The Endocrine Disruptor Epidemic: What Should Clinicians Be Telling Patients?

Abstract

Endocrine disrupting chemicals represent a growing public health concern that requires heightened awareness and engagement from healthcare professionals across disciplines. These substances, which include both synthetic and naturally occurring compounds, have the capacity to interfere with hormonal signaling pathways that regulate growth, metabolism, reproduction, and neurodevelopment. By mimicking, blocking, or altering the synthesis, transport, and metabolism of endogenous hormones, endocrine disrupting chemicals can produce a wide range of adverse health effects in humans and wildlife. Their widespread presence in industrial products, agricultural practices, consumer goods, and the food and water supply has resulted in continuous, low level exposure across the lifespan, making complete avoidance increasingly difficult.

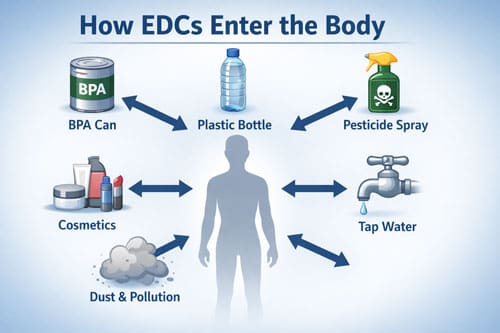

This review examines the current body of evidence linking exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals with clinically relevant health outcomes, with an emphasis on translating scientific findings into practical guidance for physicians. It synthesizes data from epidemiological studies, experimental research, and clinical observations to provide a comprehensive overview of exposure pathways, biological mechanisms, and disease associations. Common routes of exposure include ingestion of contaminated food and water, inhalation of airborne particles, and dermal absorption from personal care products and household materials. Vulnerable periods such as prenatal development, infancy, and puberty are of particular concern due to heightened sensitivity to hormonal disruption during these critical windows.

Mechanistically, endocrine disrupting chemicals exert their effects through diverse pathways, including direct interaction with hormone receptors, disruption of endocrine feedback loops, epigenetic modification, and interference with hormone synthesis and metabolism. These molecular and cellular effects have been associated with a broad spectrum of health conditions. Accumulating evidence links endocrine disrupting chemicals to reproductive disorders such as infertility, altered pubertal timing, and adverse pregnancy outcomes, as well as metabolic dysfunction including obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. Additional associations have been reported with neurodevelopmental disorders, cognitive impairment, and hormone sensitive malignancies including breast, prostate, and thyroid cancers.

Given the growing recognition of these risks, clinicians play a critical role in identifying potential exposures and guiding patients toward risk reduction. Clinical recommendations emphasize patient education on common sources of endocrine disrupting chemicals, including plastics, pesticides, food packaging, and personal care products. Practical counseling strategies may involve advising patients on safer consumer choices, dietary modifications to reduce exposure, and household practices that limit contact with environmental contaminants. For patients with conditions potentially influenced by endocrine disruption, clinicians should also consider appropriate screening and monitoring strategies as part of a comprehensive care plan.

In conclusion, endocrine disrupting chemicals present a complex and evolving challenge for modern healthcare. As scientific evidence continues to expand, clinicians must remain informed and proactive in addressing environmental determinants of health. By integrating exposure awareness, preventive counseling, and evidence based clinical management, healthcare providers can play a pivotal role in mitigating the health impacts of endocrine disrupting chemicals and supporting patients in navigating an increasingly contaminated environment.

Introduction

The human endocrine system plays a central role in regulating essential physiological processes through tightly coordinated hormonal signaling pathways. Growth, metabolism, reproduction, immune function, and neurodevelopment all depend on precise temporal and quantitative hormone action. This finely balanced system, however, is increasingly challenged by widespread environmental chemical contamination. Endocrine disrupting chemicals, commonly referred to as EDCs, have become pervasive in modern environments and are routinely encountered through daily exposure to plastics, food packaging, pesticides, industrial chemicals, personal care products, and household items.

EDCs exert their effects by mimicking endogenous hormones, antagonizing hormone receptors, altering hormone synthesis and metabolism, or disrupting signaling pathways at multiple levels. Even at low doses, particularly during critical windows of development, these compounds can induce long lasting biological effects. The resulting endocrine disruption can trigger downstream consequences across multiple organ systems, often presenting clinically as chronic, multifactorial disease. As a result, healthcare professionals frequently encounter the health consequences of EDC exposure in routine practice, often without recognizing the environmental origins of patients’ symptoms.

An expanding body of evidence now links EDC exposure to conditions historically attributed primarily to genetic susceptibility or lifestyle factors. These include infertility, polycystic ovary syndrome, endometriosis, thyroid dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, obesity, type 2 diabetes, neurodevelopmental disorders, and hormone sensitive cancers. The traditional clinical model, which emphasizes symptom management without addressing upstream environmental drivers of disease, is increasingly insufficient in this context. When chemical exposures contribute directly to disease pathogenesis, failure to identify and mitigate these factors limits the effectiveness of treatment and prevention strategies.

The implications of endocrine disruption extend beyond individual patient encounters and represent a broader population level public health challenge. Biomonitoring studies consistently demonstrate that nearly all individuals carry detectable levels of multiple EDCs in their blood, urine, and tissues. These exposures are not evenly distributed, with pregnant individuals, infants, and children facing heightened vulnerability due to rapid growth, immature detoxification systems, and increased exposure relative to body size. Transplacental transfer of EDCs allows these chemicals to reach the developing fetus, raising concerns about intergenerational health effects and the developmental origins of disease.

Against this backdrop, there is an urgent need for clinicians to develop a working understanding of EDC science and to integrate this knowledge into everyday clinical practice. The evidence base linking environmental chemical exposure to adverse health outcomes has expanded rapidly, with advances in epidemiology, toxicology, and mechanistic research providing clearer insights into causality and biological plausibility. Healthcare providers must remain informed about these developments in order to recognize exposure related conditions, counsel patients on risk reduction, and advocate for preventive strategies within both clinical and public health settings.

In an era of increasing environmental toxicity, incorporating environmental health considerations into routine medical care is no longer optional. It is a necessary evolution in clinical practice that aligns disease management with emerging scientific evidence and supports more comprehensive, preventive, and patient centered healthcare.

Understanding Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals

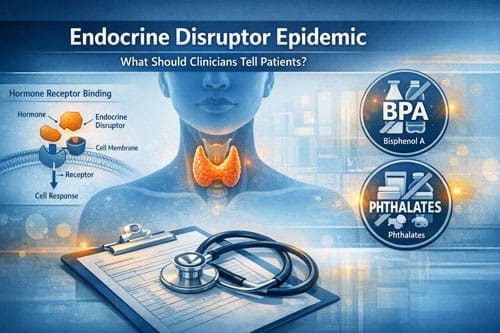

Endocrine disrupting chemicals encompass thousands of synthetic and natural substances that interfere with hormonal systems. Unlike traditional toxins that cause direct tissue damage, EDCs work at extremely low concentrations by disrupting normal hormone signaling pathways. This mechanism makes them particularly insidious, as effects may not appear for years or decades after exposure.

The endocrine system relies on precise chemical communication between organs and tissues. Hormones bind to specific receptors, triggering cellular responses that regulate growth, reproduction, metabolism, and behavior. EDCs can mimic natural hormones, leading to inappropriate cellular responses. They can also block hormone receptors, preventing normal signaling. Some EDCs alter hormone production, metabolism, or transport within the body.

These chemicals exhibit several characteristics that distinguish them from traditional toxins. Many EDCs show non-monotonic dose responses, meaning low doses can cause different or more severe effects than high doses. This challenges conventional toxicology assumptions about dose-response relationships. EDCs also demonstrate particular potency during critical developmental windows, when hormone signaling guides organ formation and functional programming.

Timing of exposure proves crucial in determining health outcomes. Fetal development, infancy, puberty, and pregnancy represent periods of heightened vulnerability. Exposures during these windows can cause permanent changes in organ structure and function, leading to disease manifestation years later. This delayed onset complicates efforts to establish cause-effect relationships in clinical settings.

The persistence and bioaccumulation of many EDCs create additional challenges. Some chemicals remain in the body for years, providing continuous low-level exposure. Others break down quickly but cause lasting changes in gene expression or organ programming. This temporal complexity requires clinicians to consider lifetime exposure patterns rather than focusing solely on current symptoms.

Major Categories and Sources of Exposure

Healthcare providers must understand the diverse sources of EDC exposure to counsel patients effectively. These chemicals permeate modern environments through industrial production, consumer products, and agricultural practices. Patients encounter EDCs through multiple pathways simultaneously, creating complex exposure patterns.

Bisphenol A (BPA) and related compounds represent one of the most studied EDC categories. These chemicals appear in polycarbonate plastics, food can linings, thermal receipt paper, and numerous consumer products. BPA exposure occurs primarily through diet, as the chemical leaches from food packaging into consumables. Even BPA-free products often contain structurally similar alternatives that may pose similar health risks.

Phthalates constitute another major EDC group, used as plasticizers and solvents in countless products. Personal care items, vinyl flooring, medical devices, and food packaging all contain various phthalates. These chemicals readily leach from products and enter the body through ingestion, inhalation, and dermal absorption. Phthalate exposure shows strong associations with reproductive and developmental disorders.

Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dioxins, and organochlorine pesticides remain in the environment decades after their production ceased. These chemicals bioaccumulate in fatty tissues and transfer through the food chain. Fish, dairy products, and meat represent primary dietary sources. Occupational and residential exposures also contribute to body burdens, particularly in contaminated communities.

Contemporary pesticides and herbicides introduce additional EDC exposures through food residues and environmental contamination. Atrazine, one of the most widely used herbicides, contaminates drinking water supplies across agricultural regions. Organophosphate pesticides appear in conventionally grown produce, while residential pest control products create indoor air contamination.

Flame retardants in furniture, electronics, and building materials represent an often-overlooked exposure source. These chemicals migrate from products into indoor air and dust, leading to inhalation and ingestion exposure. Children face particularly high exposures due to their frequent hand-to-mouth behavior and closer contact with floors and furniture.

Personal care products deliver direct EDC exposure through daily use. Parabens, triclosan, UV filters, and fragrances in cosmetics, soaps, and toiletries penetrate skin and enter systemic circulation. The frequent application and dermal absorption of these products create consistent exposure patterns, particularly among women who typically use more personal care items.

Health Effects and Clinical Manifestations

The health consequences of EDC exposure manifest across multiple organ systems and life stages. Reproductive health effects have received extensive study, revealing associations between chemical exposure and fertility problems, pregnancy complications, and developmental abnormalities. Healthcare providers treating reproductive issues must consider environmental factors alongside traditional medical causes.

Female reproductive health shows particular sensitivity to EDC exposure. Studies link various chemicals to menstrual irregularities, early puberty, polycystic ovarian syndrome, endometriosis, and pregnancy loss. BPA and phthalate exposures correlate with reduced fertility and poor assisted reproduction outcomes. Prenatal exposures affect fetal development, leading to altered birth weight, gestational age, and genital development.

Male reproductive health faces similar challenges from EDC exposure. Research demonstrates associations between chemical exposure and declining sperm quality, reduced testosterone levels, and increased rates of testicular cancer and cryptorchidism. Occupational exposures often show stronger associations, but general population studies reveal concerning trends in reproductive health parameters.

Metabolic disorders represent another major category of EDC-related health effects. Multiple chemicals show associations with obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. These “obesogens” and “diabetogens” disrupt normal metabolic programming, particularly during early development. Prenatal and early childhood exposures can predispose individuals to metabolic dysfunction throughout life.

The mechanisms linking EDC exposure to metabolic disorders involve multiple pathways. Some chemicals interfere with insulin signaling, while others affect adipocyte development and function. EDCs can alter appetite regulation, energy expenditure, and lipid metabolism. The timing of exposure influences outcomes, with early-life exposures showing particularly strong associations with later metabolic disease.

Neurodevelopmental effects of EDC exposure have gained increasing attention as autism spectrum disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder rates continue rising. Prenatal exposures to various chemicals associate with altered cognitive development, behavioral problems, and learning disabilities. The developing nervous system shows exquisite sensitivity to hormonal disruption during critical developmental windows.

Lead, mercury, and organophosphate pesticides demonstrate clear neurotoxic effects, but other EDCs also contribute to neurodevelopmental problems. Phthalates, BPA, and flame retardants show associations with altered behavior, reduced IQ, and attention problems in children. These effects often persist throughout childhood and may have lifelong implications for academic and occupational achievement.

Cancer risks associated with EDC exposure vary by chemical class and organ system. Breast cancer shows associations with multiple EDCs, including BPA, dioxins, and various pesticides. Prostate cancer rates correlate with agricultural chemical exposures. Thyroid cancer incidence has increased alongside rising EDC exposures, though multiple factors likely contribute to this trend.

The carcinogenic mechanisms of EDCs often differ from traditional carcinogens. Rather than directly damaging DNA, many EDCs promote tumor growth through hormonal pathways. Estrogen-mimicking chemicals can stimulate hormone-sensitive tumors, while other EDCs affect immune function or DNA repair mechanisms. The long latency periods between exposure and cancer diagnosis complicate epidemiological studies.

Vulnerable Populations and Critical Exposure Windows

Certain populations face disproportionate EDC exposure risks or show heightened sensitivity to these chemicals. Healthcare providers must recognize these vulnerable groups to provide appropriate screening, counseling, and intervention strategies. Pregnancy represents perhaps the most critical period, as maternal exposures affect both mother and developing fetus.

Pregnant women require specialized attention regarding EDC exposure due to physiological changes that alter chemical toxikinetics and the potential for fetal harm. Pregnancy hormones can modify EDC metabolism and clearance, while placental transfer exposes the developing fetus to maternal chemical burdens. Healthcare providers should counsel pregnant patients about exposure reduction strategies while avoiding unnecessary anxiety.

Fetal development represents the most vulnerable period for EDC exposure, as organ systems form and differentiate under precise hormonal control. Exposures during specific gestational windows can cause permanent alterations in organ structure and function. The concept of fetal programming explains how early exposures influence disease susceptibility throughout life, even in the absence of continued chemical exposure.

Infants and young children face heightened EDC exposure risks due to their behavior, physiology, and diet. Higher metabolic rates, increased food and water consumption per body weight, and developing detoxification systems create greater vulnerability to chemical effects. Children’s frequent hand-to-mouth behavior increases ingestion of contaminated dust and surfaces.

The blood-brain barrier remains immature during early development, allowing greater chemical access to the developing nervous system. This vulnerability explains the strong associations between early EDC exposure and neurodevelopmental problems. Healthcare providers caring for children should understand these exposure pathways and counsel families about risk reduction strategies.

Adolescence represents another critical exposure window as puberty involves dramatic hormonal changes. EDCs can interfere with normal pubertal development, affecting timing, progression, and outcomes. Early puberty in girls has been linked to various chemical exposures, with implications for lifelong health including increased breast cancer risk.

Occupational groups face elevated EDC exposures through workplace contact with chemicals used in manufacturing, agriculture, and other industries. Healthcare workers encounter EDCs through medical devices, cleaning products, and pharmaceutical preparations. Agricultural workers face pesticide exposures that far exceed general population levels. These occupational exposures often involve higher concentrations and different chemical mixtures than environmental exposures.

Socioeconomic factors influence EDC exposure patterns in complex ways. Lower-income communities often face higher environmental exposures due to proximity to industrial facilities, increased use of canned foods, and older housing with contaminated materials. However, higher-income groups may have greater exposures to certain chemicals through organic food preferences that reduce pesticide exposure while potentially increasing exposure to other contaminants.

Diagnostic Considerations and Clinical Assessment

Healthcare providers face challenges in recognizing EDC-related health effects due to the non-specific nature of symptoms and the long latency periods between exposure and disease manifestation. Traditional diagnostic approaches focus on immediate symptoms rather than exploring environmental contributors to chronic disease. Developing skills in environmental health assessment becomes essential for modern clinical practice.

The clinical presentation of EDC-related health effects rarely points directly to chemical exposure as the cause. Patients may present with reproductive difficulties, metabolic disorders, or neurodevelopmental concerns without mentioning potential environmental factors. Healthcare providers must adopt a systematic approach to exploring exposure histories and environmental risk factors.

Environmental health histories represent a crucial but often neglected component of clinical assessment. Effective history-taking requires understanding common exposure sources and asking targeted questions about occupational, residential, and lifestyle factors. Patients may not recognize the health relevance of their chemical exposures, making directed questioning essential.

Occupational histories should explore both current and past job exposures, including specific chemicals, protection measures, and exposure duration. Healthcare providers should inquire about agricultural work, manufacturing employment, and contact with solvents, pesticides, or other industrial chemicals. Military service history can reveal exposures to Agent Orange, burn pits, or other military-specific chemicals.

Residential exposure assessment includes housing age, renovation activities, drinking water sources, and proximity to industrial facilities. Older homes may contain lead paint or asbestos, while recent renovations can introduce new chemical exposures. Well water users face different contamination risks than those served by municipal water supplies.

Dietary assessment reveals important exposure pathways for many EDCs. Food packaging, preparation methods, and dietary patterns influence chemical intake. Regular consumption of canned foods increases BPA exposure, while frequent fish consumption may elevate mercury and PCB levels. Organic food choices reduce pesticide exposure but may not eliminate other chemical risks.

Personal care product use represents another important exposure pathway that requires clinical attention. The number and types of products used daily, along with specific ingredients, influence overall EDC exposure. Healthcare providers should ask about cosmetics, fragrances, nail products, and hair treatments, particularly when evaluating reproductive or dermatologic concerns.

Biomonitoring through blood or urine testing can document EDC exposure in certain clinical situations. However, the availability, cost, and interpretation of these tests limit their routine use. Most clinical laboratories do not offer EDC testing, and reference ranges for many chemicals remain poorly defined. The short half-lives of many EDCs mean that single measurements may not reflect long-term exposure patterns.

When biomonitoring is indicated, healthcare providers must understand the limitations and clinical utility of available tests. BPA and phthalate metabolites can be measured in urine, but levels vary dramatically based on recent exposures. Heavy metals like lead and mercury show longer detection windows and may be more clinically useful. Persistent chemicals like PCBs remain detectable years after exposure but may not reflect current exposure levels.

Patient Communication and Counseling Strategies

Effective patient communication about EDCs requires balancing scientific accuracy with practical utility while avoiding unnecessary alarm. Healthcare providers must translate complex toxicological concepts into understandable terms and actionable advice. The goal is empowering patients to make informed decisions about exposure reduction without creating paralyzing anxiety about unavoidable environmental contamination.

Risk communication represents a fundamental challenge when discussing EDCs with patients. The probabilistic nature of health risks, combined with uncertainty about individual susceptibility, complicates straightforward recommendations. Healthcare providers must help patients understand that EDC exposure increases disease risk without guaranteeing adverse outcomes in any individual case.

Framing exposure reduction as health promotion rather than disease prevention can improve patient receptivity and compliance. Emphasizing the benefits of lifestyle changes for overall health, rather than focusing solely on chemical avoidance, creates a more positive message. This approach also acknowledges that many exposure reduction strategies provide multiple health benefits beyond EDC reduction.

Patient education should focus on practical, achievable exposure reduction strategies rather than attempting to eliminate all chemical contact. Prioritizing high-impact changes that reduce exposure to the most problematic chemicals provides the greatest benefit with minimal lifestyle disruption. Healthcare providers should work with patients to identify feasible modifications that fit their specific circumstances and priorities.

Dietary recommendations represent one of the most effective areas for exposure reduction counseling. Encouraging consumption of fresh, minimally processed foods reduces exposure from food packaging chemicals. Choosing organic produce for foods with the highest pesticide residues provides targeted reduction without requiring complete dietary overhaul. Proper food storage and preparation techniques can further minimize chemical migration from packaging materials.

Home environment modifications offer additional opportunities for meaningful exposure reduction. Improving indoor air quality through ventilation, air filtration, and source control reduces inhalation exposures. Regular cleaning with simple, non-toxic products minimizes contaminated dust accumulation. Avoiding unnecessary pesticide use and choosing safer alternatives when pest control is needed protects both residents and the broader environment.

Personal care product selection provides another avenue for exposure reduction that patients can easily implement. Reading ingredient labels and avoiding products containing parabens, phthalates, and other concerning chemicals reduces dermal exposure. Choosing fragrance-free products eliminates many synthetic chemical exposures. Healthcare providers can recommend specific safer alternatives or refer patients to reliable resources for product selection guidance.

Treatment Approaches and Therapeutic Interventions

While primary prevention through exposure reduction remains the most important strategy for addressing EDC health effects, healthcare providers must also treat patients already experiencing chemical-related health problems. Treatment approaches should address both the underlying exposure and the resulting health effects through evidence-based interventions tailored to individual patient needs.

Supporting the body’s natural detoxification systems represents a foundational approach to managing EDC-related health effects. The liver, kidneys, and other organs work continuously to metabolize and eliminate chemical contaminants. Nutritional support for these systems may help optimize detoxification capacity, though healthcare providers should be cautious about unproven “detox” treatments that lack scientific evidence.

Nutritional interventions can support detoxification pathways through several mechanisms. Adequate protein intake provides amino acids needed for conjugation reactions that make chemicals more water-soluble for excretion. B vitamins serve as cofactors for many detoxification enzymes. Antioxidants like vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium help protect against oxidative stress caused by chemical metabolism.

Specific nutrients may help counteract EDC effects through various mechanisms. Calcium and vitamin D support bone health, which can be affected by lead exposure. Omega-3 fatty acids may reduce inflammation associated with chemical exposure. Folate supports DNA methylation, which can be altered by certain EDCs. However, healthcare providers should base nutritional recommendations on established science rather than speculation.

Addressing specific health conditions associated with EDC exposure requires standard evidence-based medical care combined with environmental considerations. Reproductive health problems may benefit from fertility treatments alongside exposure reduction efforts. Metabolic disorders require appropriate medical management while addressing environmental contributors to metabolic dysfunction.

Some patients may benefit from enhanced elimination procedures for specific chemicals, though these interventions require careful risk-benefit assessment. Chelation therapy can reduce heavy metal burdens in cases of documented toxicity, but it carries risks and should only be used when clearly indicated. Sauna therapy may enhance elimination of some chemicals through perspiration, but evidence for clinical benefits remains limited.

Healthcare providers should be cautious about unproven or potentially harmful treatments marketed for “chemical detoxification.” Many commercial detox programs lack scientific support and may pose health risks. Some chelation protocols have caused serious adverse effects when used inappropriately. Evidence-based medicine principles should guide all treatment decisions, even in the context of environmental health concerns.

Prevention Strategies and Risk Reduction

Prevention remains the most effective approach to addressing the EDC epidemic, requiring both individual behavior changes and broader policy interventions. Healthcare providers play crucial roles in educating patients about personal risk reduction while advocating for systemic changes that protect public health. Effective prevention strategies must address multiple exposure pathways and consider the cumulative effects of chemical mixtures.

Individual prevention strategies focus on modifiable exposure sources that patients can control through lifestyle and consumer choices. These interventions provide immediate benefits while contributing to broader market demand for safer products. Healthcare providers should help patients prioritize prevention efforts based on exposure magnitude, chemical toxicity, and individual risk factors.

Food-related prevention strategies offer substantial opportunities for exposure reduction. Choosing organic produce reduces pesticide exposure, particularly for foods with high residue levels. Minimizing consumption of canned foods and beverages reduces BPA exposure. Using glass or stainless steel containers for food storage eliminates plastic-related chemical migration. Avoiding microwaving food in plastic containers prevents heat-induced chemical release.

Water quality represents another important prevention focus. Installing appropriate water filtration systems can reduce many contaminants, though filter selection should be based on local water quality data. Avoiding plastic water bottles eliminates one source of BPA and phthalate exposure. Regular water quality testing helps identify specific contamination issues that may require targeted interventions.

Indoor air quality improvements provide multiple health benefits while reducing inhalation exposures to EDCs. Increasing ventilation rates dilutes indoor air pollutants. Using air purifiers with appropriate filtration media removes particles and some chemical vapors. Eliminating indoor pesticide use reduces direct chemical exposure while improving overall air quality.

Product selection strategies enable consumers to reduce exposure from personal care items, cleaning products, and other household goods. Reading ingredient labels and avoiding products containing known EDCs reduces direct exposure. Choosing fragrance-free products eliminates many synthetic chemical exposures. Supporting companies that prioritize chemical safety creates market incentives for safer products.

Occupational prevention requires workplace policies and practices that minimize worker exposure to EDCs. Engineering controls that reduce chemical emissions protect workers more effectively than personal protective equipment. Regular workplace air monitoring can identify contamination issues before they cause health problems. Employee education about chemical hazards and prevention strategies improves compliance with safety measures.

Policy Implications and Regulatory Considerations

The EDC epidemic reflects fundamental limitations in current chemical regulation and testing requirements. Healthcare providers must understand the regulatory landscape to effectively advocate for policies that protect patient health. Current approaches to chemical safety assessment often fail to address EDC-specific concerns, creating gaps in protection that affect clinical practice.

The United States regulates chemicals through multiple agencies and laws, creating a fragmented system with varying levels of protection. The Environmental Protection Agency oversees pesticides and industrial chemicals, while the Food and Drug Administration regulates food additives and cosmetics ingredients. This division can create regulatory gaps where harmful chemicals escape adequate oversight.

Traditional toxicity testing focuses on acute effects and cancer endpoints, often missing EDC effects that occur at low doses or after delayed periods. Standard test protocols may not capture non-monotonic dose responses or effects during critical developmental windows. This testing inadequacy means that many chemicals in commerce lack adequate safety data for EDC effects.

The concept of chemical safety has evolved to recognize that traditional approaches may be insufficient for protecting public health from EDCs. The precautionary principle suggests taking preventive action in the face of scientific uncertainty, rather than waiting for definitive proof of harm. This approach could prevent future EDC problems but requires changes in regulatory philosophy and practice.

International efforts to address EDCs provide models for potential policy approaches. The European Union has implemented stronger chemical regulations that consider EDC effects in decision-making processes. The Stockholm Convention addresses persistent organic pollutants globally, demonstrating the potential for international cooperation on chemical issues.

Healthcare providers can contribute to policy development through professional organizations, scientific research, and public advocacy. Medical societies can develop position statements on EDCs that influence policy discussions. Clinicians can participate in research that documents health effects and informs regulatory decisions. Individual healthcare providers can advocate for stronger chemical regulations through professional and personal channels.

Future Research Directions and Clinical Implications

The rapidly evolving field of EDC research continues to reveal new health effects and exposure pathways that have implications for clinical practice. Healthcare providers must stay current with emerging science while contributing to research efforts that address knowledge gaps. Future research directions will likely focus on chemical mixtures, epigenetic effects, and intervention strategies.

Mixture toxicology represents a critical research frontier, as humans are exposed to hundreds of chemicals simultaneously rather than single compounds studied in isolation. The combined effects of chemical mixtures may differ from individual chemical effects, potentially showing greater harm or unexpected interactions. Research methodologies must evolve to address mixture complexity while maintaining scientific rigor.

Epigenetic research is revealing how EDC exposure can alter gene expression without changing DNA sequences. These epigenetic changes can be inherited across generations, creating health effects in unexposed offspring. Understanding epigenetic mechanisms may explain some of the delayed and transgenerational effects observed with EDC exposure.

Personalized medicine approaches may improve the clinical management of EDC-related health effects by accounting for individual susceptibility factors. Genetic polymorphisms affect chemical metabolism and detoxification, creating variable responses to similar exposures. Biomarkers of exposure and effect could guide individualized prevention and treatment strategies.

Intervention research must evaluate the effectiveness of various exposure reduction strategies in real-world settings. While laboratory studies demonstrate chemical migration from products, practical interventions must be tested for feasibility and efficacy. Healthcare provider counseling approaches need evaluation to optimize patient behavior change and health outcomes.

Longitudinal studies following exposed populations over decades will provide crucial information about long-term health effects and critical exposure windows. These studies require substantial resources and long-term commitment but offer the best opportunity to understand EDC health effects across the lifespan. Healthcare providers can contribute by participating in research studies and helping recruit patient participants.

Biomonitoring research continues to improve our understanding of population exposure patterns and trends. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey provides ongoing surveillance of chemical exposure in the US population, revealing concerning trends and vulnerable groups. Expanding biomonitoring to include more chemicals and populations would improve exposure assessment and public health protection.

Challenges and Limitations in Clinical Practice

Healthcare providers face numerous challenges when addressing EDC-related health concerns in clinical practice. Time constraints, knowledge gaps, and limited resources create barriers to optimal patient care. Understanding these limitations helps providers work within system constraints while advocating for improvements that support better environmental health care.

Time limitations represent perhaps the greatest barrier to addressing EDCs in clinical practice. Environmental health histories require additional consultation time that may not be available in standard appointment schedules. Complex exposure assessments and counseling about prevention strategies compete with other clinical priorities for limited patient contact time.

Knowledge gaps affect both healthcare providers and patients, creating challenges in risk communication and decision-making. Medical training typically provides limited education about environmental health topics, leaving many providers ill-equipped to address EDC concerns. Patients may lack basic understanding of chemical sources and health effects, requiring extensive education before meaningful prevention discussions can occur.

Laboratory testing limitations create diagnostic challenges when healthcare providers suspect EDC-related health effects. Most clinical laboratories do not offer EDC testing, and available tests may be expensive and difficult to interpret. The absence of established reference ranges for many chemicals complicates clinical decision-making when test results are available.

Treatment options for EDC-related health effects remain limited, as most interventions focus on symptom management rather than addressing underlying exposure causes. The lack of proven treatments for many chemical-related conditions can frustrate both providers and patients seeking concrete solutions to exposure-related health problems.

Skepticism from colleagues and patients may create additional challenges for healthcare providers seeking to address environmental health concerns. Some practitioners may view EDC concerns as unproven or outside the scope of medical practice. Patients may be skeptical of environmental explanations for their health problems, preferring traditional medical approaches to diagnosis and treatment.

Insurance coverage limitations may prevent patients from accessing environmental health services or testing. Many insurance plans do not cover biomonitoring tests or environmental consultations, creating financial barriers to care. This limitation particularly affects lower-income patients who may face the highest exposure risks but have the least resources for addressing them.

Conclusion

The endocrine disruptor epidemic represents one of the most pressing environmental health challenges of our time, requiring urgent attention from healthcare providers across all specialties. The ubiquitous presence of these chemicals in modern environments, combined with their ability to disrupt essential physiological processes at extremely low doses, creates unprecedented risks for patients across all life stages.

Healthcare providers must recognize that EDC exposure contributes to many common health conditions seen in clinical practice. Reproductive disorders, metabolic dysfunction, neurodevelopmental problems, and certain cancers all show clear associations with chemical exposure. The traditional medical model of treating symptoms without addressing environmental causes proves inadequate when facing this reality.

The evidence demonstrates that certain populations face disproportionate risks from EDC exposure. Pregnant women, infants, children, and occupational groups require special attention and targeted interventions. Critical exposure windows during development create lifelong health risks that extend beyond the exposed individual to affect future generations through epigenetic mechanisms.

Clinical assessment must evolve to incorporate environmental health considerations into routine patient care. Taking adequate exposure histories, understanding common sources of EDCs, and recognizing exposure-related health patterns become essential skills for modern practitioners. While biomonitoring remains limited, clinical judgment based on exposure history and health patterns can guide appropriate interventions.

Patient communication about EDCs requires careful balance between scientific accuracy and practical utility. Healthcare providers must help patients understand risks without creating unnecessary anxiety while providing actionable guidance for exposure reduction. Focusing on achievable lifestyle modifications that provide the greatest health benefits offers the most effective approach to patient counseling.

Prevention strategies remain the most important intervention for addressing the EDC epidemic. Individual behavior changes can reduce exposure while creating market demand for safer products. However, systemic changes in chemical regulation and industrial practices are necessary to address this problem at the population level.

The regulatory system requires fundamental reforms to address EDC-specific concerns. Traditional toxicity testing approaches miss many EDC effects, while fragmented oversight creates gaps in protection. Healthcare providers must advocate for stronger chemical policies that protect public health from these pervasive contaminants.

Future research must address chemical mixtures, epigenetic effects, and intervention strategies while maintaining scientific rigor. Healthcare providers can contribute to this research while staying current with emerging evidence that affects clinical practice. The rapidly evolving nature of this field requires continuous learning and adaptation.

Despite the challenges and limitations facing healthcare providers, the growing body of evidence demands action. Patients depend on their healthcare providers for guidance about health risks and protection strategies. The failure to address EDC exposure represents a missed opportunity to prevent disease and promote health in an increasingly contaminated world.

Key Takeaways

Healthcare providers must integrate environmental health considerations into routine clinical practice to address the growing burden of EDC-related health effects. Understanding exposure sources, health effects, and prevention strategies becomes essential for modern medical practice. Patient education and counseling about exposure reduction provide practical tools for improving health outcomes while reducing disease risk.

The most effective clinical approach combines evidence-based medicine with environmental health principles. Taking adequate exposure histories, recognizing exposure-related health patterns, and providing targeted prevention guidance can improve patient outcomes across multiple health conditions. While treatment options remain limited, prevention strategies offer substantial benefits for motivated patients.

Advocacy for stronger chemical policies and safer products represents an important professional responsibility for healthcare providers. The current regulatory system fails to protect public health adequately from EDC exposure, requiring systemic changes that depend on professional and public pressure for implementation.

Continuous learning and staying current with emerging research will be necessary as the field evolves rapidly. Healthcare providers must balance scientific uncertainty with the need to provide practical guidance to patients facing real health risks from chemical exposure. The precautionary approach of recommending reasonable risk reduction strategies provides the best balance of scientific integrity and public health protection.

Frequently Asked Questions:

What are the most important EDCs that healthcare providers should know about?

The most clinically relevant EDCs include BPA and related bisphenols found in food packaging, phthalates used in personal care products and medical devices, persistent organic pollutants like PCBs and dioxins, contemporary pesticides and herbicides, flame retardants in furniture and electronics, and heavy metals like lead and mercury. These chemicals show the strongest evidence for health effects and represent major exposure sources for most patients.

How can healthcare providers identify patients who may be experiencing EDC-related health effects?

Healthcare providers should maintain high suspicion for EDC involvement in patients presenting with reproductive disorders, unexplained metabolic dysfunction, neurodevelopmental problems, or certain cancers. Taking detailed occupational, residential, and lifestyle exposure histories helps identify high-risk patients. Patterns of multiple family members with similar health problems may suggest environmental causes.

What biomonitoring tests are available for EDC exposure, and when should they be ordered?

Limited biomonitoring options include urine tests for BPA and phthalate metabolites, blood tests for persistent chemicals like PCBs, and blood or urine tests for heavy metals. These tests should be considered when exposure history suggests high exposure levels, when results would change clinical management, or when documentation is needed for workers’ compensation or legal purposes. Cost and limited availability restrict routine use.

What are the most effective exposure reduction strategies to recommend to patients?

The highest-impact recommendations include choosing organic produce for high-pesticide foods, minimizing canned food and beverage consumption, using glass or stainless steel food containers, installing appropriate water filtration, improving indoor air quality, selecting personal care products without parabens and phthalates, and avoiding unnecessary pesticide use. These strategies address major exposure sources while being achievable for most patients.

How should healthcare providers counsel pregnant patients about EDC exposure?

Pregnant patients should receive clear, practical guidance about exposure reduction without creating excessive anxiety. Focus on the most important interventions like avoiding certain fish species, choosing safer personal care products, minimizing plastic food containers, and avoiding renovation projects. Emphasize that taking reasonable precautions provides health benefits while acknowledging that complete chemical avoidance is impossible.

What role should healthcare providers play in advocating for stronger chemical regulations?

Healthcare providers can advocate through professional medical societies, participate in research documenting health effects, provide expert testimony at regulatory hearings, educate policymakers about clinical observations, and support organizations working for chemical policy reform. Professional credibility and patient care experience provide unique perspectives that can influence policy development.

How can healthcare providers stay current with rapidly evolving EDC research?

Staying current requires following key scientific journals, participating in continuing medical education focused on environmental health, joining professional organizations addressing environmental medicine, subscribing to research alerts and newsletters, and networking with colleagues working in environmental health. The Endocrine Society, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and other medical societies provide valuable resources and updates.

What should healthcare providers tell patients who are concerned about “detox” treatments for chemical exposure?

Healthcare providers should explain that the body has natural detoxification systems and that most commercial “detox” treatments lack scientific evidence. Supporting natural detoxification through adequate nutrition, hydration, and liver function is more beneficial than unproven treatments. Focus on exposure reduction as the most effective intervention while addressing any underlying health conditions with evidence-based medical care.

References:

Bergman, Å., Heindel, J. J., Jobling, S., Kidd, K. A., & Zoeller, R. T. (Eds.). (2013). State of the science of endocrine disrupting chemicals 2012. World Health Organization & United Nations Environment Programme.

Braun, J. M. (2017). Early-life exposure to EDCs: Role in childhood obesity and neurodevelopment. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 13(3), 161-173.

Di Renzo, G. C., Conry, J. A., Blake, J., DeFrancesco, M. S., DeNicola, N., Martin Jr, J. N., … & Giudice, L. C. (2015). International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics opinion on reproductive health impacts of exposure to toxic environmental chemicals. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 131(3), 219-225.

Diamanti-Kandarakis, E., Bourguignon, J. P., Giudice, L. C., Hauser, R., Prins, G. S., Soto, A. M., … & Gore, A. C. (2009). Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: An Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocrine Reviews, 30(4), 293-342.

Genuis, S. J. (2012). What’s out there making us sick? Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2012, 605137.

Gore, A. C., Chappell, V. A., Fenton, S. E., Flaws, J. A., Nadal, A., Prins, G. S., … & Zoeller, R. T. (2015). EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s second scientific statement on endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Endocrine Reviews, 36(6), E1-E150.

Hauser, R., & Calafat, A. M. (2005). Phthalates and human health. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62(11), 806-818.

Heindel, J. J., Blumberg, B., Cave, M., Machtinger, R., Mantovani, A., Mendez, M. A., … & Vom Saal, F. (2017). Metabolism disrupting chemicals and metabolic disorders. Reproductive Toxicology, 68, 3-33.

La Merrill, M. A., Vandenberg, L. N., Smith, M. T., Goodson, W., Browne, P., Patisaul, H. B., … & Rieswijk, L. (2020). Consensus on the key characteristics of endocrine-disrupting chemicals as a basis for hazard identification. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 16(1), 45-57.

Patisaul, H. B., & Adewale, H. B. (2009). Long-term effects of environmental endocrine disruptors on reproductive physiology and behavior. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 3, 10.

Rochester, J. R. (2013). Bisphenol A and human health: A review of the literature. Reproductive Toxicology, 42, 132-155.

Schug, T. T., Janesick, A., Blumberg, B., & Heindel, J. J. (2011). Endocrine disrupting chemicals and disease susceptibility. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 127(3-5), 204-215.

Street, M. E., Angelini, S., Bernasconi, S., Burgio, E., Cassio, A., Catellani, C., … & Righi, E. (2018). Current knowledge on endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) from animal biology to humans, from pregnancy to adulthood: Highlights from a national Italian meeting. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(6), 1647.

Vandenberg, L. N., Colborn, T., Hayes, T. B., Heindel, J. J., Jacobs Jr, D. R., Lee, D. H., … & Myers, J. P. (2012). Hormones and endocrine-disrupting chemicals: Low-dose effects and nonmonotonic dose responses. Endocrine Reviews, 33(3), 378-455.

Zoeller, R. T., Brown, T. R., Doan, L. L., Gore, A. C., Skakkebaek, N. E., Soto, A. M., … & Vom Saal, F. S. (2012). Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and public health protection: A statement of principles from The Endocrine Society. Endocrinology, 153(9), 4097-4110.

Video Section

Recent Articles