnosis, economic costs of treatment and follow-up care, and potential long-term effects of radioactive iodine treatment.

Should incidental thyroid nodules found on imaging be evaluated?

The decision to evaluate incidental thyroid nodules should be individualized based on patient factors and nodule characteristics. Small nodules in older patients or those with limited life expectancy may not warrant further evaluation. Risk stratification guidelines can help determine which incidental nodules merit additional testing.

What role do patient preferences play in managing thyroid nodules?

Patient preferences are crucial in thyroid nodule management decisions. Some patients experience severe anxiety about having untreated cancer, even when risks are very low. Others prefer to avoid unnecessary treatment. Healthcare providers should use shared decision-making approaches that respect patient values and preferences while providing accurate information about risks and benefits.

References:

Ahn, H. S., Kim, H. J., & Welch, H. G. (2014). Korea’s thyroid-cancer “epidemic”—screening ultrasound’s impact. New England Journal of Medicine, 371(19), 1765-1767.

Brito, J. P., Ito, Y., Miyauchi, A., & Tuttle, R. M. (2016). A clinical framework to facilitate risk stratification when considering an active surveillance alternative to immediate biopsy and surgery in papillary microcarcinoma. Thyroid, 26(1), 144-149.

Davies, L., & Welch, H. G. (2006). Increasing incidence of thyroid cancer in the United States, 1973-2002. JAMA, 295(18), 2164-2167.

Davies, L., & Welch, H. G. (2014). Current thyroid cancer trends in the United States. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, 140(4), 317-322.

Grodski, S., Brown, T., Sidhu, S., Gill, A., Robinson, B., Learoyd, D., … & Delbridge, L. (2013). Increasing incidence of thyroid cancer is due to increased pathologic detection. Surgery, 154(6), 1365-1371.

Haugen, B. R., Alexander, E. K., Bible, K. C., Doherty, G. M., Mandel, S. J., Nikiforov, Y. E., … & Wartofsky, L. (2016). 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid, 26(1), 1-133.

Ito, Y., Miyauchi, A., Kihara, M., Higashiyama, T., Kobayashi, K., & Miya, A. (2014). Patient age is significantly related to the progression of papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid under observation. Thyroid, 24(1), 27-34.

Kent, W. D., Hall, S. F., Isotalo, P. A., Houlden, R. L., George, R. L., & Groome, P. A. (2007). Increased incidence of differentiated thyroid carcinoma and detection of subclinical disease. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 177(11), 1357-1361.

Lim, H., Devesa, S. S., Sosa, J. A., Check, D., & Kitahara, C. M. (2017). Trends in thyroid cancer incidence and mortality in the United States, 1974-2013. JAMA, 317(13), 1338-1348.

Miyauchi, A., Kudo, T., Miya, A., Kobayashi, K., Ito, Y., Takamura, Y., … & Higashiyama, T. (2011). Prognostic impact of serum thyroglobulin doubling-time under thyrotropin suppression in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma who underwent total thyroidectomy. Thyroid, 21(7), 707-716.

Morris, L. G., Sikora, A. G., Tosteson, T. D., & Davies, L. (2013). The increasing incidence of thyroid cancer: the influence of access to care. Thyroid, 23(7), 885-891.

Nickel, B., Brito, J. P., Barratt, A., Jordan, S., Moynihan, R., & McCaffery, K. (2018). Clinicians’ views on management and terminology for papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a qualitative study. Thyroid, 28(9), 1134-1142.

Reiners, C., Wegscheider, K., Schicha, H., Theissen, P., Vaupel, R., Wrbitzky, R., & Schumm-Draeger, P. M. (2004). Prevalence of thyroid disorders in the working population of Germany: ultrasonography screening in 96,278 unselected employees. Thyroid, 14(11), 926-932.

Tuttle, R. M., Fagin, J. A., Minkowitz, G., Wong, R. J., Roman, B., Patel, S., … & Shaha, A. R. (2017). Natural history and tumor volume kinetics of papillary thyroid cancers during active surveillance. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, 143(10), 1015-1020.

Vaccarella, S., Franceschi, S., Bray, F., Wild, C. P., Plummer, M., & Dal Maso, L. (2016). Worldwide thyroid-cancer epidemic? The increasing impact of overdiagnosis. New England Journal of Medicine, 375(7), 614-617.

Welch, H. G., & Black, W. C. (2010). Overdiagnosis in cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 102(9), 605-613.

Welch, H. G., Kramer, B. S., & Black, W. C. (2019). Epidemiologic signatures in cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 381(14), 1378-1386.

Video Section

Check out our extensive video library (see channel for our latest videos)

Recent Articles