Hidden Danger: Why MIS-A Strikes Adults Months After COVID-19 Recovery

Introduction

Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Adults (MIS-A) remains a rare yet potentially serious complication of COVID-19 that predominantly affects young adults. While most COVID-19 cases resolve with mild to moderate symptoms, MIS-A typically emerges approximately four weeks after the initial infection, characterized by hyperinflammation and multiorgan involvement beyond the respiratory system. Despite its severity, MIS-A is currently underrecognized, particularly in non-Caucasian populations, suggesting a gap in clinical awareness and reporting.

What makes MIS-A particularly concerning is its delayed onset following COVID-19 recovery. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), this condition manifests during the post-recovery period, often when patients believe they have fully recuperated from their initial infection. A systematic review identified 221 patients worldwide with this syndrome, highlighting its distinctive presentation of extrapulmonary inflammation. Furthermore, unusual manifestations such as rhabdomyolysis have been documented, with patients typically responding to supportive treatment and intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. This post-COVID complication exists within a broader context where researchers estimate that 10% to 35% of COVID-19 patients develop long-term sequelae.

What is MIS-A and Why It’s Often Missed

Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Adults (MIS-A) represents a complex post-infectious complication characterized by severe multiorgan dysfunction. First recognized in 2020, this condition emerges as a delayed hyperinflammatory response following SARS-CoV-2 infection, often perplexing clinicians due to its temporal disconnect from the initial COVID-19 episode.

Definition of MIS-A in Adults

MIS-A constitutes a severe inflammatory response involving multiple organ systems that occurs in adults (≥21 years) with current or recent SARS-CoV-2 infection. This condition predominantly affects younger adults without significant comorbidities, with a median age of 21-40 years. Unlike acute COVID-19, MIS-A manifests with extrapulmonary multiorgan dysfunction, notably cardiac inflammation, gastrointestinal symptoms, and dermatological manifestations. The hyperinflammatory state is evidenced by markedly elevated inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein, ferritin, D-dimer, and interleukin-6.

The syndrome often goes unrecognized because it emerges weeks after the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection – typically 2-5 weeks post-infection – when many patients believe they have fully recovered. Additionally, some patients develop MIS-A after asymptomatic COVID-19 infections, further complicating timely diagnosis.

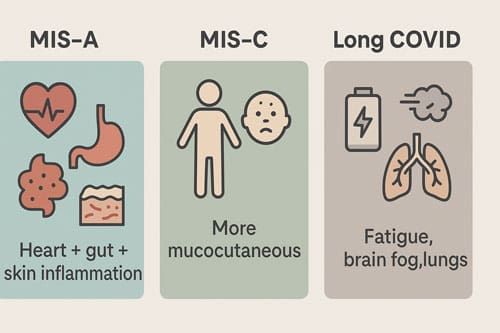

How MIS-A Differs from MIS-C and Long COVID

MIS-A shares pathophysiological similarities with Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) but presents several distinguishing features. Though both conditions involve hyperinflammation and multiorgan dysfunction, MIS-A patients generally exhibit more severe cardiac involvement and less prominent mucocutaneous symptoms compared to MIS-C cases. Moreover, MIS-A tends to have higher mortality rates than its pediatric counterpart.

In contrast to Long COVID, which involves persistent symptoms for months after infection, MIS-A presents as an acute, severe inflammatory episode with specific laboratory and clinical markers. Long COVID typically manifests as fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and respiratory issues without the dramatic inflammatory surge characteristic of MIS-A. The distinction is crucial as treatment approaches differ substantially – MIS-A requires immediate immunomodulatory intervention, whereas Long COVID management focuses on symptom control and rehabilitation.

CDC Diagnostic Criteria for MIS-A

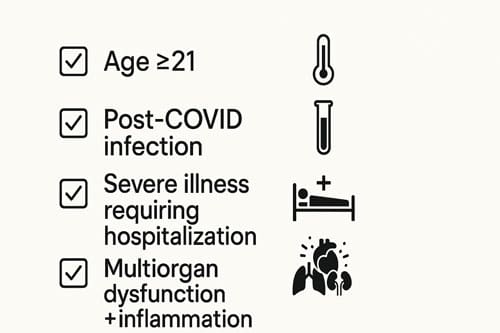

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention established specific criteria for MIS-A diagnosis to standardize identification and reporting. These criteria include:

- Age ≥21 years

- Laboratory evidence of current or recent SARS-CoV-2 infection (PCR, antigen test, or serology)

- Severe illness requiring hospitalization

- At least three of the following clinical criteria:

- Fever ≥38.0°C for ≥24 hours

- Dysfunction of at least two organ systems (cardiac, renal, respiratory, neurological, gastrointestinal, dermatological)

- Laboratory evidence of severe inflammation

- Absence of alternative plausible diagnoses

MIS-A remains underdiagnosed for several reasons. First, the temporal separation from acute COVID-19 often leads clinicians to overlook the connection. Second, the clinical presentation may mimic other inflammatory conditions such as adult-onset Still’s disease or viral myocarditis. Third, limited awareness among practitioners about this relatively new entity contributes to missed diagnoses. Lastly, variations in presentation across different demographic groups further challenge recognition, with some evidence suggesting different manifestation patterns in non-Caucasian populations.

Essentially, improving awareness of MIS-A’s diagnostic criteria among clinicians remains critical for prompt identification, appropriate management, and better understanding of this serious post-COVID complication.

Symptoms of MIS-A That Appear Weeks After COVID-19

MIS-A presents with a constellation of symptoms that typically emerge 2-6 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection, often catching patients off guard during what they perceive as their recovery phase. The syndrome’s clinical manifestations involve multiple organ systems simultaneously, creating a distinct pattern that requires prompt recognition for appropriate management.

Persistent Fever and Rash

Fever stands out as the hallmark symptom of MIS-A, observed in 100% of cases in some studies. This persistent high temperature—often exceeding 38.0°C for more than 24 hours—fails to respond to standard antipyretics. Alongside fever, approximately 57.8% of patients develop a distinctive rash. This dermatological manifestation typically appears as a non-pruritic, salmon-pink maculopapular eruption that begins on the chest and abdomen before progressively spreading to the back and extremities. In some instances, the rash manifests as discrete lesions measuring 1-2 cm, although more diffuse presentations also occur. Bloodshot eyes, indicative of non-purulent conjunctivitis, frequently accompany these symptoms and affect 40.6% of cases.

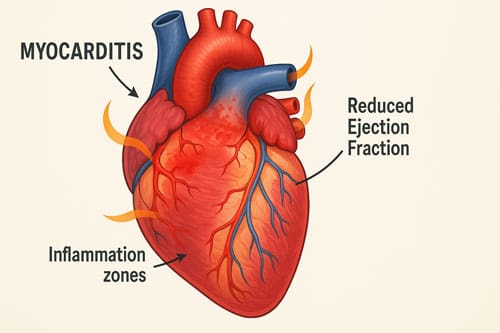

Cardiac Symptoms: Chest Pain, Myocarditis

Cardiovascular involvement represents one of the most serious aspects of MIS-A. Chest pain occurs in 12.5% of patients, often resembling symptoms of acute coronary syndrome. Echocardiographic findings reveal left ventricular dysfunction in 73.2% of cases, with ejection fractions sometimes dropping dramatically, as low as 10-15% in severe instances. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging typically shows myocardial edema and hyperemia consistent with myocarditis. Arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation, may develop as the condition progresses. Remarkably, cardiac function usually recovers within weeks following appropriate treatment.

Neurological Signs: Headache, Confusion

Neurological manifestations in MIS-A include headache in 25% of patients, often accompanied by neck stiffness mimicking meningitis. Mental status changes occur in 6.2% of cases, ranging from mild confusion to more severe alterations in consciousness. Some patients experience neuropathy, seizures, and other meningitis-like symptoms. These neurological presentations can be particularly challenging diagnostically as they may initially suggest primary neurological conditions rather than a post-COVID inflammatory syndrome.

Gastrointestinal Issues: Diarrhea, Abdominal Pain

Gastrointestinal symptoms frequently dominate the clinical picture in MIS-A. Diarrhea affects 51.6% of patients, making it the most common GI manifestation. Abdominal pain follows closely at 40.6%, often severe enough to mimic surgical emergencies. Vomiting (25%) and nausea (15.6%) complete the gastrointestinal symptom profile. In many instances, these presentations initially suggest viral gastroenteritis or inflammatory bowel disease, potentially delaying correct diagnosis.

MIS-A Symptoms in Adults Without Respiratory Illness

A distinguishing feature of MIS-A lies in its predominant extrapulmonary manifestations. Indeed, respiratory symptoms may be minimal or absent. The typical case involves “rapidly deteriorating multiorgan failure with little to no respiratory symptoms”. This characteristic differentiates MIS-A from acute COVID-19 and emphasizes why clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion even when patients lack classic COVID-19 respiratory presentations. Considering MIS-A in differential diagnosis becomes especially important for patients with multiorgan dysfunction appearing weeks after known or suspected COVID-19 infection.

Why MIS-A Strikes Weeks or Months After Recovery

The peculiar delay between COVID-19 recovery and MIS-A onset represents one of the most intriguing aspects of this syndrome. Medical researchers continue to investigate why this potentially life-threatening condition emerges weeks after patients appear to have defeated the initial viral infection.

Timeline: 2–6 Weeks Post-COVID

MIS-A typically manifests 2-6 weeks following SARS-CoV-2 infection. This consistent temporal pattern has been documented across multiple studies. Among 149 patients in one comprehensive analysis, the median time from onset of prior COVID-19 symptoms to MIS-A development was precisely 28 days (IQR, 20-36 days). Even more specifically, another study reported MIS-A diagnosis occurring at a median of 4 weeks (Q1–Q3: 2.63–5 weeks) after COVID-19.

This delayed onset pattern holds even for asymptomatic cases. Of note, 68% of patients reported a previous symptomatic COVID-19-like illness and appeared to recover fully before MIS-A emerged. The remaining individuals were presumed to have experienced asymptomatic initial infections. Consequently, some patients seek medical attention with no recognized history of COVID-19, subsequently complicating diagnosis.

The most extended documented interval between COVID-19 and MIS-A onset reached 68 days in a 67-year-old man with cirrhosis and hypertension. Hence, clinicians should maintain vigilance for up to 10 weeks post-infection in certain high-risk groups.

Delayed Immune Response and Cytokine Storm

The pathophysiology underlying MIS-A involves a complex dysregulated immune response. Unlike acute COVID-19, MIS-A results from a delayed and irregular immune reaction that activates after apparent recovery. In normal SARS-CoV-2 infection, inflammatory responses activate both innate and acquired immune systems. Subsequently, as recovery progresses, this inflammation typically resolves.

Conversely, in MIS-A patients, an aberrant immune response develops during the recovery period. This process likely involves macrophage activation leading to hyperinflammation. Laboratory investigations reveal profound immune dysregulation, with 98% of tested patients showing elevated interleukin-6 levels. Likewise, 91% exhibited increased ferritin and fibrinogen levels.

The resulting cascade includes reactivation of both innate and acquired immune components, involving B cells, T cells, and excessive proinflammatory cytokine production. It creates what clinicians term a “cytokine storm,” causing widespread inflammation across multiple organ systems. The hypercoagulation state frequently observed stems from this prolonged cytokine response.

Role of Antibody-Mediated Inflammation

Mounting evidence suggests antibody-mediated processes play a central role in MIS-A pathogenesis. Remarkably, 30% of adults in a CDC report demonstrated negative PCR results yet tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. This pattern strongly supports MIS-A as a postinfectious phenomenon rather than direct viral damage.

Several mechanisms may explain this antibody-mediated pathology. First, antibodies potentially augment inflammatory responses by triggering host immune activity. Second, evidence suggests antibody-dependent enhancement of viral entry, resembling processes observed in dengue fever. Third, the S-protein may function as a superantigen, directly triggering MIS-A symptoms.

A particularly telling observation involves complement system abnormalities. Case reports document reduced complement fractions, especially in patients with severe thrombocytopenia, indicating activation via the classical pathway linked to immune complex formation. This finding aligns with the hypothesis that MIS-A represents an antibody-mediated immune response.

Some researchers propose that persistent viral antigens outside the respiratory tract might continuously stimulate antibody production. Others emphasize endothelial damage and microthrombosis affecting multiple organs as key pathophysiological processes. These mechanisms explain why MIS-A primarily manifests as a multisystem inflammatory condition rather than a respiratory principal illness.

How MIS-A is Diagnosed in Clinical Settings

Diagnosing Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Adults requires a methodical clinical approach, as its presentation often mimics several other conditions. Clinicians must employ a combination of laboratory tests, imaging studies, and exclusion criteria to identify this post-COVID complication accurately.

Key Lab Markers: CRP, Ferritin, D-dimer

Laboratory evidence of inflammation stands as the cornerstone of MIS-A diagnosis. C-reactive protein (CRP) typically shows marked elevation, with median values of 28.2 mg/L (IQR: 14.65) reported in 93% of cases. Similarly, ferritin levels rise substantially, with median values of 1014 ng/mL (IQR: 1619.55) documented in 85.9% of patients. D-dimer elevation, present in 91% of cases, reflects the hypercoagulable state accompanying this syndrome.

Additional inflammatory markers include procalcitonin (PCT), with median values of 8.32 μg/L (IQR: 13.26), and interleukin-6, with median values of 86 pg/mL (IQR: 296). Notably, lymphopenia occurs in 86% of patients, often alongside neutrophilia, creating a characteristic pattern that aids in diagnosis.

Cardiac Imaging and EKG Findings

Cardiac evaluation becomes essential for any suspected MIS-A case. Echocardiography frequently reveals left ventricular systolic dysfunction, regional wall motion abnormalities, or pericardial effusion. Electrocardiographic changes, typically nonspecific, may include ST-segment abnormalities, T-wave inversions, PR segment depression, or low-voltage QRS.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) provides valuable diagnostic information through tissue characterization. CMR findings often demonstrate diffuse myocardial edema, focal subepicardial or intramural cardiac edema, with or without evidence of fibrosis on late gadolinium enhancement sequences. These findings help confirm myocarditis in the MIS-A clinical picture.

RT-PCR vs Serology in MIS-A Diagnosis

Since MIS-A typically develops weeks after acute infection, RT-PCR testing alone proves insufficient. In fact, only 32% of patients tested positive on both PCR and serological tests. Nonetheless, 98% showed evidence of current or past COVID-19 infection when both testing modalities were employed.

Among 149 patients in one analysis, 72% demonstrated positive SARS-CoV-2 serology. Therefore, clinicians should utilize both nucleic acid testing and antibody detection when evaluating suspected cases, particularly when patients present 2-5 weeks post-COVID infection.

Exclusion of Other Causes

Differential diagnosis represents a critical component, as MIS-A mimics several conditions. Common alternatives to exclude include septic shock, acute rheumatic fever, systemic lupus erythematosus, adult-onset Still’s disease, and acute viral myocarditis. Additional considerations involve Kawasaki disease, rickettsial disease, and acute viral infections.

Exclusion criteria must rule out severe respiratory illness to distinguish MIS-A from acute COVID-19 pneumonia. Through comprehensive evaluation and application of CDC criteria, clinicians can accurately diagnose this potentially life-threatening post-COVID syndrome.

Treatment Options and Recovery Outlook for MIS-A

Management of MIS-A requires prompt intervention with both immunomodulatory therapy and supportive measures to prevent potentially fatal outcomes. Early recognition remains vital for treatment success.

MIS-A Treatment: IVIG and Corticosteroids

Immunomodulatory therapy forms the cornerstone of MIS-A treatment. Corticosteroids, primarily methylprednisolone, prednisone, and dexamethasone, are employed in most cases. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) serves as another first-line option, typically administered at 2 g/kg based on ideal body mass. Occasionally, physicians utilize additional biological agents such as anakinra (anti-IL-1α) in approximately 11% of cases, tocilizumab (anti-IL-6 receptor) in 7% of patients, and rarely, eculizumab or plasmapheresis.

Supportive Care: Oxygen, Fluids, ICU Monitoring

Beyond immunomodulation, supportive measures include heart failure therapy (beta-blockers, diuretics, ACE inhibitors), anticoagulation, and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Approximately 55% of patients require intensive care unit admission. Thrombotic prophylaxis becomes essential given the hypercoagulable state typically associated with MIS-A.

Recovery Time and Long-Term Effects

The median hospitalization duration reaches 10 days (IQR: 7–14 days). Remarkably, even with severe presentations, mortality remains relatively low at 5.6%. Acute kidney injury emerges as the most frequent complication. For survivors, inflammatory markers and cardiac abnormalities typically normalize within 4-6 weeks.

Can MIS-A Recur After Treatment?

Currently, limited data exist regarding MIS-A recurrence following successful treatment. However, ongoing follow-up, particularly cardiac monitoring, is recommended for patients who have experienced cardiac manifestations. Exercise restrictions may apply until cardiologists confirm complete recovery.

Conclusion

Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Adults represents a rare yet potentially life-threatening consequence of SARS-CoV-2 infection that demands heightened clinical awareness. This syndrome characteristically emerges 2-6 weeks after apparent recovery from COVID-19, often catching both patients and clinicians off guard due to its temporal disconnect from the initial infection. Unlike acute COVID-19, MIS-A manifests primarily as extrapulmonary inflammation affecting multiple organ systems, particularly the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, dermatological, and neurological systems.

The pathophysiological mechanisms behind MIS-A involve a dysregulated immune response, leading to a cytokine storm and widespread inflammation. Evidence points toward antibody-mediated processes playing a central role, explaining why this condition emerges during the post-infectious period rather than during active viral replication. This delayed hyperinflammatory response distinguishes MIS-A from both acute COVID-19 and Long COVID syndromes.

Prompt diagnosis remains crucial for effective management. Clinicians should maintain high vigilance for patients presenting with persistent fever, multiorgan dysfunction, and elevated inflammatory markers (CRP, ferritin, D-dimer) within weeks of COVID-19 infection. Additionally, cardiac evaluation through echocardiography and EKG becomes essential due to the frequency of myocarditis and other cardiac manifestations. Both serological and RT-PCR testing may prove necessary since many patients no longer harbor active viral particles when MIS-A symptoms emerge.

Treatment protocols primarily involve immunomodulatory therapies, especially corticosteroids and intravenous immunoglobulin. Biological agents targeting specific cytokines serve as second-line options in refractory cases. Supportive care, including intensive monitoring, often proves necessary during the acute phase. Therefore, a multidisciplinary approach involving infectious disease specialists, cardiologists, and critical care physicians offers the most comprehensive management strategy.

The recovery outlook appears relatively favorable despite the syndrome’s severity. Most patients respond well to appropriate treatment, with mortality rates remaining under 6%. Though long-term follow-up data remain limited, available evidence suggests normalization of inflammatory markers and cardiac function within weeks to months of treatment.

Future research directions should focus on identifying risk factors for developing MIS-A after COVID-19, refining diagnostic criteria to improve early detection, and establishing standardized treatment protocols based on clinical severity. Until then, healthcare providers must remain alert to this potential complication, especially in young adults who present with multisystem inflammation weeks after COVID-19 recovery. Indeed, increased awareness, early recognition, and prompt intervention represent the best strategy for managing this challenging post-COVID syndrome.

Frequently Asked Questions:

FAQs

Q1. What is Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Adults (MIS-A)? MIS-A is a rare but serious post-COVID-19 complication characterized by severe inflammation affecting multiple organ systems. It typically occurs 2-6 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection, even in those who had mild or asymptomatic cases.

Q2. What are the main symptoms of MIS-A? Key symptoms include persistent high fever, rash, cardiac issues like chest pain and myocarditis, neurological signs such as headache and confusion, and gastrointestinal problems like diarrhea and abdominal pain. Notably, respiratory symptoms may be minimal or absent.

Q3. How is MIS-A diagnosed? Diagnosis involves a combination of clinical presentation, laboratory tests showing elevated inflammatory markers (CRP, ferritin, D-dimer), cardiac imaging, and evidence of recent SARS-CoV-2 infection through PCR or antibody testing. Other potential causes must be excluded.

Q4. What treatment options are available for MIS-A? Treatment primarily consists of immunomodulatory therapy, including corticosteroids and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Supportive care, such as oxygen therapy and fluid management, is also crucial. Some patients may require intensive care unit monitoring.

Q5. What is the recovery outlook for patients with MIS-A? Despite its severity, the prognosis for MIS-A is generally favorable with prompt treatment. Most patients recover within weeks, with inflammatory markers and cardiac function typically normalizing within 4-6 weeks. However, long-term follow-up is recommended, especially for those who experienced cardiac complications.

References:

[1] – https://www.cdc.gov/mis/about/index.html

[2] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9754714/

[3] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8488713/

[4] – https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/75/11/1903/6571412

[5] – https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/JAHA.123.032143

[6] – https://www.healthline.com/health/multi-system-inflammatory-syndrome

[8] – https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/1165849

[9] – https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2784427

[10] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11392540/

[11] – https://journals.lww.com/joim/fulltext/2023/11010/multisystem_

inflammatory_syndrome_in_adults___in.2.aspx

[12] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11594674/

[13] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9403161/

[14] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8830159/

[15] – https://www.cdc.gov/mis/hcp/clinical-care-treatment/index.html

[16] – https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-022-07303-8

[17] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10809493/