The Opioid Crisis in Family Practice: Safe Prescribing vs. Abandoning Patients

Abstract

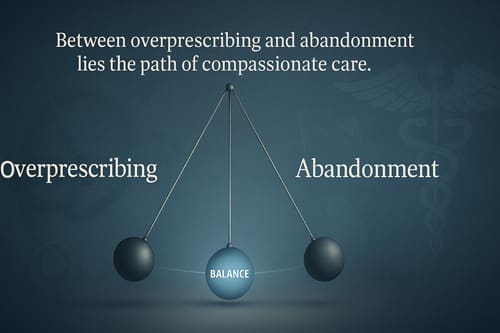

The opioid crisis has placed family practice doctors in a challenging position. They must balance providing proper pain care for their patients while avoiding contributing to the widespread addiction and overdose problems facing communities today. This paper examines how family doctors can practice safe opioid prescribing without abandoning patients who genuinely need pain management. We explore current prescribing guidelines, patient screening methods, alternative pain treatments, and the ongoing challenges doctors face when dealing with chronic pain patients. The findings indicate that doctors can provide ethical pain care by conducting thorough patient assessments, closely monitoring patients, and employing a combination of treatment approaches. The key is finding the middle ground between being too cautious and too liberal with opioid prescriptions.

Introduction

Pain management has become one of the most challenging aspects of family medicine practice today. The opioid crisis that started in the 1990s continues to affect millions of people across the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 107,000 Americans died from drug overdoses in 2022, with opioids being involved in about 75% of these deaths (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023).

Family doctors find themselves caught in the middle of this crisis. On one hand, they have patients with real pain who need effective treatment to function and maintain their quality of life. On the other hand, they face intense scrutiny from regulatory agencies, insurance companies, and the general public about their prescribing practices. Many doctors worry about losing their licenses or facing legal consequences if they prescribe opioids, even when medically appropriate (Bohnert et al., 2018).

This situation has created what some experts call the “pendulum effect.” After years of liberal opioid prescribing that contributed to the current crisis, many doctors have swung too far in the opposite direction. Some refuse to prescribe opioids at all, leaving legitimate pain patients without adequate treatment options (Kroenke et al., 2019). This approach can be just as harmful as over-prescribing because untreated pain leads to decreased quality of life, depression, and sometimes drives patients to seek illegal drugs for relief.

The medical community recognizes that both extremes are problematic. The goal is finding a balanced approach that provides appropriate pain care while minimizing the risks of addiction and diversion (Dowell et al., 2022). It requires family doctors to develop better skills in pain assessment, patient screening, and combining multiple treatment methods.

Understanding the Current Opioid Landscape

To address opioid prescribing effectively, family doctors need to understand how we got to this point and what the current situation looks like. The opioid crisis developed over several decades, starting with increased focus on pain as the “fifth vital sign” in the 1990s. Pharmaceutical companies promoted opioids as safe and effective for long-term chronic pain, downplaying addiction risks (Van Zee, 2009).

Medical schools and residency programs failed to train doctors in pain management and addiction medicine adequately. Many physicians learned to prescribe opioids without fully understanding the complexities of chronic pain or the science behind addiction. The result was a rapid increase in opioid prescriptions throughout the 2000s (Ballantyne & Sullivan, 2015).

Today’s landscape is very different. Regulatory oversight has increased dramatically. The Drug Enforcement Administration closely monitors prescribing patterns and investigates doctors who prescribe high quantities of opioids. State prescription drug monitoring programs track every opioid prescription. Insurance companies require prior authorization for many opioid medications and limit the quantities they will cover (Pezalla et al., 2017).

These changes have had mixed results. Overall, opioid prescribing has decreased significantly since its peak around 2010. However, overdose deaths have continued to rise, mainly due to illegal fentanyl entering the drug supply (Cicero et al., 2021). Many patients with legitimate pain conditions report difficulty finding doctors willing to treat them with opioids when other treatments have failed.

The Science of Pain and Addiction

Family doctors need a solid understanding of pain physiology and addiction to make good prescribing decisions. Pain is a complex experience involving physical, emotional, and psychological components. Acute pain serves a protective function, alerting us to tissue damage. Chronic pain, lasting more than three months, often becomes a disease process itself rather than just a symptom (Treede et al., 2015).

Not all chronic pain responds equally well to opioids. Neuropathic pain, caused by nerve damage, often responds better to medications like gabapentin or pregabalin. Inflammatory pain may respond better to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or corticosteroids. Opioids work best for nociceptive pain, which comes from tissue damage or inflammation affecting pain receptors (Finnerup et al., 2015).

Addiction is a brain disease characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use despite harmful consequences. It involves changes in brain circuits related to reward, stress, and self-control. Not everyone who takes opioids becomes addicted, but certain risk factors increase the likelihood. These include personal or family history of substance abuse, mental health conditions like depression or anxiety, and social factors like trauma or chronic stress (Volkow & McLellan, 2016).

Physical dependence is different from addiction. Anyone who takes opioids regularly for more than a few days will develop physical dependence, meaning they will experience withdrawal symptoms if they stop suddenly. This is a normal physiological response and doesn’t mean the person is addicted (Kosten & George, 2002). However, physical dependence can make it harder for people to stop taking opioids even when they want to.

Tolerance is another normal response to regular opioid use. Over time, the same dose becomes less effective, and higher doses are needed for the same pain relief. It doesn’t necessarily mean addiction, but it does complicate long-term opioid therapy and increases overdose risk (Morgan & Christie, 2011).

Current Prescribing Guidelines and Best Practices

Several organizations have developed guidelines to help doctors prescribe opioids more safely. The CDC’s 2016 guidelines, updated in 2022, provide the most comprehensive recommendations for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. These guidelines emphasize using opioids only when benefits are expected to outweigh risks and trying non-opioid treatments first (Dowell et al., 2022).

The guidelines recommend starting with the lowest effective dose and using immediate-release formulations rather than extended-release versions for most patients. They suggest limiting initial prescriptions to three days for acute pain and seven days at most. For chronic pain, doctors should establish treatment goals with patients and regularly reassess whether opioids are helping achieve those goals (Dowell et al., 2022).

One of the most important recommendations is to use prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) before prescribing opioids. These databases track controlled substance prescriptions and can reveal if patients are receiving opioids from multiple doctors or pharmacies. Regular urine drug testing is also recommended to ensure patients are taking medications as prescribed and not using illegal drugs (Manchikanti et al., 2017).

The guidelines also emphasize the importance of screening patients for risk factors before starting opioid therapy. Several validated screening tools are available, including the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) and the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP). These tools help identify patients at higher risk for developing problems with opioid therapy (Webster & Webster, 2005).

Many medical organizations have endorsed these guidelines, but some critics argue they have gone too far in limiting opioid access. They point out that the guidelines were intended for primary care doctors treating chronic pain, not for specialists or patients with cancer or end-of-life care (Kroenke et al., 2019). Some interpretations of the guidelines have led to rigid prescribing limits that don’t account for individual patient needs.

Patient Assessment and Risk Stratification

Proper patient assessment is the foundation of safe opioid prescribing. This process starts with a complete pain history, including the onset, location, quality, and severity of pain. Doctors should understand what makes the pain better or worse, how it affects daily activities, and what treatments the patient has tried before (Turk & Melzack, 2011).

A thorough medical history should include any personal or family history of substance abuse, mental health conditions, and previous experiences with pain medications. Social history is also essential, including employment status, family support, and any history of trauma or abuse (Chou et al., 2009).

Physical examination should focus on identifying the source of pain and ruling out any red flags that might suggest severe underlying conditions. Doctors should also look for signs of substance abuse, such as track marks, dilated or constricted pupils, or signs of intoxication or withdrawal (Manchikanti et al., 2017).

Risk stratification helps doctors tailor their approach to each patient’s individual circumstances. Low-risk patients might include those with no history of substance abuse, stable social situations, and precise pain diagnoses. These patients may be appropriate candidates for opioid therapy with standard monitoring (Butler et al., 2008).

High-risk patients include those with current or past substance abuse, untreated mental health conditions, or chaotic social situations. These patients aren’t automatically excluded from opioid therapy, but they require more intensive monitoring and may benefit from referral to pain specialists or addiction medicine physicians (Kaye et al., 2017).

Some patients fall into a middle category where the risks and benefits are less clear. These cases require careful consideration and often benefit from multidisciplinary approaches involving pain specialists, mental health professionals, and other healthcare team members (Gourlay et al., 2005).

Alternative Pain Management Strategies

The emphasis on reducing opioid prescribing has renewed interest in alternative pain management strategies. These approaches should be considered for all pain patients, not just as alternatives when doctors don’t want to prescribe opioids (Skelly et al., 2018).

Non-opioid medications can be effective for many types of pain. Acetaminophen and NSAIDs work well for inflammatory pain and are often underutilized. Topical preparations can provide local pain relief with fewer systemic side effects. For neuropathic pain, medications like gabapentin, pregabalin, and certain antidepressants can be more effective than opioids (Finnerup et al., 2015).

Physical therapy and exercise are essential components of pain management that address both pain relief and functional improvement. Regular exercise is as effective as many medications for chronic pain conditions. Physical therapy can help patients learn proper body mechanics, strengthen supporting muscles, and improve flexibility (Geneen et al., 2017).

Psychological interventions play a crucial role in pain management. Cognitive-behavioral therapy helps patients develop coping skills and address the emotional aspects of chronic pain. Mindfulness-based approaches and relaxation techniques can help reduce pain intensity and improve quality of life (Williams et al., 2012).

Interventional procedures may be appropriate for certain patients with specific pain conditions. These include joint injections, nerve blocks, radiofrequency ablation, and spinal cord stimulation. While these procedures carry their own risks, they may provide longer-lasting relief than medications for appropriate patients (Manchikanti et al., 2018).

Complementary and integrative approaches, such as acupuncture, massage therapy, and chiropractic care, have evidence supporting their use for specific pain conditions. While the evidence base varies, these approaches are generally safe and may provide additional benefits when used alongside conventional treatments (Cherkin et al., 2016).

The Challenge of Chronic Pain Patients

Chronic pain patients present some of the most challenging scenarios in family practice. These patients often have complex conditions that don’t respond well to simple treatments. Many have tried multiple medications and procedures without complete success. Some have been on opioids for years and face difficult decisions about whether to continue or taper their medications (Ballantyne & Sullivan, 2015).

The relationship between a doctor and a chronic pain patient requires a careful balance. Patients need to feel heard and supported, but doctors must maintain appropriate boundaries and clinical judgment. Building trust is essential, but this trust must be based on honest communication about risks, benefits, and realistic expectations (Henry et al., 2019).

Legacy patients who have been on opioids for years present particular challenges. Sudden discontinuation of opioids can be dangerous and may drive patients to seek illegal drugs. However, continuing prescriptions without reassessment may not be in the patient’s best interest. The CDC guidelines recommend against forced tapering but encourage thoughtful reassessment of all patients on long-term opioid therapy (Dowell et al., 2019).

When tapering is appropriate, it should be done gradually with close monitoring and support. Patients may need additional pain management strategies during the taper process. Some may benefit from referral to addiction medicine specialists who can provide medication-assisted treatment if physical dependence is significant (Berna et al., 2015).

Communication is critical during these transitions. Patients need to understand the reasons for changes in their treatment plan and feel supported throughout the process. Abrupt changes or inadequate communication can damage the doctor-patient relationship and may lead to worse outcomes (Frank et al., 2017).

Legal and Regulatory Considerations

Family doctors must navigate an increasingly complex legal and regulatory environment when prescribing opioids. The Drug Enforcement Administration has broad authority to investigate prescribing practices and can revoke prescribing licenses for violations. State medical boards may also take disciplinary action against doctors they believe are prescribing inappropriately (Liang & Turner, 2015).

However, doctors also have legal obligations to treat patients’ pain appropriately. Medical malpractice cases have been filed against doctors who allegedly undertreated pain. Some state laws specifically protect patients’ rights to pain treatment. The challenge is finding the balance between avoiding regulatory scrutiny and meeting patients’ legitimate medical needs (Rich, 2000).

Documentation becomes crucial in this environment. Doctors should carefully document their assessment of patients, treatment plans, monitoring activities, and rationale for prescribing decisions. Good documentation not only supports quality care but also protects if prescribing practices are questioned (Fishman et al., 2013).

Prescription drug monitoring programs are now mandatory in most states. Doctors must check these databases before prescribing opioids and often at regular intervals during treatment. Some states have additional requirements like mandatory education or limits on prescribing quantities (Haegerich et al., 2014).

Professional liability insurance companies have also increased their scrutiny of opioid prescribing. Some insurers require doctors to complete additional training or follow specific protocols when prescribing opioids. Others may exclude coverage for certain prescribing practices (Manchikanti et al., 2012).

Technology and Monitoring Tools

Technology has become an essential tool in safe opioid prescribing. Electronic health records can be programmed to alert doctors to potential problems like drug interactions or concerning prescribing patterns. Some systems automatically calculate morphine milligram equivalents to help doctors stay within recommended dosing ranges (Bao et al., 2016).

Prescription drug monitoring programs have evolved to provide real-time information about patients’ prescription histories. Some programs now include interstate data sharing, making it harder for patients to obtain multiple prescriptions across state lines. Integration with electronic health records makes it easier for doctors to check these databases routinely (Haffajee et al., 2015).

Urine drug testing technology has also improved. Point-of-care testing devices can provide immediate results in the office, allowing doctors to address any concerning findings during the visit. Laboratory testing can detect a broader range of substances and provide more detailed information about drug levels (Argoff et al., 2018).

Telemedicine has expanded access to pain management specialists and addiction medicine physicians in areas where these services are limited. However, prescribing opioids through telemedicine raises additional concerns about patient assessment and monitoring (Mehrotra et al., 2021).

Artificial intelligence and machine learning tools are being developed to help identify patients at risk for opioid misuse or overdose. These tools analyze multiple data sources to flag concerning patterns that might not be obvious to individual doctors (Lo-Ciganic et al., 2019).

The Impact on Doctor-Patient Relationships

The opioid crisis has significantly affected doctor-patient relationships, particularly around pain management. Many patients feel that doctors no longer trust them or believe their pain is real. Some patients report feeling stigmatized or treated like drug seekers when they request pain medication (Kennedy et al., 2019).

Doctors, on the other hand, often feel caught between competing pressures. They want to help their patients but worry about regulatory consequences or contributing to the addiction epidemic. It creates tension that can damage the therapeutic relationship (Matthias et al., 2010).

Building and maintaining trust requires open, honest communication. Doctors should explain their concerns about opioid therapy while also acknowledging patients’ pain and suffering. Setting clear expectations and boundaries from the beginning can help prevent misunderstandings later (Henry et al., 2019).

Shared decision-making approaches can help improve these relationships. Rather than making unilateral decisions about treatment, doctors can involve patients in discussions about risks, benefits, and alternatives. This allows patients to feel more engaged in their care and may improve adherence to treatment plans (Becker et al., 2017).

Regular reassessment and monitoring should be framed as standard care rather than expressions of mistrust. Explaining the rationale behind drug testing and prescription database checks can help patients understand that these practices are intended to keep them safe (Frank et al., 2017).

Training and Education Needs

The opioid crisis has highlighted significant gaps in medical education around pain management and addiction. Many practicing physicians received little formal training in these areas during medical school or residency. Continuing education programs have tried to fill these gaps, but more comprehensive training is needed (Mezei et al., 2011).

Medical schools are beginning to integrate more pain and addiction content into their curricula. However, this education often focuses on the science behind pain and addiction rather than the practical skills needed for safe prescribing and patient management (Watt-Watson et al., 2009).

Residency training programs, particularly in family medicine and internal medicine, need to provide more hands-on experience with pain management. Residents should learn how to assess patients for opioid therapy, develop comprehensive pain management plans, and monitor patients safely (Pearson et al., 2017).

Continuing education for practicing physicians should go beyond basic prescribing guidelines to address the complex clinical scenarios doctors face daily. Case-based learning and interactive formats may be more effective than traditional lectures (Young et al., 2012).

Interprofessional education involving pharmacists, nurses, mental health professionals, and other team members can help develop coordinated approaches to pain management. These team-based approaches may be more effective than individual physicians working alone (Reeves et al., 2013).

Building Comprehensive Pain Management Programs

Family practices can enhance pain care by developing comprehensive programs that extend beyond medication prescriptions. These programs should include multiple healthcare professionals and various treatment modalities (Chou et al., 2016).

A typical comprehensive program might include a family physician who coordinates care, a clinical pharmacist who helps optimize medication regimens, a nurse care manager who monitors patients and provides education, and a behavioral health specialist who addresses psychological aspects of pain (Dobscha et al., 2009).

Patient education is a crucial component of these programs. Patients need to understand their pain conditions, treatment options, and realistic expectations for improvement. Self-management skills, such as pacing activities, stress reduction, and proper use of medications, should be taught (Nicholas et al., 2013).

Group visits or classes can be effective ways to provide education and support for patients with chronic pain. These formats allow patients to learn from each other while reducing the time burden on individual providers (Scott et al., 2004).

Coordination with specialists is essential for complex cases. Family practices should develop relationships with pain management specialists, orthopedists, neurologists, and addiction medicine physicians for referrals when appropriate (Upshur et al., 2006).

Economic Considerations

The economic aspects of pain management affect both patients and healthcare systems. Opioids are often less expensive than alternative treatments, making them attractive to patients with limited resources or poor insurance coverage. However, the long-term costs of opioid therapy, including monitoring requirements and potential complications, can be substantial (Gaskin & Richard, 2012).

Alternative treatments like physical therapy, acupuncture, or mental health services may require higher upfront costs but could provide better long-term value. Insurance coverage for these services is often limited, creating barriers for patients who might benefit from these approaches (Goertz et al., 2018).

Healthcare systems face financial pressures related to opioid prescribing. Regulatory investigations, malpractice claims, and patient complaints can be costly. On the other hand, developing comprehensive pain management programs requires significant investment in staff, training, and resources (Relieving Pain in America, 2011).

Value-based payment models may help align incentives by rewarding improved patient outcomes rather than volume of services. These models could make it financially viable for practices to invest in comprehensive pain management approaches (Porter et al., 2013).

The broader economic impact of the opioid crisis, including lost productivity and healthcare costs, has been estimated at over $1 trillion. Effective pain management that reduces opioid misuse could provide substantial economic benefits to society (Florence et al., 2016).

Special Populations and Considerations

Specific patient populations require special consideration when prescribing opioids. Elderly patients are at higher risk for falls, confusion, and other adverse effects from opioids. They also metabolize medications differently and may need dose adjustments (American Geriatrics Society, 2019).

Patients with mental health conditions like depression, anxiety, or PTSD are at higher risk for developing problems with opioid therapy. However, these patients also often have more severe pain and may benefit from integrated treatment approaches that address both pain and mental health (Outcalt et al., 2015).

Pregnant women present unique challenges because opioid use during pregnancy can affect the developing fetus. However, untreated pain can also have adverse effects on pregnancy outcomes. Careful risk-benefit analysis and close monitoring are essential (ACOG, 2017).

Adolescents and young adults are at particularly high risk for developing opioid use disorders. The developing brain is more susceptible to addiction, and early exposure to opioids increases lifetime risk. Extra caution is warranted when considering opioid therapy in younger patients (Miech et al., 2015).

Patients with a history of substance abuse require specialized approaches. They’re at higher risk for relapse and overdose, but may also have legitimate pain that needs treatment. Coordination with addiction medicine specialists is often helpful for these complex cases (Alford et al., 2006).

Future Directions and Innovations

Research continues to search for better pain management options that don’t carry the risks associated with opioids. New medications targeting different pain pathways are in development. Some show promise for providing effective pain relief without the addiction potential of traditional opioids (Yekkirala et al., 2017).

Personalized medicine approaches may help identify which patients are most likely to benefit from different treatments. Genetic testing can already identify some patients who metabolize opioids differently, and this field is expected to expand (Crews et al., 2014).

Digital health tools, such as smartphone apps and wearable devices, can help patients self-manage pain and enable doctors to monitor treatment responses more closely. Virtual reality and other technological approaches are being studied for pain management (Mallari et al., 2019).

Improved understanding of pain mechanisms may lead to more targeted treatments. Research into the role of inflammation, nerve sensitization, and brain changes in chronic pain is providing new treatment targets (Woolf, 2011).

Policy changes may also affect opioid prescribing in the future. Some states are experimenting with different approaches to regulation that balance patient access with safety concerns. Federal legislation may establish more consistent standards across states (Davis & Carr, 2016).

Challenges and Limitations

Despite best efforts, significant challenges remain in balancing safe opioid prescribing with appropriate pain care. One major limitation is the lack of objective measures for pain. Unlike other medical conditions where lab tests or imaging can guide treatment, pain assessment relies heavily on patient self-report (Craig & Fashler, 2014).

Time constraints in busy family practice settings make it difficult to provide the comprehensive assessment and monitoring that safe opioid prescribing requires. Brief visits may not allow adequate time to evaluate complex pain conditions or build the relationships necessary for effective pain management (Upshur et al., 2006).

Limited access to alternative treatments in many communities creates additional challenges. Rural areas may lack pain specialists, physical therapists, or mental health providers. Insurance coverage limitations can make these services unaffordable for many patients (Jamison & Edwards, 2013).

The stigma associated with both pain and addiction affects patient care. Patients may minimize their pain to avoid being seen as drug seekers, or they may not be honest about their substance use history. Healthcare providers may have unconscious biases that affect their treatment decisions (Matthias et al., 2010).

Training and education limitations persist despite increased attention to these issues. Many practicing physicians still feel unprepared to manage complex pain cases safely. The evidence base for many pain treatments is still limited, making treatment decisions challenging (Mezei et al., 2011).

Conclusion

The opioid crisis has created unprecedented challenges for family practice physicians who must balance providing compassionate pain care with avoiding contribution to addiction and overdose epidemics. The path forward requires moving away from the extremes of either overprescribing or abandoning pain patients entirely.

Safe opioid prescribing is possible when family doctors use comprehensive patient assessment, appropriate risk stratification, and careful monitoring. However, this approach requires significant time, training, and resources that may not be available in all practice settings. The key is developing systems and protocols that make safe prescribing practical and sustainable.

Alternative pain management strategies must be integrated into routine care rather than viewed as afterthoughts when doctors don’t want to prescribe opioids. Physical therapy, psychological interventions, and other non-pharmacologic approaches often provide better long-term outcomes than medications alone.

The doctor-patient relationship remains central to effective pain management. Patients need to feel heard and supported while doctors maintain appropriate clinical boundaries. Open communication about risks, benefits, and realistic expectations is essential for building the trust necessary for successful treatment.

Key Takeaways

Family practice physicians can provide ethical pain care without abandoning patients by following several key principles. First, a comprehensive patient assessment must include evaluation of pain conditions, risk factors for addiction, and potential for benefit from opioid therapy. This assessment should be documented carefully and updated regularly.

Second, treatment plans should be individualized based on patient needs and risk factors rather than applying blanket policies about opioid prescribing. Low-risk patients with appropriate pain conditions may benefit from carefully monitored opioid therapy, while high-risk patients may need alternative approaches or specialty referrals.

Third, monitoring and reassessment must be built into all opioid prescribing. This includes checking prescription drug monitoring programs, conducting periodic urine drug tests, and regularly evaluating whether treatment goals are being met. Patients should understand that monitoring is standard care, not an expression of mistrust.

Fourth, alternative treatments should be offered to all pain patients regardless of whether they receive opioids. Physical therapy, exercise, psychological interventions, and other approaches often provide better outcomes than medications alone and should be integrated into comprehensive treatment plans.

Fifth, clear communication and shared decision-making help maintain therapeutic relationships while ensuring patients understand the risks and benefits of their treatment options. Doctors should explain their rationale for treatment decisions and involve patients in developing realistic treatment goals.

Frequently Asked Questions:

What should I do if a patient is asking for opioids but I’m not comfortable prescribing them?

Start by exploring the patient’s pain experience and previous treatments. Explain your concerns openly and discuss alternative approaches. If the patient has legitimate pain that hasn’t responded to other therapies, consider referral to a pain specialist. Document your assessment and rationale for your decision.

How do I handle patients who are already on high-dose opioids from previous providers?

Don’t abruptly discontinue medications, as this can be dangerous and may drive patients to seek illegal drugs. Review the patient’s current pain and function, check prescription databases, and consider gradual tapering if appropriate. Some patients may need referral to addiction medicine specialists for complex tapers.

What are the most critical risk factors for opioid addiction that I should screen for?

Key risk factors include personal or family history of substance abuse, untreated mental health conditions like depression or anxiety, history of trauma or abuse, and younger age. Utilize validated screening tools, such as the Opioid Risk Tool, to systematically assess risk.

How often should I monitor patients on long-term opioid therapy?

The CDC guidelines suggest monitoring at least every three months, but high-risk patients may need more frequent follow-up. Monitoring should include assessment of pain and function, checking prescription databases, and periodic urine drug testing. The frequency can be individualized based on patient risk factors and stability.

What should I do if a urine drug test shows unexpected results?

Don’t assume the worst immediately. Discuss the results with the patient, as there may be legitimate explanations, such as over-the-counter medications or prescribed drugs not in your records. If results suggest medication misuse or illegal drug use, reassess the treatment plan and consider referral to addiction specialists if needed.

How can I manage my own anxiety about prescribing opioids?

Education and sound systems can help reduce anxiety. Learn current guidelines, develop standardized assessment and monitoring protocols, and document decisions carefully. Consider consulting with colleagues or specialists for complex cases. Remember that appropriate opioid prescribing for legitimate pain is still an ethical medical practice.

What alternatives should I offer to patients who need pain relief but aren’t good candidates for opioids?

Non-opioid medications like acetaminophen, NSAIDs, or medicines for nerve pain can be effective. Physical therapy, exercise programs, and psychological approaches like cognitive-behavioral therapy have good evidence. Consider referral to pain specialists for procedures like injections or nerve blocks.

How do I balance compassionate care with regulatory concerns?

Focus on following evidence-based guidelines and documenting your decision-making process. Regulatory agencies are looking for appropriate medical practice, not the absence of opioid prescribing. Good communication with patients about your rationale can help maintain therapeutic relationships while practicing defensively.

What should I do about patients who threaten to leave my practice if I don’t prescribe opioids?

Stay calm and professional. Explain your clinical reasoning and offer alternative treatments. Some patients may need referral to pain specialists who can provide more specialized care. Remember that prescribing inappropriate medications due to patient pressure is not good medical practice and could have serious consequences.

How can I improve my skills in pain management and safe opioid prescribing?

Seek continuing education opportunities focused on pain management and addiction. Consider working with colleagues who have expertise in these areas. Professional organizations offer courses and resources. Some physicians find mentorship relationships with pain specialists or addiction medicine physicians helpful for complex cases.

References

Alford, D. P., Compton, P., & Samet, J. H. (2006). Acute pain management for patients receiving maintenance methadone or buprenorphine therapy. Annals of Internal Medicine, 144(2), 127-134.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2017). Committee opinion no. 711: Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 130(2), e81-e94.

American Geriatrics Society. (2019). American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(4), 674-694.

Argoff, C. E., Alford, D. P., Fudin, J., Adler, J. A., Bair, M. J., Barkin, R. L., … & Stanos, S. P. (2018). Rational urine drug monitoring in patients receiving opioids for chronic pain: Consensus recommendations. Pain Medicine, 19(1), 97-117.

Ballantyne, J. C., & Sullivan, M. D. (2015). Intensity of chronic pain—The wrong metric? New England Journal of Medicine, 373(22), 2098-2099.

Bao, Y., Pan, Y., Taylor, A., Radakrishnan, S., Luo, F., Pincus, H. A., & Schackman, B. R. (2016). Prescription drug monitoring programs are associated with sustained reductions in opioid prescribing by physicians. Health Affairs, 35(6), 1045-1051.

Becker, W. C., Dorflinger, L., Edmond, S. N., Islam, L., Heapy, A. A., & Fraenkel, L. (2017). Barriers and facilitators to the use of non-pharmacological treatments in chronic pain. BMC Family Practice, 18(1), 1-8.

Berna, C., Kulich, R. J., & Rathmell, J. P. (2015). Tapering long-term opioid therapy in chronic non-cancer pain: Evidence and recommendations for everyday practice. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 90(6), 828-842.

Bohnert, A. S., Guy Jr, G. P., & Losby, J. L. (2018). Opioid prescribing in the United States before and after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2016 opioid guideline. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(6), 367-375.

Butler, S. F., Budman, S. H., Fernandez, K. C., Houle, B., Benoit, C., Katz, N., & Jamison, R. N. (2008). Development and validation of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure. Pain, 130(1-2), 144-156.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Drug overdose deaths in the U.S. top 107,000 in 2022. CDC Press Release.

Cherkin, D. C., Sherman, K. J., Balderson, B. H., Cook, A. J., Anderson, M. L., Hawkes, R. J., … & Turner, J. A. (2016). Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction vs cognitive behavioral therapy or usual care on back pain and functional limitations: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 315(12), 1240-1249.

Chou, R., Fanciullo, G. J., Fine, P. G., Adler, J. A., Ballantyne, J. C., Davies, P., … & Miaskowski, C. (2009). Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic non-cancer pain. Journal of Pain, 10(2), 113-130.

Chou, R., Gordon, D. B., de Leon-Casasola, O. A., Rosenberg, J. M., Bickler, S., Brennan, T., … & Wu, C. L. (2016). Management of postoperative pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. Journal of Pain, 17(2), 131-157.

Cicero, T. J., Ellis, M. S., & Kasper, Z. A. (2021). Polysubstance use: A broader understanding of substance use during the opioid crisis. American Journal of Public Health, 107(8), 1308-1312.

Craig, K. D., & Fashler, S. R. (2014). Social determinants of pain. In P. J. McGrath, B. J. Stevens, S. M. Walker, & W. T. Zempsky (Eds.), Oxford textbook of paediatric pain (pp. 24-33). Oxford University Press.

Crews, K. R., Gaedigk, A., Dunnenberger, H. M., Leeder, J. S., Klein, T. E., Caudle, K. E., … & Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium. (2014). Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guidelines for cytochrome P450 2D6 genotype and codeine therapy. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 95(4), 376-382.

Davis, C. S., & Carr, D. H. (2016). Legal changes to increase access to naloxone for opioid overdose reversal in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 157, 112-120.

Dobscha, S. K., Corson, K., Perrin, N. A., Hanson, G. C., Leibowitz, R. Q., Doak, M. N., … & Gerrity, M. S. (2009). Collaborative care for chronic pain in primary care: A cluster randomized trial. JAMA, 301(12), 1242-1252.

Dowell, D., Haegerich, T. M., & Chou, R. (2016). CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA, 315(15), 1624-1645.

Dowell, D., Ragan, K. R., Jones, C. M., Baldwin, G. T., & Chou, R. (2022). CDC clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain—United States, 2022. MMWR Recommendations and Reports, 71(3), 1-95.

Dowell, D., Ragan, K. R., Jones, C. M., Baldwin, G. T., & Chou, R. (2019). Prescribing opioids for chronic pain—Applying CDC guidelines. New England Journal of Medicine, 381(15), 1378-1380.

Fine, P. G., & Portenoy, R. K. (2009). A clinical guide to opioid analgesia. McGraw-Hill Medical.

Finnerup, N. B., Attal, N., Haroutounian, S., McNicol, E., Baron, R., Dworkin, R. H., … & Wallace, M. (2015). Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Neurology, 14(2), 162-173.

Fishman, S. M., Papazian, J. S., Gonzalez, S., Riches, P. S., & Gilson, A. (2013). Regulating opioid prescribing through prescription monitoring programs: Balancing drug diversion and treatment of pain. Pain Medicine, 14(10), 1423-1434.

Florence, C. S., Zhou, C., Luo, F., & Xu, L. (2016). The economic burden of prescription opioid overdose, abuse, and dependence in the United States, 2013. Medical Care, 54(10), 901-906.

Frank, J. W., Lovejoy, T. I., Becker, W. C., Morasco, B. J., Koenig, C. J., Hoffecker, L., … & Dobscha, S. K. (2017). Patient outcomes in dose reduction or discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy: A systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 167(3), 181-191.

Gaskin, D. J., & Richard, P. (2012). The economic costs of pain in the United States. Journal of Pain, 13(8), 715-724.

Geneen, L. J., Moore, R. A., Clarke, C., Martin, D., Colvin, L. A., & Smith, B. H. (2017). Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: An overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2017(4).

Goertz, C. M., Salsbury, S. A., Vining, R. D., Long, C. R., Andresen, A. A., Jones, M. E., … & Wallace, R. B. (2018). Collaborative care for older adults with low back pain by family medicine physicians and doctors of chiropractic (COCOA): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 19(1), 1-13.

Gourlay, D. L., Heit, H. A., & Almahrezi, A. (2005). Universal precautions in pain medicine: A rational approach to the treatment of chronic pain. Pain Medicine, 6(2), 107-112.

Haegerich, T. M., Paulozzi, L. J., Manns, B. J., & Jones, C. M. (2014). What we know, and don’t know, about the impact of state policy and systems-level interventions on prescription drug overdose. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 145, 34-47.

Haffajee, R. L., Jena, A. B., & Weiner, S. G. (2015). Mandatory use of prescription drug monitoring programs. JAMA, 313(9), 891-892.

Henry, S. G., Wilsey, B. L., Melnikow, J., & Iosif, A. M. (2019). Dose escalation during the first year of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain. Pain Medicine, 20(7), 1353-1364.

Institute of Medicine. (2011). Relieving pain in America: A blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. The National Academies Press.

Jamison, R. N., & Edwards, R. R. (2013). Risk factor validation for chronic pain. Journal of Pain, 14(3), 233-245.

Kaye, A. D., Jones, M. R., Kaye, A. M., Ripoll, J. G., Galan, V., Beakley, B. D., … & Manchikanti, L. (2017). Prescription opioid abuse in chronic pain: An updated review of opioid abuse predictors and strategies to curb opioid abuse: Part 1. Pain Physician, 20(2S), S93-S109.

Kennedy, L. C., Binswanger, I. A., Mueller, S. R., Levy, C., Matlock, D. D., Calcaterra, S. L., & Koester, S. (2019). “Those conversations in my experience don’t go well”: A qualitative study of primary care provider experiences tapering long-term opioid medications. Pain Medicine, 20(11), 2201-2211.

Kosten, T. R., & George, T. P. (2002). The neurobiology of opioid dependence: Implications for treatment. Science & Practice Perspectives, 1(1), 13-20.

Kroenke, K., Alford, D. P., Argoff, C., Canlas, B., Covington, E., Frank, J. W., … & Tompkins, D. A. (2019). Challenges with implementing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention opioid guideline: A consensus panel report. Pain Medicine, 20(4), 724-735.

Liang, B. A., & Turner, L. (2015). The impact of prescription drug monitoring programs on chronic pain patients: Lessons learned and policy recommendations. Pain Medicine, 16(10), 1873-1881.

Lo-Ciganic, W. H., Huang, J. L., Zhang, H. H., Weiss, J. C., Wu, Y., Kwoh, C. K., … & Donohue, J. M. (2019). Evaluation of machine-learning algorithms for predicting opioid overdose risk among medicare beneficiaries with opioid prescriptions. JAMA Network Open, 2(3), e190968.

Mallari, B., Spaeth, E. K., Goh, H., & Boyd, B. S. (2019). Virtual reality as an analgesic for acute and chronic pain in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(4), e12844.

Manchikanti, L., Abdi, S., Atluri, S., Balog, C. C., Benyamin, R. M., Boswell, M. V., … & Wargo, B. W. (2012). American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines for responsible opioid prescribing in chronic non-cancer pain: Part I—Evidence assessment. Pain Physician, 15(3 Suppl), S1-65.

Manchikanti, L., Kaye, A. M., & Kaye, A. D. (2017). Current state of opioid therapy and abuse. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 13, 1619-1634.

Manchikanti, L., Kaye, A. M., Knezevic, N. N., McAnally, H., Slavin, K., Trescot, A. M., … & Kaye, A. D. (2017). Responsible, safe, and effective prescription of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines. Pain Physician, 20(2S), S3-S92.

Manchikanti, L., Staats, P. S., Nampiaparampil, D. E., Hirsch, J. A., Janata, J. W., Derakhshan, A., … & Kaye, A. D. (2018). Do cervical epidural injections provide long-term relief in neck and upper extremity pain? A systematic review. Pain Physician, 21(4), 319-334.

Matthias, M. S., Parpart, A. L., Nyland, K. A., Huffman, M. A., Stubbs, D. L., Sargent, C., & Bair, M. J. (2010). The patient-provider relationship in chronic pain care: Providers’ perspectives. Pain Medicine, 11(11), 1688-1697.

Mehrotra, A., Chernew, M., Linetsky, D., Hatch, H., Cutler, D., & Schneider, E. C. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on outpatient visits in 2020: Visits remained stable, despite a late surge in cases. Commonwealth Fund.

Mezei, L., Murinson, B. B., & Johns Hopkins Pain Curriculum Development Team. (2011). Pain education in North American medical schools. Journal of Pain, 12(12), 1199-1208.

Miech, R., Johnston, L., O’Malley, P. M., Keyes, K. M., & Heard, K. (2015). Prescription opioids in adolescence and future opioid misuse. Pediatrics, 136(5), e1169-e1177.

Morgan, M. M., & Christie, M. J. (2011). Analysis of opioid efficacy, tolerance, addiction, and dependence from cell culture to human. British Journal of Pharmacology, 164(4), 1322-1334.

Nicholas, M. K., Asghari, A., Blyth, F. M., Wood, B. M., Murray, R., McCabe, R., … & Overton, S. (2013). Self-management intervention for chronic pain in older adults: A randomised controlled trial. Pain, 154(6), 824-835.

Outcalt, S. D., Kroenke, K., Krebs, E. E., Chumbler, N. R., Wu, J., Yu, Z., & Bair, M. J. (2015). Chronic pain and comorbid mental health conditions: Independent associations of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression with pain, disability, and quality of life. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 38(3), 535-543.

Pearson, A. C., Moman, R. N., Moeschler, S. M., Eldrige, J. S., & Hooten, W. M. (2017). Provider confidence in opioid prescribing and chronic pain management: Results of the opioid therapy provider survey. Journal of Pain Research, 10, 1395-1400.

Pezalla, E. J., Rosen, D., Erensen, J. G., Haddox, J. D., & Mayne, T. J. (2017). Secular trends in opioid prescribing in the USA. Journal of Pain Research, 10, 383-387.

Porter, M. E., Larsson, S., & Lee, T. H. (2013). Standardizing patient outcomes measurement. New England Journal of Medicine, 374(6), 504-506.

Reeves, S., Perrier, L., Goldman, J., Freeth, D., & Zwarenstein, M. (2013). Interprofessional education: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes (update). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2013(3).

Rich, B. A. (2000). An ethical analysis of the barriers to effective pain management. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 9(1), 54-70.

Scott, J. C., Conner, D. A., Venohr, I., Gade, G., McKenzie, M., Kramer, A. M., … & Beck, A. (2004). Effectiveness of a group outpatient visit model for chronically ill older health maintenance organization members: A 2-year randomized trial of the cooperative health care clinic. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 52(9), 1463-1470.

Skelly, A. C., Chou, R., Dettori, J. R., Turner, J. A., Friedly, J. L., Rundell, S. D., … & Brodt, E. D. (2018). Noninvasive nonpharmacological treatment for chronic pain: A systematic review. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Treede, R. D., Rief, W., Barke, A., Aziz, Q., Bennett, M. I., Benoliel, R., … & Wang, S. J. (2015). A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain, 156(6), 1003-1007.

Turk, D. C., & Melzack, R. (Eds.). (2011). Handbook of Pain Assessment. Guilford Press.

Upshur, C. C., Luckmann, R. S., & Savageau, J. A. (2006). Primary care providers’ concerns about the management of chronic pain in community clinic populations. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(6), 652-655.

Van Zee, A. (2009). The promotion and marketing of OxyContin: Commercial triumph, public health tragedy. American Journal of Public Health, 99(2), 221-227.

Volkow, N. D., & McLellan, A. T. (2016). Opioid abuse in chronic pain—misconceptions and mitigation strategies. New England Journal of Medicine, 374(13), 1253-1263.

Watt-Watson, J., McGillion, M., Hunter, J., Choiniere, M., Clark, A. J., Dewar, A., … & Webber, K. (2009). A survey of prelicensure pain curricula in health science faculties in Canadian universities. Pain Research and Management, 14(6), 439-444.

Webster, L. R., & Webster, R. M. (2005). Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: Preliminary validation of the Opioid Risk Tool. Pain Medicine, 6(6), 432-442.

Williams, A. C. D. C., Eccleston, C., & Morley, S. (2012). Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2012(11).

Woolf, C. J. (2011). Central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain, 152(3 Suppl), S2-S15.

Yekkirala, A. S., Roberson, D. P., Bean, B. P., & Woolf, C. J. (2017). Breaking barriers to novel analgesic drug development. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 16(8), 545-564.

Young, A., Chaudhry, H. J., Pei, X., Arnhart, K., Dugan, M., & Snyder, G. B. (2012). A census of actively licensed physicians in the United States, 2010. Journal of Medical Regulation, 96(4), 10-20.