Artificial Blood and Oxygen Carriers The Next Revolution in Intraoperative Safety

Abstract

The development of artificial blood and oxygen carrying substitutes represents a significant milestone in perioperative medicine, offering potential solutions to persistent challenges surrounding blood transfusion safety, supply constraints, and compatibility. Although allogeneic blood transfusion remains a cornerstone of modern surgical care, it is associated with well recognized risks, including transfusion reactions, infectious complications, immunomodulation, and logistical barriers related to storage and crossmatching. These limitations are particularly pronounced in emergency settings, rural healthcare environments, and regions with constrained blood banking infrastructure. As a result, the pursuit of safe and effective artificial blood products has become an important focus of translational research and clinical innovation.

Artificial oxygen carriers are broadly categorized into hemoglobin based oxygen carriers, perfluorocarbon emulsions, and emerging bioengineered platforms that leverage advances in nanotechnology and synthetic biology. Each class is designed to replicate the essential physiological function of erythrocytes by facilitating oxygen delivery to tissues, yet they differ substantially in composition, pharmacokinetics, and clinical utility.

Hemoglobin based oxygen carriers are among the most extensively studied alternatives. These products typically utilize purified hemoglobin derived from human, bovine, or recombinant sources that is chemically modified to enhance stability and reduce renal toxicity. Polymerization, cross linking, and encapsulation techniques have been employed to prevent rapid dissociation of hemoglobin into dimers and to prolong intravascular persistence. Early generation HBOCs generated considerable enthusiasm but were ultimately limited by safety concerns, particularly vasoconstriction, systemic hypertension, oxidative stress, and increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events. These effects were largely attributed to nitric oxide scavenging by free hemoglobin, which disrupts vascular homeostasis. More recent formulations aim to mitigate these complications through molecular stabilization and targeted delivery strategies, and several have demonstrated improved safety profiles in controlled clinical environments.

Perfluorocarbon emulsions represent a fundamentally different approach to oxygen transport. These synthetic compounds dissolve large volumes of oxygen and release it along diffusion gradients, allowing for oxygenation independent of hemoglobin binding. Their small particle size facilitates microvascular perfusion and may enhance oxygen delivery to ischemic tissues. Additionally, perfluorocarbons offer practical advantages such as long shelf life, room temperature stability in some formulations, and universal compatibility without the need for blood typing. However, their clinical adoption has been constrained by modest oxygen carrying capacity, the requirement for supplemental oxygen to maximize effectiveness, and concerns related to clearance and potential inflammatory responses.

Recent advances in nanotechnology have introduced a new generation of experimental oxygen carriers designed to more closely mimic the structure and function of natural red blood cells. These platforms include hemoglobin encapsulated within liposomes, polymer based nanoparticles, and bioengineered vesicles that seek to optimize oxygen delivery while minimizing vascular toxicity. Some investigational products are being developed with surface modifications intended to evade immune detection and prolong circulation time. Although these technologies remain largely in the investigational phase, they represent an important step toward achieving safer and more physiologically compatible substitutes.

Clinical trial data suggest that while artificial blood products are unlikely to replace donor blood in the near term, they may serve as valuable adjuncts in specific clinical scenarios. Trauma surgery has emerged as a particularly promising application, where rapid hemorrhage control often precedes the availability of crossmatched blood. Similarly, artificial oxygen carriers may benefit patients who decline transfusions for personal or religious reasons, as well as those with rare blood types or multiple alloantibodies that complicate compatibility. In austere environments such as military medicine, disaster response, and remote surgical care, the ability to store oxygen carriers for extended periods without complex refrigeration requirements could substantially improve resuscitation capabilities.

From a manufacturing perspective, artificial blood products offer several logistical advantages over conventional blood components. Many formulations can be produced at scale, standardized for quality, and stored for longer durations, thereby reducing waste associated with expiration. Universal compatibility eliminates delays related to typing and crossmatching, which is particularly valuable during time sensitive resuscitation. However, these benefits must be balanced against production costs, regulatory requirements, and the need for robust pharmacovigilance systems to monitor safety.

Immunological considerations remain central to ongoing development. Although artificial carriers are designed to minimize antigenicity, interactions with the immune system can still occur, including complement activation and inflammatory responses. Careful evaluation of these effects is necessary to ensure that short term hemodynamic benefits do not come at the expense of downstream complications.

Cost effectiveness analyses are still evolving but suggest that targeted use in high risk or resource limited settings may justify the expense, particularly if these products reduce complications associated with delayed transfusion or severe anemia. Broader economic assessments will require long term outcome data, comparative effectiveness studies, and clearer regulatory pathways.

Despite encouraging progress, several limitations continue to shape the clinical outlook for artificial blood. Vasoconstrictive effects remain a concern for certain hemoglobin based products, while relatively short intravascular half lives may necessitate repeated administration. Additionally, current formulations generally provide lower overall oxygen carrying capacity compared with native erythrocytes, restricting their role primarily to temporary support rather than complete replacement.

Future research is increasingly focused on bioengineered and hybrid solutions that integrate advances in molecular engineering, regenerative medicine, and biomaterials science. Efforts are underway to develop carriers with enhanced oxygen affinity modulation, improved rheological properties, and reduced oxidative potential. Greater emphasis is also being placed on identifying precise clinical indications where benefit is most likely, rather than pursuing universal substitution for donor blood.

In summary, artificial blood and oxygen carriers represent a rapidly evolving field with meaningful implications for perioperative and critical care practice. While early setbacks tempered initial optimism, next generation formulations demonstrate growing potential for selective clinical use. Continued innovation, rigorous clinical evaluation, and thoughtful regulatory oversight will be essential to translating these technologies into routine practice. This review integrates current evidence to support informed clinical decision making and to highlight priority areas for future investigation in the ongoing effort to develop safe, effective, and accessible alternatives to traditional blood products.

Introduction

Blood transfusion remains a foundational component of modern surgical care, playing a critical role in maintaining tissue oxygenation, restoring circulating volume, and preventing hemodynamic collapse during major procedures. Despite its life saving benefits, transfusion medicine continues to face persistent challenges that have stimulated decades of research into artificial blood substitutes. Global blood shortages remain a recurrent concern, driven by aging populations, declining donor pools, seasonal variability, and increasing procedural demands. Compatibility barriers further complicate transfusion practice, as alloimmunization and hemolytic reactions can limit the availability of suitable units for certain patients. Although screening protocols have significantly reduced the risk of infectious disease transmission, residual concerns remain, particularly in resource limited settings. Logistical constraints, including storage requirements, transport limitations, and the need for rapid availability in trauma or military environments, further reinforce the need for viable alternatives.

The concept of artificial blood has progressed substantially since early attempts that focused primarily on plasma volume expansion. Contemporary research is directed toward developing oxygen carrying solutions capable of replicating the most essential physiological functions of erythrocytes. An effective artificial blood product must support oxygen delivery to metabolically active tissues, facilitate carbon dioxide removal, preserve oncotic balance, and maintain circulatory stability without provoking adverse immunologic or inflammatory responses. Unlike donated blood, these engineered products offer several theoretical advantages, including extended shelf life, immediate readiness for use, standardized composition, and universal compatibility that eliminates the need for crossmatching. The absence of biological pathogens further enhances their appeal from a safety perspective.

Current investigative efforts generally concentrate on three principal technological pathways. The first involves hemoglobin based oxygen carriers, which utilize purified hemoglobin derived from human donors, bovine sources, or recombinant biotechnology platforms. These products are engineered to enhance molecular stability and reduce the renal toxicity historically associated with free hemoglobin. Chemical modifications such as polymerization, conjugation, and encapsulation have been explored to optimize oxygen affinity and prolong intravascular persistence. However, clinical translation has been complicated by safety concerns, including vasoconstriction related to nitric oxide scavenging, oxidative stress, and potential cardiovascular events.

The second approach centers on perfluorocarbon emulsions, synthetic compounds capable of dissolving substantial volumes of oxygen and carbon dioxide. These agents require supplemental oxygen administration to maximize their carrying capacity but offer advantages such as small molecular size, which may improve microvascular perfusion in compromised tissues. Challenges remain in achieving stable emulsification, minimizing immune activation, and ensuring efficient clearance from the body.

A third and rapidly advancing area involves nanotechnology based platforms designed to more closely mimic the structure and function of native red blood cells. Investigational strategies include hemoglobin encapsulated within biodegradable nanoparticles, liposomal constructs, and biomimetic carriers engineered to enhance circulation time while limiting toxicity. Although still largely in experimental stages, these systems reflect a growing emphasis on precision bioengineering and targeted oxygen delivery.

The surgical setting presents unique physiological and operational demands that make the development of reliable blood substitutes particularly compelling. Acute intraoperative hemorrhage can progress rapidly, leaving little time for conventional compatibility testing. In trauma care, prehospital settings, and battlefield medicine, immediate access to oxygen carrying resuscitative fluids could significantly improve survival. Artificial blood products may also provide critical solutions for patients with rare blood types, complex antibody profiles, or those who decline transfusion for personal or religious reasons. In these contexts, a universally compatible oxygen therapeutic could reduce treatment delays and expand the range of feasible surgical interventions.

Despite promising advances, several barriers must be addressed before artificial blood can achieve widespread clinical adoption. Demonstrating safety remains paramount, particularly with respect to cardiovascular stability, organ function, and long term outcomes. Establishing clear efficacy relative to conventional transfusion is equally important, as regulators require robust evidence that these products meaningfully improve patient outcomes. Manufacturing scalability, cost considerations, and supply chain integration will also influence their practicality within healthcare systems. Regulatory pathways have historically been cautious, reflecting the high stakes associated with introducing oxygen therapeutics into clinical practice.

This paper reviews the current state of artificial blood technology with an emphasis on candidates nearest to clinical implementation. It evaluates available data on safety, physiological performance, and therapeutic effectiveness, while also examining regulatory progress and the practical considerations that will shape real world adoption. Particular attention is given to the implications for surgical care, where rapid resuscitation, predictable performance, and universal compatibility could fundamentally reshape transfusion strategies.

Historical Development and Scientific Foundation

The quest for artificial blood substitutes began in the 17th century with early experiments in blood transfusion, but serious scientific development commenced in the mid-20th century. Initial attempts focused on plasma volume expanders such as dextran and gelatin solutions, which addressed circulatory volume but provided no oxygen-carrying capacity.

The first hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers emerged in the 1960s when researchers discovered that free hemoglobin could transport oxygen outside red blood cells. Early studies using stroma-free hemoglobin solutions showed promise but revealed critical safety issues, including renal toxicity and hypertension. These problems resulted from hemoglobin molecules being too small, leading to rapid renal filtration and scavenging of nitric oxide, causing vasoconstriction.

Perfluorocarbon research developed simultaneously, based on the discovery that these synthetic compounds could dissolve large quantities of oxygen and carbon dioxide. The first clinical trials of perfluorocarbon emulsions occurred in the 1980s, demonstrating oxygen transport capability but revealing limitations in oxygen-carrying capacity compared to blood.

Modern artificial blood development incorporates advanced bioengineering techniques. Hemoglobin modification strategies include cross-linking to increase molecular size, polymerization to extend circulation time, and encapsulation in liposomes or other carriers to reduce toxicity. These approaches address the fundamental challenges that limited earlier products.

The physiological requirements for effective blood substitutes are complex. Beyond oxygen transport, these products must maintain appropriate viscosity, osmotic pressure, and pH buffering capacity. They should not interfere with coagulation cascades or immune function, while providing adequate circulation time to be clinically useful.

Current understanding of oxygen transport physiology has refined design criteria for artificial blood products. The oxygen dissociation curve, which describes the relationship between oxygen partial pressure and hemoglobin saturation, guides development of products with appropriate oxygen affinity. Too high affinity prevents oxygen release to tissues, while too low affinity reduces oxygen pickup in the lungs.

Current Technologies and Products

Hemoglobin-Based Oxygen Carriers (HBOCs)

Hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers represent the most advanced category of artificial blood products currently in development. These solutions use modified hemoglobin molecules to transport oxygen while addressing the toxicity issues associated with free hemoglobin.

Polymerized Hemoglobin Solutions

Polymerized hemoglobin products link multiple hemoglobin molecules together, creating larger complexes that resist renal filtration and reduce nitric oxide scavenging. PolyHeme, developed by Northfield Laboratories, underwent extensive clinical testing but failed to gain FDA approval due to safety concerns, particularly increased cardiovascular events.

HEMOPURE (HBOC-201), derived from bovine hemoglobin, received approval in South Africa and has been used in clinical practice since 2001. This product demonstrates extended shelf life and universal compatibility but shows limited oxygen-carrying capacity compared to blood. Clinical studies indicate effectiveness in treating anemia while reducing allogeneic blood transfusion requirements.

Conjugated Hemoglobin Products

Conjugated hemoglobin solutions attach hemoglobin to polymers such as polyethylene glycol, creating products with modified pharmacokinetic properties. These modifications aim to reduce vasoconstriction while maintaining oxygen transport function. Products in this category include PEG-hemoglobin solutions currently in preclinical development.

Recombinant Hemoglobin

Advances in genetic engineering enable production of modified hemoglobin molecules with designed properties. These products can incorporate specific mutations to optimize oxygen affinity, reduce toxicity, or improve stability. While promising, recombinant hemoglobin products remain in early development stages.

Perfluorocarbon Emulsions

Perfluorocarbon-based oxygen carriers operate through a fundamentally different mechanism than hemoglobin products. These synthetic compounds dissolve oxygen directly, with carrying capacity proportional to oxygen partial pressure.

Second-Generation Perfluorocarbon Products

Early perfluorocarbon products faced challenges with long tissue retention and inadequate oxygen-carrying capacity. Second-generation products use perfluorocarbons with improved elimination profiles and enhanced emulsion stability.

Oxygent (perfluubron emulsion) underwent Phase III clinical trials but failed to demonstrate non-inferiority to blood transfusion in cardiac surgery patients. Despite this setback, the trials provided valuable safety data and identified potential applications in specific clinical scenarios.

Current perfluorocarbon research focuses on products with higher oxygen solubility and improved biocompatibility. These products may find applications as temporary oxygen bridges during surgical procedures or in situations requiring enhanced tissue oxygenation.

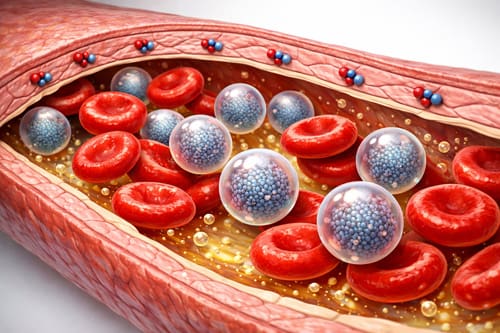

Nanotechnology-Based Solutions

Emerging nanotechnology approaches offer novel solutions to oxygen transport challenges. These products encapsulate oxygen carriers within artificial cell membranes or nanoparticles, potentially combining the advantages of different technologies.

Liposome-Encapsulated Hemoglobin

Liposome encapsulation protects hemoglobin from direct tissue contact while maintaining oxygen transport function. These products demonstrate reduced vasoconstriction compared to free hemoglobin solutions and show promise in preclinical studies.

Polymeric Nanoparticles

Synthetic nanoparticles can incorporate oxygen-carrying molecules while providing controlled release and targeting capabilities. These systems represent early-stage research but offer potential advantages in terms of customizable properties and reduced immunogenicity.

Clinical Applications and Use Cases

Trauma and Emergency Medicine

Trauma represents the most compelling application for artificial blood products due to the urgent need for volume replacement and oxygen transport in settings where blood typing and crossmatching may be impractical. Artificial blood products offer immediate availability and universal compatibility, potentially saving critical time in trauma resuscitation.

Military applications have driven much artificial blood research, as battlefield conditions present unique challenges for blood product logistics. Artificial blood products do not require refrigeration and have extended shelf life, making them ideal for forward deployment. Current military interest focuses on products that can provide temporary oxygen transport until definitive care becomes available.

Emergency medical services represent another application area where artificial blood products could provide value. Paramedic crews could carry universal oxygen carriers for immediate use in severe hemorrhage cases, potentially improving outcomes before hospital arrival.

Surgical Applications

Intraoperative blood conservation represents a growing focus in surgical practice, driven by blood shortages and increased awareness of transfusion-associated complications. Artificial blood products could serve as temporary oxygen carriers during procedures, reducing allogeneic blood exposure.

Cardiac surgery presents specific applications for artificial blood products. These procedures often require hemodilution during cardiopulmonary bypass, potentially causing anemia. Artificial oxygen carriers could maintain tissue oxygenation during hemodilution, reducing the need for blood transfusions.

Complex surgical procedures involving anticipated blood loss could benefit from prophylactic artificial blood administration. This approach could provide oxygen transport capacity while autologous blood is recovered and processed for reinfusion.

Specialized Patient Populations

Patients with multiple red blood cell antibodies present particular challenges for blood banking, as compatible units may be extremely rare. Artificial blood products could provide oxygen transport for these patients while compatible blood is located or autologous blood is prepared.

Religious populations who decline blood transfusion represent another specialized application. Artificial blood products derived from non-blood sources may be acceptable to these patients, providing treatment options for severe anemia.

Cancer patients receiving chemotherapy often develop anemia and may have compromised immune systems making infection from transfused blood particularly dangerous. Artificial blood products could provide anemia treatment without infection risk.

Critical Care Applications

Intensive care units treat patients with severe anemia who may not tolerate the hemodynamic stress of blood transfusion. Artificial blood products with gradual oxygen release could provide safer anemia treatment for critically ill patients.

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) circuits require priming with blood products, consuming valuable resources. Artificial blood products could serve as circuit priming solutions while providing oxygen transport capability.

Patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) may benefit from artificial blood products that enhance tissue oxygen delivery. These products could provide supplemental oxygen transport while lung function recovers.

Comparative Analysis with Traditional Blood Products

Safety Profile Comparison

Traditional blood transfusion carries well-established risks including infectious disease transmission, immunological reactions, and transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI). Modern blood banking practices have reduced but not eliminated these risks, maintaining the need for safer alternatives.

Artificial blood products present different safety profiles with unique risk patterns. Hemoglobin-based products show associations with hypertension and cardiovascular events, while perfluorocarbon products demonstrate generally benign safety profiles but limited efficacy.

| Parameter | Whole Blood | HBOC Products | Perfluorocarbon |

| Infection Risk | Low but present | Eliminated | Eliminated |

| Immunological Reactions | Moderate | Reduced | Minimal |

| Cardiovascular Effects | Minimal | Increased | Minimal |

| Storage Requirements | Refrigeration required | Room temperature | Refrigeration preferred |

| Shelf Life | 42 days (RBC) | 1-3 years | 2-3 years |

| Oxygen Capacity | 100% (reference) | 60-80% | 20-30% |

Efficacy Considerations

Traditional blood products provide not only oxygen transport but also hemostatic function through platelets and coagulation factors. Artificial blood products currently focus primarily on oxygen transport, requiring concurrent hemostatic support in bleeding patients.

The oxygen-carrying capacity of current artificial blood products remains below that of whole blood. While this limitation affects their utility as complete blood replacements, it may be acceptable for temporary or partial substitution applications.

Circulation time varies among products, with traditional red blood cells surviving 120 days compared to hours or days for most artificial products. This difference affects dosing frequency and overall treatment costs.

Economic Analysis

The cost structure of artificial blood products differs substantially from traditional blood products. While manufacturing costs may be higher, artificial products eliminate collection, testing, and storage infrastructure costs associated with blood banking.

Blood shortages impose economic costs through delayed surgeries and extended hospital stays. Artificial blood products could reduce these indirect costs by ensuring immediate availability of oxygen carriers.

The total cost of transfusion includes not only the blood product itself but also crossmatching, administration, and management of adverse reactions. Artificial blood products could reduce some of these associated costs through universal compatibility and reduced reaction rates.

Manufacturing and Quality Control

Production Processes

Hemoglobin-based product manufacturing begins with hemoglobin purification from red blood cells or recombinant production systems. The purification process must remove cellular debris, endotoxins, and other contaminants while preserving hemoglobin function.

Modification procedures such as polymerization or conjugation require precise control of reaction conditions to achieve consistent product properties. These processes often involve chemical cross-linking agents that must be completely removed from the final product.

Perfluorocarbon emulsion production requires specialized equipment to create stable emulsions with appropriate particle sizes. The emulsification process affects product stability and biological distribution, requiring careful optimization.

Quality Assurance Standards

Artificial blood products must meet stringent quality standards addressing oxygen transport function, sterility, pyrogenicity, and hemodynamic effects. Testing protocols include in vitro oxygen binding studies, sterility testing, and endotoxin quantification.

Stability testing evaluates product performance over extended storage periods under various conditions. These studies examine oxygen transport function, physical stability, and formation of degradation products that could affect safety.

Batch-to-batch consistency requires validated analytical methods to ensure reproducible product properties. Critical quality attributes include oxygen affinity, molecular weight distribution, and absence of contaminants.

Regulatory Requirements

Regulatory approval for artificial blood products follows standard pharmaceutical development pathways but requires specialized expertise in blood product evaluation. Regulatory agencies focus particularly on safety data given the critical nature of these products.

Phase I clinical trials evaluate safety and pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers, while Phase II studies examine efficacy in target patient populations. Phase III trials must demonstrate non-inferiority or superiority to standard blood transfusion in appropriate clinical settings.

Post-market surveillance requirements include monitoring for adverse events and periodic safety updates. Given the novelty of these products, regulatory agencies may require enhanced pharmacovigilance programs.

Challenges and Limitations

Technical Challenges

Oxygen transport optimization remains a central challenge in artificial blood development. Products must balance oxygen affinity to ensure adequate uptake in the lungs and release in tissues. Current products often show suboptimal oxygen dissociation curves compared to natural hemoglobin.

Circulation time extension requires modifications that may affect other product properties. Strategies to increase molecular size and reduce renal filtration can impact oxygen transport efficiency or introduce new toxicities.

Product stability during storage affects clinical utility and economic viability. Many artificial blood products require specialized storage conditions or have limited shelf life compared to the ideal of room temperature storage for years.

Safety Concerns

Vasoconstriction associated with hemoglobin-based products results from nitric oxide scavenging and remains incompletely resolved despite various modification strategies. This effect limits dosing and may contraindicate use in certain patient populations.

Immunogenicity of artificial products, particularly those derived from animal sources, presents ongoing concerns. While acute reactions are generally manageable, long-term immunological effects require further study.

Interference with laboratory testing can complicate patient monitoring when artificial blood products are administered. These products may affect oxygen saturation measurements, blood gas analysis, and other routine tests.

Economic Barriers

Development costs for artificial blood products are substantial, reflecting the complex manufacturing processes and extensive clinical testing requirements. These costs must be recovered through product pricing, potentially limiting adoption.

Market acceptance requires demonstration of clear clinical benefits over existing alternatives. Given the established safety profile of blood transfusion, artificial products must show either superior safety or efficacy to gain widespread adoption.

Healthcare system integration requires training of clinical staff, modification of protocols, and potentially new monitoring equipment. These implementation costs add to the total economic impact of adopting artificial blood products.

Regulatory Hurdles

The regulatory pathway for artificial blood products is complex and lengthy, reflecting the critical nature of these products and the need for extensive safety data. Previous product failures have increased regulatory scrutiny and requirements for clinical evidence.

International regulatory harmonization remains incomplete, potentially requiring separate development programs for different markets. This fragmentation increases development costs and delays global product availability.

Post-market surveillance requirements may be more stringent than for other pharmaceutical products, adding ongoing costs and administrative burden for manufacturers.

Future Directions and Emerging Technologies

Advanced Hemoglobin Engineering

Next-generation hemoglobin products incorporate sophisticated protein engineering to optimize oxygen transport while minimizing toxicity. Site-directed mutagenesis enables creation of hemoglobin variants with specific properties such as altered oxygen affinity or reduced nitric oxide binding.

Fusion proteins combining hemoglobin with other molecules offer potential advantages such as extended circulation time or additional therapeutic effects. These approaches require careful design to maintain hemoglobin function while adding desired properties.

Computational modeling of hemoglobin structure and function guides rational design of improved products. These tools enable prediction of how specific modifications will affect oxygen transport, stability, and safety.

Synthetic Biology Approaches

Synthetic biology enables creation of entirely artificial oxygen transport systems not based on natural hemoglobin. These systems could potentially overcome fundamental limitations of hemoglobin-based approaches while providing optimized oxygen transport.

Engineered microorganisms could serve as production platforms for artificial blood components, potentially reducing manufacturing costs while ensuring consistent product quality. This approach requires careful consideration of safety and regulatory requirements.

Modular design principles from synthetic biology could enable customization of artificial blood products for specific applications or patient populations. This personalized medicine approach could optimize treatment while minimizing adverse effects.

Nanotechnology Integration

Advanced nanoparticle systems offer new approaches to oxygen transport with potential advantages over molecular solutions. These systems could provide controlled release, targeting capabilities, or enhanced circulation time compared to current products.

Biomimetic approaches attempt to replicate the structure and function of red blood cells using artificial materials. These artificial cells could potentially provide not only oxygen transport but also other blood functions such as carbon dioxide removal or pH buffering.

Smart nanoparticles with responsive properties could adapt their behavior based on physiological conditions, potentially optimizing oxygen delivery based on tissue needs. These advanced systems remain in early research stages but offer exciting possibilities.

Regenerative Medicine Integration

Stem cell technology could enable production of red blood cells from patient-derived cells, potentially providing personalized blood products without the limitations of artificial alternatives. While technically challenging, this approach offers the potential for products with natural oxygen transport properties.

Tissue engineering approaches could create blood substitutes that replicate not only oxygen transport but also other blood functions. These products could potentially serve as more complete blood replacements for specific applications.

Gene therapy techniques could potentially modify patient cells to enhance oxygen transport capacity, reducing the need for artificial blood products. This approach represents a fundamentally different strategy but could address similar clinical needs.

Clinical Implementation Strategies

Healthcare System Integration

Successful implementation of artificial blood products requires careful planning for integration into existing healthcare workflows. This includes development of protocols for product selection, dosing, and monitoring that fit within current clinical practice patterns.

Training programs must address the unique properties and handling requirements of artificial blood products. Clinical staff need education on appropriate indications, contraindications, and monitoring requirements for these novel products.

Quality assurance systems must be adapted to address the specific requirements of artificial blood products. This includes storage conditions, expiration dating, and compatibility checking procedures that may differ from traditional blood products.

Clinical Decision Support

Decision support tools could help clinicians select appropriate artificial blood products based on patient characteristics and clinical situation. These tools could incorporate product-specific properties, patient factors, and clinical guidelines to optimize treatment decisions.

Monitoring protocols must account for the unique properties of artificial blood products, including their effects on laboratory testing and clinical assessment. Standardized approaches to patient monitoring could improve safety and efficacy of these products.

Outcome tracking systems could collect data on artificial blood product use to support continuous improvement in clinical practice. This data could inform future product development and clinical guidelines.

Economic Models

Cost-effectiveness analyses must consider the total cost of treatment including product costs, monitoring requirements, and clinical outcomes. These analyses should compare artificial blood products to alternatives including blood transfusion and other supportive care measures.

Payment models for artificial blood products may require development of new approaches that account for their unique value proposition. Traditional reimbursement systems may not adequately recognize the benefits of improved safety or availability.

Health technology assessment frameworks could guide decisions about adoption of artificial blood products by healthcare systems. These assessments should consider clinical effectiveness, safety, and economic impact in local healthcare contexts.

Conclusion

Key Takeaways and Clinical Implications

The development of artificial blood and oxygen carriers represents a paradigm shift in transfusion medicine with profound implications for surgical practice. Current evidence suggests that while these products may not completely replace traditional blood transfusion, they offer valuable alternatives for specific clinical situations.

Healthcare professionals should understand that artificial blood products are not equivalent to whole blood but rather represent specialized tools for oxygen transport. Their appropriate use requires consideration of specific indications, contraindications, and monitoring requirements that differ from traditional blood products.

The safety profiles of artificial blood products require careful evaluation, particularly regarding cardiovascular effects and interactions with existing medications. Clinicians must weigh these risks against the benefits of avoiding traditional blood transfusion in each clinical situation.

Economic considerations play a crucial role in the adoption of artificial blood products. While these products may have higher upfront costs than traditional blood, their benefits in terms of availability, safety, and reduced infrastructure requirements may provide overall value in appropriate applications.

Future developments in artificial blood technology are likely to improve safety and efficacy profiles, potentially expanding clinical applications. Healthcare professionals should stay informed about new products and evolving clinical evidence to optimize patient care.

The integration of artificial blood products into clinical practice requires systematic approaches to training, quality assurance, and outcome monitoring. Successful implementation depends on careful planning and ongoing evaluation of clinical experience.

Conclusion

Artificial blood and oxygen carriers stand at the threshold of clinical implementation, offering solutions to long-standing challenges in transfusion medicine. While current products face limitations in terms of oxygen-carrying capacity and safety profiles, they represent important advances toward safer, more available alternatives to traditional blood transfusion.

The surgical environment presents compelling applications for these products, particularly in trauma, emergency medicine, and specialized patient populations where traditional blood products may be unavailable or contraindicated. The universal compatibility and extended shelf life of artificial products offer particular advantages in these settings.

Ongoing research addresses current limitations through advanced engineering approaches, nanotechnology integration, and synthetic biology techniques. These developments promise future products with improved safety and efficacy profiles that could expand clinical applications.

Healthcare systems must prepare for the integration of artificial blood products through development of appropriate protocols, training programs, and quality assurance systems. The success of these products in clinical practice will depend not only on their technical properties but also on effective implementation strategies.

The economic impact of artificial blood products extends beyond direct product costs to include effects on healthcare system efficiency, blood banking infrastructure, and clinical outcomes. Cost-effectiveness analyses must consider these broader impacts to guide adoption decisions.

Regulatory pathways for artificial blood products continue to evolve, reflecting growing experience with these novel products and improved understanding of their risk-benefit profiles. Future regulatory frameworks may provide more efficient pathways for product development while maintaining appropriate safety standards.

The future of artificial blood technology holds promise for revolutionary changes in transfusion medicine. As products continue to improve and clinical experience grows, these technologies may transform surgical practice and patient care in ways that are only beginning to be realized.

Clinical adoption of artificial blood products requires evidence-based approaches that carefully evaluate their role within existing treatment paradigms. Healthcare professionals must remain engaged with ongoing research and development to effectively incorporate these technologies into patient care.

The next decade is likely to see increased availability and clinical use of artificial blood products, making familiarity with these technologies essential for healthcare professionals involved in surgical and emergency care. Preparation for this future begins with understanding current capabilities and limitations of artificial blood technologies.

Frequently Asked Questions:

What are artificial blood products and how do they work?

Artificial blood products are synthetic or modified biological solutions designed to transport oxygen and carbon dioxide in place of or alongside natural blood. They work through two main mechanisms: hemoglobin-based products use modified hemoglobin molecules to bind and release oxygen, while perfluorocarbon products dissolve gases directly in synthetic compounds.

Are artificial blood products safe for clinical use?

Current artificial blood products have specific safety profiles that differ from traditional blood. While they eliminate risks of infectious disease transmission and immunological reactions associated with blood transfusion, they present other risks such as cardiovascular effects with hemoglobin-based products. Safety depends on appropriate patient selection and clinical monitoring.

How effective are artificial blood products compared to real blood?

Current artificial blood products provide 20-80% of the oxygen-carrying capacity of natural blood, depending on the specific product. They serve as temporary oxygen carriers rather than complete blood replacements and may require higher doses or more frequent administration compared to blood transfusion.

What patients would benefit most from artificial blood products?

Patients who would benefit most include those with multiple blood antibodies making compatible blood difficult to find, individuals who decline blood transfusion for religious reasons, trauma patients requiring immediate oxygen transport, and situations where blood is unavailable such as remote locations or military settings.

How long do artificial blood products last in the body?

Circulation times vary by product type, ranging from hours to several days. This is shorter than natural red blood cells, which survive approximately 120 days. The shorter circulation time means artificial products may require repeated dosing for extended treatment.

What are the main side effects of artificial blood products?

Hemoglobin-based products can cause hypertension, cardiovascular effects, and interference with laboratory tests. Perfluorocarbon products generally have fewer side effects but may cause temporary changes in blood chemistry. All products require monitoring for allergic reactions and effects on kidney function.

How much do artificial blood products cost?

Costs vary widely depending on the product and clinical setting, but artificial blood products are generally more expensive per unit than traditional blood. However, total costs may be comparable when considering factors such as availability, storage, testing, and adverse event management.

Can artificial blood products replace blood transfusion completely?

Current artificial blood products cannot completely replace blood transfusion because they focus primarily on oxygen transport without providing other blood functions such as hemostasis, immune function, or complete nutritional support. They serve as temporary alternatives or supplements to blood transfusion.

How are artificial blood products stored and administered?

Storage requirements vary by product, with some requiring refrigeration while others can be stored at room temperature. Shelf life is generally longer than blood products, ranging from one to three years. Administration follows similar procedures to blood transfusion but may require different monitoring protocols.

What does the future hold for artificial blood technology?

Future developments focus on improving oxygen-carrying capacity, extending circulation time, reducing side effects, and potentially adding other blood functions. Advanced technologies including nanotechnology, synthetic biology, and protein engineering promise next-generation products with improved safety and efficacy profiles.

References:

Alayash, A. I. (2019). Blood substitutes: Why haven’t we been more successful? Trends in Biotechnology, 37(2), 156-166.

Belcher, D. A., Ju, J. A., Baek, J. H., Yalamanoglu, A., Buehler, P. W., & Gilkes, D. M. (2018). The quaternary state of polymerized human hemoglobin regulates oxygenation of breast cancer solid tumors: A theoretical and experimental study. PLoS One, 13(2), e0191275.

Bunn, H. F. (2013). The triumph of good over evil: Protection by the heme oxygenase system. Blood, 121(20), 4060-4062.

Chen, J. Y., Scerbo, M., & Kramer, G. (2009). A review of blood substitutes: Examining the history, clinical trial results, and ethics of hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers. Clinics, 64(8), 803-813.

D’Agnillo, F., & Chang, T. M. (1998). Polyhemoglobin-superoxide dismutase-catalase as a blood substitute with antioxidant properties. Nature Biotechnology, 16(7), 667-671.

Jahr, J. S., Mackenzie, C., Pearce, L. B., Pitman, A., & Greenburg, A. G. (2008). HBOC-201 as an alternative to blood transfusion: Efficacy and safety evaluation in a multicenter phase III trial in elective orthopedic surgery. Journal of Trauma, 64(6), 1484-1497.

Keipert, P. E. (2019). A brief history of artificial oxygen carriers and the development of perfluorocarbon emulsions. Artificial Organs, 43(1), 11-17.

Kim, H. W., & Greenberg, A. G. (2013). Artificial oxygen carriers as red blood cell substitutes: A selected review and current status. Artificial Organs, 28(9), 813-828.

Moore, E. E., Moore, F. A., Fabian, T. C., Bernard, A. C., Fulda, G. J., Hoyt, D. B., … & Weireter, L. J. (2009). Human polymerized hemoglobin for the treatment of hemorrhagic shock when blood is unavailable: The USA multicenter trial. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 208(1), 1-13.

Natanson, C., Kern, S. J., Lurie, P., Banks, S. M., & Wolfe, S. M. (2008). Cell-free hemoglobin-based blood substitutes and risk of myocardial infarction and death: A meta-analysis. JAMA, 299(19), 2304-2312.

Palmer, A. F., Sun, G., & Harris, D. R. (2009). Tangential flow filtration of hemoglobin. Biotechnology Progress, 25(1), 189-199.

Pearce, L. B., Gawryl, M. S., Rentko, V. T., Moon-Massat, P. F., & Rausch, C. W. (2006). HBOC-201 (Hemopure): Clinical studies. Blood Substitutes, 267-290.

Reiss, J. G. (2001). Oxygen carriers (“blood substitutes”) – raison d’être, chemistry, and some physiology. Chemical Reviews, 101(9), 2797-2920.

Riess, J. G. (2006). Perfluorocarbon-based oxygen delivery. Artificial Cells, Blood Substitutes, and Biotechnology, 34(6), 567-580.

Sakai, H., Sou, K., Horinouchi, H., Kobayashi, K., & Tsuchida, E. (2009). Hemoglobin-vesicles as oxygen carriers: Influence on phagocytic activity and histopathological changes in reticuloendothelial system. American Journal of Pathology, 159(3), 1079-1088.

Spahn, D. R. (2000). Current status of artificial oxygen carriers. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 40(3), 143-151.

Winslow, R. M. (2003). Current status of blood substitute research: Towards a new paradigm. Journal of Internal Medicine, 253(5), 508-517.

Zhang, J., Sun, M., & Li, P. (2020). Nanotechnology-based artificial red blood cells: From design to applications. Biomaterials Science, 8(6), 1490-1508.

Video Section

Check out our extensive video library (see channel for our latest videos)

Recent Articles