Comorbid Insomnia New Research Reveals Bidirectional Mental Health Links

Introduction

Comorbid insomnia represents a substantial and often underrecognized public health challenge, affecting an estimated 25 million individuals in the United States each year and contributing to approximately $100 billion in annual healthcare expenditures. Sleep disturbances occur in up to one third of the population, while chronic insomnia disorder affects roughly 20 percent of adults. Beyond its immediate impact on sleep quality, insomnia is increasingly understood as a multidimensional condition with far reaching consequences for psychological health, cognitive performance, cardiometabolic function, and overall quality of life.

The relationship between sleep disruption and mental health is not merely associative but reflects a complex bidirectional interaction. Neurobiological evidence suggests that insomnia contributes to dysregulation across several physiological systems, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, inflammatory signaling pathways, and neurotransmitter networks involved in mood regulation. Persistent hyperarousal, altered circadian rhythms, and impaired emotional processing further reinforce vulnerability to psychiatric illness. At the same time, mental health disorders can exacerbate sleep fragmentation, prolong sleep latency, and reduce restorative sleep, thereby perpetuating a self sustaining cycle of dysfunction.

Epidemiological studies highlight the magnitude of this relationship. Individuals diagnosed with insomnia demonstrate markedly elevated risks for developing psychiatric disorders, with approximately tenfold higher likelihood of major depressive episodes and a seventeenfold increased risk of anxiety disorders compared with individuals without chronic sleep disruption. These associations are highly relevant in clinical practice, where more than 70 percent of patients report insomnia symptoms during initial healthcare encounters. Among patients with documented sleep disturbances, the prevalence of anxiety and depression has been reported at 87.1 percent and 88.0 percent, respectively. In populations already experiencing depression or anxiety, insomnia symptoms frequently exceed an 80 percent prevalence rate. Collectively, these findings support a conceptual shift in which insomnia is viewed not solely as a secondary manifestation of psychiatric disease but also as an independent and potentially causal contributor to the onset and progression of mental and medical disorders.

Advances in neuroimaging and sleep physiology have further clarified the mechanisms underlying comorbid insomnia. Functional imaging studies reveal increased metabolic activity in wake promoting brain regions during periods that typically favor sleep, suggesting an inability to appropriately downregulate cortical arousal. Alterations in gamma aminobutyric acid signaling, heightened sympathetic activation, and impaired glymphatic clearance during sleep have also been proposed as contributors to neurocognitive decline and emotional dysregulation. These mechanistic insights underscore the importance of early identification and targeted treatment.

Assessment strategies have similarly evolved. Comprehensive evaluation now emphasizes standardized diagnostic criteria, structured sleep histories, actigraphy, and when indicated, polysomnography to exclude coexisting sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea or periodic limb movement disorder. Screening for psychiatric comorbidity is essential, as failure to address underlying mood or anxiety disorders often results in incomplete therapeutic response.

Evidence based management increasingly favors nonpharmacologic interventions as first line therapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia remains the gold standard due to its durable efficacy and favorable safety profile. Pharmacologic treatments, including nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics, melatonin receptor agonists, and dual orexin receptor antagonists, may serve as adjunctive options when carefully selected and monitored. Integrated care models that simultaneously address insomnia and coexisting psychiatric conditions demonstrate improved outcomes compared with sequential treatment approaches. For clinicians, recognizing insomnia as a modifiable risk factor offers an opportunity to reduce psychiatric morbidity and enhance long term patient functioning.

While sleep medicine continues to advance, another transformative area of biomedical innovation is emerging in transfusion science: the development of artificial blood. The concept has progressed from early plasma expanders toward sophisticated oxygen carrying solutions engineered to replicate key physiologic functions of erythrocytes. These products are designed to transport oxygen and carbon dioxide efficiently while preserving oncotic pressure and supporting hemodynamic stability. Unlike conventional blood products, artificial alternatives offer theoretical advantages such as extended shelf life, universal compatibility without the need for crossmatching, and elimination of transfusion transmitted infections.

Taken together, the evolving science of comorbid insomnia illustrates the broader trajectory of modern medicine toward earlier recognition of disease, mechanistically informed therapies, and innovative technological solutions. For healthcare professionals, staying informed about these developments is essential for optimizing patient care, improving system efficiency, and preparing for a future in which interdisciplinary advances increasingly shape clinical decision making.

Redefining Comorbid Insomnia in Modern Psychiatry

The historical classification of insomnia has undergone notable evolution in recent psychiatric diagnostic frameworks, moving away from overly simplistic models toward a more nuanced understanding of sleep disturbances in mental health contexts.

ICSD-3 and DSM-5 Classification Changes

The Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) and the Third Edition of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3) represent a paradigm shift in how insomnia is conceptualized clinically. Previously, the DSM-IV distinguished between primary and secondary insomnia, implying a hierarchical relationship where insomnia was often viewed merely as a symptom of another disorder [1]. This distinction has been deliberately removed from both classification systems, reflecting an essential reconceptualization of sleep disturbances [2].

Instead of secondary classification, DSM-5 now employs the term “insomnia disorder” with specifiers to indicate the presence of comorbidities, effectively removing assumptions about causality [3]. This modification acknowledges that insomnia and psychiatric disorders share a bidirectional relationship, functioning as risk factors for each other [3]. According to Michael Sateia, editor of ICSD-3, “Insomnia is insomnia is insomnia” – emphasizing its status as a disorder unto itself requiring independent clinical attention [4].

What is Comorbid Insomnia? Clinical Criteria and Duration

The term “comorbid insomnia” emerged from the 2005 National Institutes of Health’s State-of-the-Science Conference to describe insomnia occurring alongside medical or psychiatric conditions [2]. Current diagnostic criteria require several key elements for an insomnia diagnosis: persistent sleep difficulty despite adequate opportunity for sleep, associated daytime dysfunction, and specific frequency and duration parameters [2].

DSM-5 criteria specify that an individual must experience dissatisfaction with sleep quantity or quality associated with difficulty initiating sleep, maintaining sleep, or early morning awakening with inability to return to sleep [5]. These difficulties must occur at least three nights per week for at least three months – an increase from the one-month duration previously required [6]. Additionally, symptoms must cause clinically significant distress or functional impairment [5].

Notably, the sleep problems should not be better explained by another sleep disorder, though patients may simultaneously experience multiple sleep disorders – such as comorbid insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea (COMISA) [2]. Consequently, thorough clinical assessment becomes crucial as the diagnosis directly impacts treatment approaches [2].

Prevalence in Psychiatric Populations

Insomnia symptoms appear in approximately 50-80% of patients with psychiatric disorders [7], substantially higher than the 9-12% prevalence observed in the general adult population [7]. This elevated rate varies by condition and treatment setting. A recent study found DSM-5 insomnia disorder in 31.8% of psychiatric patients, with affected individuals showing markedly greater functional impairment than those without insomnia [7].

The prevalence grows even higher in more acute settings – one study of hospitalized psychiatric patients found 67.4% screened positive for insomnia according to the Insomnia Severity Index [7]. Another investigation reported an 80.5% insomnia prevalence among psychiatric outpatients at a tertiary care hospital [7].

Across specific conditions, insomnia appears in over 90% of patients with major depressive disorder [7]. It constitutes a central diagnostic criterion in both depressive and manic episodes of bipolar disorder, as well as in generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and schizophrenia [7].

Despite these high rates, clinical attention to insomnia often remains inadequate. One striking Norwegian study found that among 42,507 mental health center patients, only 34 (0.08%) received an insomnia diagnosis, even though approximately 40% reported severe sleep disturbances and 22% considered this one of their most prominent problems [2].

Neurobiological Mechanisms Linking Sleep and Mental Health

Recent neuroimaging and molecular studies have revealed intricate brain circuits connecting sleep disruption with psychiatric symptoms, offering a deeper understanding of why patients with comorbid insomnia often experience worsening mental health outcomes.

Hyperarousal and the Role of Orexin Signaling

Orexin (hypocretin) neurons located in the lateral hypothalamus serve as critical regulators of arousal and wakefulness. These neurons exert their influence by tonically exciting various arousal systems, including monoaminergic and cholinergic pathways [4]. The hyperarousal state observed in comorbid insomnia correlates with elevated orexin system activity, creating a neurobiological environment that interferes with normal sleep initiation and maintenance [8]. Patients with chronic insomnia exhibit markedly elevated plasma orexin-A levels, with these elevations worsening in proportion to both the duration and self-reported severity of the disorder [7].

In contrast, narcolepsy—characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness and sleep attacks—results from insufficient orexin signaling due to the destruction of orexin-producing neurons [9]. This opposing condition highlights orexin’s central role in stabilizing wakefulness. Functionally, orexin neurons precede muscle movement and arousals during transitions from REM sleep to wakefulness [7], thus contributing to the fragmented sleep patterns frequently observed in patients with comorbid psychiatric conditions.

Consequently, dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORAs) have emerged as mechanistically distinct options for treating insomnia, functioning without the GABAergic sedation common to traditional hypnotics [4]. Unlike benzodiazepines and Z-drugs, these medications appear devoid of dependence and tolerance-inducing effects, offering a promising approach for longer-term treatment [8].

GABAergic Inhibition and Sleep Onset

GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) functions as the principal inhibitory neurotransmitter governing sleep initiation and maintenance. Current research indicates reduced GABAergic tone in patients with insomnia and related hyperarousal states [4]. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies have detected lower cortical GABA levels in chronic insomnia patients, aligning with their difficulty down-regulating arousal at night [4].

The GABAergic system counterbalances excitatory neurotransmitters that increase arousal during sleep, including glutamate, noradrenaline, serotonin, acetylcholine, orexin, and dopamine [6]. This balance proves essential for proper sleep regulation, with studies showing that GABA appears in the ventrolateral preoptic (VLP) nucleus of the hypothalamus to inhibit ascending arousal activity during normal sleep transitions [6].

Most conventional sleep medications (benzodiazepines, zolpidem, zaleplon, and eszopiclone) act as positive allosteric modulators at GABA-A receptors [4]. However, these agents shift non-REM sleep microarchitecture toward lighter stage N2 sleep, highlighting a tradeoff between sedation and physiological sleep depth [4]. This alteration may explain why some patients with comorbid insomnia report continued daytime symptoms despite pharmacologically induced sleep.

Monoaminergic Dysregulation in Depression and Psychosis

Monoaminergic neurotransmission abnormalities provide another crucial link between sleep disruption and psychiatric symptoms. Foundational accounts emphasize reduced serotonergic tone as a shared substrate for both depression and its associated sleep abnormalities [4]. One of the most robust neurophysiological markers of depression involves REM sleep changes—specifically higher REM density in unmedicated patients with major depressive disorder compared to healthy controls [4]. Moreover, this REM density increase has been linked to greater depressive symptom severity in population-based samples.

In psychosis, dopamine plays a central role connecting sleep disruption with psychotic symptoms. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia postulates that hyperactivity in dopaminergic pathways underlies symptom development [5]. D2 receptor agonists bolster alertness while simultaneously diminishing both slow-wave and REM sleep [5], suggesting pathways linking dopaminergic alterations with sleep disturbances and schizophrenia symptoms.

Beyond neurotransmitter activity, structural brain abnormalities also contribute to this relationship. The thalamus—implicated in both sleep regulation and psychosis—exhibits early volume reduction in psychotic disorders that worsens as the illness progresses [5]. Sleep deprivation further affects psychosis risk by impairing synaptic transmission, potentially through cholinergic depletion that increases vulnerability to hallucinations [5].

These neurobiological mechanisms illustrate how sleep and mental health form an interconnected system where disruption in one domain inevitably affects the other, explaining why effective treatment often requires addressing both components simultaneously.

Insomnia and Depression: A Bidirectional Relationship

The relationship between sleep disorders and mood disturbances extends beyond simple comorbidity, forming a complex interplay where each condition actively influences the other. Patients with depression almost inevitably exhibit sleep abnormalities, including shortened REM latency and decreased delta power during non-REM sleep [10]. Likewise, insufficient sleep creates stress that deteriorates mental health, establishing a cycle where depression contributes to sleep disturbances and vice versa [10].

Insomnia as a Predictor of Major Depressive Disorder

Sleep disturbances represent one of the most powerful predictors of future depressive episodes [7]. Non-depressed individuals with insomnia face approximately twice the risk of developing depression compared to those without sleep difficulties, according to meta-analysis data [1]. This relationship holds true regardless of whether sleep problems occur independently or alongside other conditions [7]. Indeed, insomnia can herald depression onset and often persists into remission or recovery, even after adequate treatment [1].

The predictive power of sleep disruption remains remarkably stable over time—insomnia in people indicates an elevated depression risk that persists for at least 30 years [2]. Among psychiatric populations, this connection becomes especially pronounced, with up to 90% of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) reporting sleep disturbances [2]. Conversely, individuals experiencing insomnia incur a tenfold higher risk of depression, while 75% of those with depression report sleep difficulties [3].

Essentially, this bidirectional relationship manifests through observable mechanisms: depression alters sleep architecture, whereas poor sleep quality reduces stress resilience and emotional regulation capacity. Recent animal studies further support this bidirectional connection, offering promising avenues for identifying neural circuits linking stress, sleep disturbance, and depression [11].

Impact on Suicidal Ideation and Relapse Risk

Beyond predicting depression onset, insomnia plays a crucial role in determining illness trajectory and suicide risk. Symptoms of insomnia emerge as strong predictors of decreased remission rates and higher relapse risk in depression [7]. The comorbidity between insomnia and MDD produces poorer outcomes—patients with sleep disturbances show greater depression severity [7], lower remission rates [7], and substantially higher risk for relapse [7].

Particularly concerning, insomnia now appears as an independent risk factor for suicide, suicidal thoughts, behaviors, and non-suicidal self-injury across all age groups [8]. More than 60 separate research reports from the Americas, Europe, and Asia confirm this connection with relative risks around 2.0 [8]. In studies of veteran suicide deaths, insomnia was documented in nearly half of the last doctor’s visits preceding death [8].

The duration of sleep problems proves equally important—persistent sleep difficulties correlate with suicidal ideation among depressed patients even after remission across four years [8]. This relationship persists after adjusting for mood disorder severity [8], identifying insomnia as a modifiable risk factor alongside hopelessness [8]. CBT-I treatment has demonstrated significant decreases in suicidal ideation among those with baseline suicidal thoughts, with remarkably large effect sizes (d = 1.83) [7].

CBTi Outcomes in Depression Insomnia Cases

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) offers promise for addressing both conditions simultaneously. Among patients with comorbid insomnia and MDD, CBT-I effectively treats sleep symptoms [7] and produces remarkable improvements in depression [7]. Studies reveal that improvements in insomnia early in treatment predict the trajectory of depression response [7].

Analysis from the TRIAD study identified three response patterns following CBT-I for comorbid depression and insomnia: Partial-Responders, Initial-Responders, and Optimal-Responders [7]. Patients who achieved the greatest and most rapid reductions in insomnia severity, sleep effort, and unhelpful beliefs about sleep were most likely to be categorized as Optimal-Responders (13.5% of sample), maintaining minimal depression even at two-year follow-up [7].

Digital CBT-I demonstrates similar effectiveness—improvements in insomnia symptoms at mid-intervention mediated 87% of the effects on depressive symptoms post-intervention [7]. Remarkably, baseline depression severity does not necessarily impair CBT-I outcomes; group therapy works equally well among those with high versus low depression severity [7]. Nevertheless, while treatment reduces symptoms proportionally across groups, those with greater baseline depression typically maintain relatively higher absolute insomnia severity throughout treatment [7].

Overall, targeting the tendency to ruminate in response to fatigue emerges as particularly important during CBT-I, as this process directly contributes to depression improvement [12].

Sleep Disruption in Psychotic Disorders

Sleep disruptions represent hallmark features of schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, with up to 80% of patients experiencing sleep abnormalities [6]. Far from being mere secondary symptoms, these disturbances likely play a causal role in both symptom development and exacerbation, creating additional comorbid insomnia challenges that require clinical attention.

Circadian Rhythm Dysfunction in Schizophrenia

Disruption of the sleep-wake cycle constitutes a fundamental aspect of schizophrenia pathophysiology. Research utilizing wrist actigraphy and melatonin profiling has revealed that all patients with schizophrenia experience some degree of circadian misalignment [13]. Half demonstrate severe circadian disruptions characterized by:

- Phase-advanced or phase-delayed sleep periods

- Non-24-hour rhythms unentrained by normal light-dark cycles

- Highly irregular and fragmented sleep patterns [13]

At the molecular level, alterations in rhythmic expression of core clock genes indicate a dysfunctional circadian system [6]. Genetic association studies have demonstrated that mutations in several clock genes correlate with increased schizophrenia risk [6]. Research published in Nature Communications found that patients with schizophrenia exhibit “a very different set of diurnally rhythmic genes and a different rhythmic pattern in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex compared to control subjects” [14], suggesting fundamental disruptions in cellular timekeeping mechanisms.

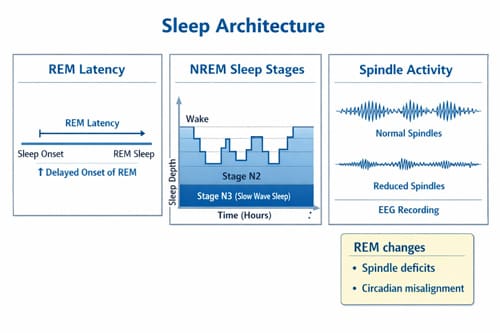

Polysomnography Findings: REM and Sleep Spindles

Objective polysomnographic evaluations reveal distinctive sleep architecture abnormalities in psychotic disorders. Initially, Caldwell et al. documented reduced slow-wave sleep in patients with schizophrenia, a finding subsequently confirmed in both chronic and early-course illness [4]. Beyond these changes, REM abnormalities—including both increases [4] and decreases [4] in REM duration plus reduced REM latency [4]—frequently occur.

Recently, research has focused on sleep-specific EEG oscillations, primarily sleep spindles. Multiple studies document consistent deficits in spindle parameters (density, amplitude, and duration) across psychotic disorders [5]. These reductions primarily localize to frontal-parietal and prefrontal regions [4] and persist regardless of medication status [4]. In first-episode psychosis, reduced spindle duration and density correlate with negative symptom severity [15].

A 2022 meta-analysis reported that spindle deficits yield large effect sizes and appear associated with disease progression [5]. Furthermore, these abnormalities serve as potential neurophysiological biomarkers that could monitor the course of psychotic illness [5].

Melatonin and Antipsychotic Interventions

Individuals with schizophrenia typically exhibit decreased endogenous melatonin secretion, even when sleep quantity and quality improve with antipsychotic treatment [16]. Effectively, this pattern suggests persistent circadian dysregulation despite symptomatic improvement.

Melatonin supplementation offers promising therapeutic potential through both its chronobiotic action (entraining circadian rhythms) and direct sleep-promoting effects [17]. Clinical trials demonstrate that melatonin administration alongside antipsychotic medication improves sleep measures including efficiency and duration [6]. Animal studies further suggest melatonin may reduce schizophrenia-like behaviors, potentially addressing cognitive impairment and social withdrawal [6].

Traditional antipsychotics generally improve sleep quality, with second-generation sedating agents (quetiapine, olanzapine, risperidone) demonstrating particular efficacy [6]. Notably, improvements in sleep parameters often correlate with reduction in negative symptoms [6]. Melatonin may offer additional benefits, especially for tardive dyskinesia, where a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study demonstrated clinically meaningful improvement [18].

For treatment-resistant comorbid insomnia in psychosis, a graduated approach typically begins with sleep hygiene interventions, progresses through cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), then considers pharmacological options including melatonin before stronger sedative-hypnotics [15].

Anxiety Disorders and Sleep Fragmentation

Anxiety disorders disrupt sleep architecture through multiple pathways, creating distinct patterns of fragmentation that exacerbate both conditions. These disturbances represent more than mere symptoms—they function as core components of anxiety pathophysiology with extensive bidirectional influences.

Sleep Latency and WASO in GAD and Panic Disorder

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) primarily manifests as sleep maintenance insomnia, with secondary difficulties in sleep initiation. In GAD patients, polysomnography reveals increased wake after sleep onset (WASO), decreased sleep efficiency, and reduced total sleep time compared to healthy controls [9]. Multiple investigations demonstrate that approximately 60-70% of GAD patients report insomnia complaints, with symptom severity paralleling anxiety intensity [19]. This suggests insomnia represents a fundamental aspect of GAD rather than a mere associated feature.

Panic disorder exhibits distinct sleep disruption patterns. Subjective sleep complaints, primarily insomnia, affect up to 77% of patients with panic disorder, with 68% reporting difficulties falling asleep [19]. Objectively, polysomnography confirms these perceptions, showing impaired sleep initiation and maintenance characterized by:

- Increased sleep latency and wake time after sleep onset

- Reduced sleep efficiency and total sleep time

- Inconsistent alterations in NREM and REM architecture [19]

Most notably, 20-45% of panic disorder patients experience recurrent nocturnal panic attacks, differentiating this condition from other anxiety disorders [19]. These episodes typically occur during transitions from stage 2 to stage 3 sleep, contrasting with sleep terrors (stage 4) and nightmares (REM sleep).

Social Anxiety and Sleep Quality Correlation

Sleep quality and social anxiety maintain robust connections across both clinical and non-clinical populations. Research indicates individuals with heightened social interaction anxiety frequently demonstrate poor sleep quality [20]. Among adolescents—a particularly vulnerable population—social anxiety correlates with specific sleep disturbances including bedtime resistance, night waking, nightmares, and insomnia symptoms [20].

This relationship operates bidirectionally. Sleep deprivation amplifies anxiety-related neural activity, particularly in the amygdala [2]. Consequently, sleep-deprived individuals become more wary and hostile toward others, actively avoiding social interaction [21]. In clinical settings, the behavioral manifestations include reduced exploratory behavior and increased social withdrawal [22].

Recent animal models clarify this connection, demonstrating that sleep fragmentation increases anxiety-like behavior through elevated oxidative stress in the hippocampus, thalamus, and cortex [2]. This neurobiological mechanism helps explain why duration of sleep fragmentation strongly predicts anxiety severity.

Nocturnal Panic and Sleep Apnea Overlap

Nocturnal panic and obstructive sleep apnea share striking symptom overlap yet require different interventions. Nocturnal panic refers to waking from sleep in a state of panic, distinguishable from nightmares or environmental stimuli-induced arousals [19]. These episodes typically feature autonomic symptoms—palpitations, sweating, shortness of breath—alongside marked psychic anxiety and fear of dying [19].

Evidence indicates a bidirectional relationship between sleep apnea and panic disorder. Sleep apnea patients face a substantially higher risk for future panic disorder development (hazard ratio: 2.17) [1]. In one study tracking patients for nearly four years, sleep apnea cohorts showed panic disorder incidence rates of 33.86 per 10,000 person-years compared to 10.73 in control groups [1].

This association stems from several mechanisms. Sleep fragmentation from apneic episodes creates frequent arousals, often accompanied by feelings of choking or suffocation [23]. These experiences closely mimic panic symptoms, potentially conditioning fear responses to sleep itself. Furthermore, intermittent hypoxemia may facilitate oxidative stress-related nervous system injury [1], increasing vulnerability to panic episodes.

Treatment approaches must address both conditions. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy for sleep apnea patients with comorbid panic disorder decreases panic attacks and reduces benzodiazepine usage [1]. Cognitive-behavioral approaches provide additional benefits, particularly for patients developing conditioned fear of sleep.

Insomnia in ADHD and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) presents unique challenges in sleep regulation, with insomnia representing a core clinical feature rather than merely a secondary symptom. Sleep disturbances affect up to 82.6% of individuals with ADHD compared to 36.5% of control groups [8]. These disruptions manifest as difficulties initiating or maintaining sleep, with morning wakefulness problems strongly associated with ADHD diagnosis.

Delayed Sleep Phase in Children with ADHD

Delayed sleep phase syndrome (DSPS) occurs frequently in both pediatric and adult ADHD populations. This circadian rhythm disorder involves a persistent shift in the sleep-wake cycle, resulting in difficulty falling asleep at conventional times and extreme morning awakening challenges [24]. The underlying mechanisms involve both altered endogenous rhythmicity and executive functioning difficulties that maintain irregular sleep habits [8].

For adolescents with ADHD, this problem intensifies as normative adolescent circadian shifts compound existing rhythm disturbances. Up to 75% of adults with childhood-onset ADHD exhibit delayed circadian phase, with biological markers including melatonin onset and cortisol rhythms occurring approximately 1.5 hours later than in neurotypical individuals [25]. Uniquely, while neurotypical individuals typically shift back toward morningness in early adulthood, those with ADHD often maintain delayed phases chronically [25].

Stimulant Medication and Sleep Onset Latency

Stimulant medications present a paradoxical relationship with sleep in ADHD. Insomnia ranks among the most common adverse events associated with these treatments [7], yet the relationship proves complex. Studies using actigraphy to measure sleep onset latency (SOL) found that methylphenidate increased SOL from approximately 40 minutes with placebo to 60-70 minutes on medication [7]. Meta-analysis confirms these findings, indicating that stimulants produce longer sleep latencies (effect size 0.54) and shorter total sleep duration (effect size -0.59) [26].

Individual responses vary considerably—higher doses correlate with increased insomnia risk, primarily affecting younger and smaller patients [7]. Contemporary extended-release formulations show similar sleep impacts, yet some patients report improved sleep on low medication doses, potentially by reducing rebound hyperactivity as medication wears off [7].

Behavioral Interventions vs Pharmacological Approaches

Non-pharmacological interventions offer distinct advantages for managing comorbid insomnia in ADHD. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-i) demonstrates efficacy as first-line treatment, even when insomnia occurs alongside psychiatric conditions [8]. For children, tailored behavioral sleep interventions yield moderate improvement in sleep disturbances (effect size -0.49) with moderate certainty of evidence [12].

Pharmacologically, melatonin supplementation effectively addresses delayed sleep phase and sleep onset insomnia in pediatric ADHD [8], increasing total sleep time by approximately 30 minutes after four weeks [27]. Unlike traditional hypnotics, melatonin targets circadian mechanisms directly relevant to ADHD’s sleep pathophysiology [24].

Importantly, bright light therapy shows promise for adults with ADHD, directly addressing the circadian misalignment underlying many sleep complaints [8]. This approach aligns with research demonstrating inverse relationships between solar intensity and ADHD prevalence, with solar exposure explaining up to 57% of variance in adult ADHD prevalence rates across geographical regions [25].

Substance Use and Sleep Dysregulation

Many patients with sleep disorders self-medicate with substances to induce sleep, creating a cycle of dependence that ultimately worsens both conditions. This bidirectional relationship between substance use and sleep dysregulation presents unique challenges for clinicians treating comorbid insomnia.

Alcohol as a Sleep Aid and Risk of Dependence

Approximately 14.3% of individuals report using alcohol to aid sleep [28]. Those with more severe insomnia face increased odds of using alcohol as a sleep aid (OR=1.03), as do patients with PTSD (OR=2.11) [28]. Although alcohol induces drowsiness through its effects on GABA receptors, it fundamentally disrupts sleep architecture by:

- Increasing nighttime awakenings and sleep fragmentation

- Reducing REM sleep and causing fragmented, low-quality sleep

- Worsening snoring and sleep apnea by relaxing throat muscles [29]

Concerningly, alcohol use for sleep correlates with substantially increased odds of daily drinking (OR=8.43) [28]. As tolerance develops to alcohol’s sedative effects, larger amounts become necessary to achieve sleep onset, establishing a vicious cycle. Unfortunately, this pattern often leads patients to combine alcohol with sleep medications—those using alcohol for sleep showed 79% higher odds of using prescription sleep aids [28].

Persistent Insomnia Post-Abstinence

Sleep dysfunction may persist up to two years into recovery from alcohol use disorder [10]. This extended dysregulation stems from neuroadaptations in sleep-wake systems. Chronic substance exposure upregulates orexin neurons in the lateral hypothalamus, creating a hyperarousal state that persists well beyond acute withdrawal [11].

For stimulant users, pathological sleepiness (latencies <5 minutes) appears during early discontinuation days [3]. Even after 14 days of abstinence, nocturnal sleep disturbances and REM rebound remain evident [3]. These persistent sleep disruptions drive drug craving and contribute to impulsivity and relapse risk [11].

Gabapentin and Trazodone in Dual Diagnosis Cases

For patients with comorbid substance use and insomnia, traditional sedative-hypnotics pose major risks due to their abuse potential [30]. Hence, medications like gabapentin and trazodone have emerged as safer alternatives.

In a comparative study of alcohol-dependent patients with persistent insomnia after at least four weeks of abstinence, both gabapentin and trazodone produced meaningful sleep improvements [30]. Nonetheless, gabapentin demonstrated superior efficacy—patients receiving gabapentin reported less initial insomnia and morning fatigue than trazodone-treated individuals [30]. Gabapentin-treated patients were less likely to awaken feeling tired and worn out [30].

Both medications demonstrated good tolerability, with low dropout rates and no notable differences between groups [30]. Their contrasting mechanisms—gabapentin through GABA enhancement and trazodone via serotonergic effects—offer complementary approaches for addressing the complex interaction between substance use and comorbid insomnia.

Clinical Screening and Treatment Recommendations

Effective management of comorbid insomnia requires validated assessment tools and evidence-based treatment selection. Clinical expertise must guide decision-making, balancing patient preferences with proven interventions.

Use of ISI, ESS, and Berlin Questionnaire

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), a 7-item self-report questionnaire, effectively evaluates global insomnia severity with scores ≥15 indicating clinically significant insomnia [6]. Alongside, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) quantifies subjective daytime sleepiness across eight situations; scores >10 suggest excessive sleepiness [6]. For sleep-disordered breathing assessment, the Berlin Questionnaire (BQ) identifies risk through 11 questions across three categories: snoring behavior, daytime fatigue, and obesity/hypertension history [13]. Nonetheless, the STOP-Bang questionnaire demonstrates superior sensitivity for detecting obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) across different age groups, genders, and comorbidities [14].

CBTi vs Pharmacotherapy: When to Use What

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine strongly recommends multicomponent cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) as first-line treatment [31]. Meanwhile, other approaches including stimulus control, sleep restriction, and relaxation therapy receive conditional recommendations [31]. For pharmacotherapy, clinical evidence shows CBT-I yielding comparable short-term but superior long-term outcomes versus medications [32]. Long-term studies consistently favor CBT-I over benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepines for improving sleep efficiency [32]. Moreover, patients report greater satisfaction with CBT-I than zopiclone on standardized questionnaires [32].

Internet-Based CBTi for Underserved Populations

Digital CBT-I platforms increase accessibility for populations with limited resources. Internet-delivered programs like Sleep Healthy Using the Internet (SHUTi) demonstrate substantial efficacy—nearly half of older adults receiving SHUTi no longer experienced insomnia at one-year follow-up [33]. Similarly, culturally-tailored adaptations show promise for minority populations traditionally underrepresented in sleep medicine [34]. For psychiatric patients with limited healthcare access, computer-based CBT-I implemented in community mental health centers produced marked improvements on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [5].

Conclusion

Comorbid insomnia stands as a prevalent yet often undertreated condition with far-reaching implications across psychiatric practice. Throughout this examination of recent research, the complex bidirectional relationship between sleep disturbances and mental health conditions has emerged as a central theme. Rather than viewing insomnia as merely symptomatic of psychiatric disorders, contemporary evidence supports its role as both contributor to and consequence of various mental health conditions.

The neurobiological underpinnings—from orexin signaling abnormalities to GABAergic inhibition deficits—help explain why sleep disruption exacerbates psychiatric symptoms while psychiatric conditions simultaneously disrupt sleep architecture. This bidirectional interaction creates self-perpetuating cycles that require targeted intervention addressing both components.

Sleep disturbances predict depression onset with remarkable consistency, while insomnia treatment substantially reduces both depression severity and suicidal ideation. Likewise, the distinct patterns of sleep fragmentation in anxiety disorders reflect core pathophysiological processes rather than secondary symptoms. For patients with psychotic disorders, circadian rhythm dysfunction and sleep spindle abnormalities represent potential biomarkers with implications for both diagnosis and treatment.

The unique challenges of ADHD-related sleep disruption, particularly delayed sleep phase and stimulant medication effects, necessitate specialized approaches combining behavioral interventions with careful medication management. Additionally, substance use often begins as self-medication for sleep difficulties yet ultimately worsens both conditions through persistent neuroadaptations that extend well beyond acute withdrawal.

Clinical management of comorbid insomnia requires thoughtful screening using validated tools such as the Insomnia Severity Index alongside evidence-based treatment selection. While cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) remains the first-line recommendation with superior long-term outcomes compared to medications, digital delivery platforms now extend this effective treatment to previously underserved populations.

Moving forward, addressing sleep disturbances must become standard practice in psychiatric care rather than an afterthought. Clinicians who recognize and treat the bidirectional relationship between sleep and mental health ultimately provide more effective care for their patients. Through this integrated approach, practitioners can interrupt self-reinforcing cycles of sleep disruption and psychiatric symptoms, potentially altering disease trajectories and improving long-term outcomes across diverse psychiatric conditions.

Key Takeaways

Understanding the bidirectional relationship between sleep and mental health is crucial for effective psychiatric treatment, as these conditions actively influence each other rather than existing as separate issues.

- Insomnia predicts psychiatric disorders: People with insomnia face 10x higher depression risk and 17x higher anxiety risk compared to good sleepers.

- Sleep disruption drives suicide risk: Insomnia independently increases suicide risk across all ages, making it a critical modifiable risk factor in mental health care.

- CBT-I outperforms medication long-term: Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia shows superior lasting benefits compared to sleep medications for treating comorbid conditions.

- Neurobiological mechanisms explain the connection: Orexin hyperarousal, GABA deficits, and monoamine dysregulation create shared pathways linking sleep disturbances with psychiatric symptoms.

- Screen and treat sleep systematically: Using validated tools like the Insomnia Severity Index and prioritizing sleep treatment can interrupt cycles that worsen mental health outcomes.

Effective psychiatric care must address sleep disturbances as primary treatment targets rather than secondary symptoms, potentially altering disease trajectories and improving long-term patient outcomes across diverse mental health conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions:

FAQs

Q1. How does insomnia relate to mental health conditions? Insomnia has a bidirectional relationship with mental health disorders. People with insomnia are 10 times more likely to develop depression and 17 times more likely to develop anxiety disorders. Conversely, about 80-90% of individuals with depression experience sleep disturbances.

Q2. Can treating insomnia improve mental health symptoms? Yes, addressing insomnia can significantly improve mental health outcomes. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) has been shown to reduce both insomnia symptoms and depression severity. In some cases, improvements in sleep can lead to substantial reductions in suicidal ideation.

Q3. What are the neurobiological links between sleep and psychiatric disorders? Several neurobiological mechanisms connect sleep and mental health, including hyperarousal of the orexin system, reduced GABAergic inhibition, and monoaminergic dysregulation. These shared pathways help explain why sleep disturbances and psychiatric symptoms often occur together and influence each other.

Q4. How does substance use affect sleep in people with mental health conditions? Substance use, particularly alcohol, can worsen sleep quality in individuals with mental health conditions. While some people use substances to self-medicate for sleep, this often leads to a cycle of dependence and further sleep disruption. Even after achieving abstinence, sleep problems may persist for extended periods.

Q5. What are the recommended treatments for comorbid insomnia in psychiatric patients? The first-line treatment for comorbid insomnia is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I), which has shown superior long-term outcomes compared to medications. For those with limited access to in-person therapy, internet-based CBT-I programs have demonstrated effectiveness. In some cases, medications like gabapentin or trazodone may be considered, especially for patients with substance use disorders.

References:

[2] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8405322/

[3] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4660250/

[4] – https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20070968

[5] – https://jcsm.aasm.org/doi/10.5664/jcsm.6460

[6] – https://www.sleepprimarycareresources.org.au/osa/assessment-questionnaires

[7] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3441938/

[8] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6657040/

[9] – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/016517818890073X#!

[10] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6289280/

[11] – https://www.nature.com/articles/s41386-019-0465-x

[12] – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1389945722012709

[13] – https://sleepdiagnostics.com.au/berlinquestionnaire

[14] – https://thoracrespract.org/articles/which-screening-questionnaire-is-best-for-predicting-obstructive-sleep-apnea-in-the-sleep-clinic-population-considering-age-gender-and-comorbidities/TurkThoracJ.2019.19024

[15] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10204467/

[16] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8394692/

[17] – https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/

fpsyt.2021.688890/full

[18] – https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/481852

[19] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3181635/

[20] – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0165032724001538

[21] – https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12888-023-05262-1

[22] – https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0218920

[23] – https://sleepapneakc.com/blog/waking-up-with-panic-attacks-sleep-apnea-connection/

[24] – https://www.additudemag.com/delayed-sleep-phase-syndrome-signs-treatments-adhd/?srsltid=AfmBOoqbUYGbL54zLWIW5328edxMCUt7QhoPv3Dx6Z2ZhtRWMHc0UFjJ

[25] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6487490/

[26] – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26598454/

[27] – https://www.ajmc.com/view/interventions-for-children-with-adhd-might-improve-sleep-outcomes

[28] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6801087/

[29] – https://www.addictioncenter.com/news/2025/10/young-adults-cannabis-alcohol-sleep/

[30] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2967491/

[31] – https://jcsm.aasm.org/doi/10.5664/jcsm.8986

[32] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3481424/

[33] – https://www.nature.com/articles/s41746-025-01847-0

[34] – https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/2791249

Video Section

Check out our extensive video library (see channel for our latest videos)

Recent Articles