Giant Cell Arteritis and the Rapid Rise of Tocilizumab: Are Steroids Obsolete?

Abstract

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is the most common form of primary systemic vasculitis in adults over 50 years of age and represents a major cause of morbidity, particularly when diagnosis and treatment are delayed. Traditionally, management has relied on prolonged courses of high-dose corticosteroids, which remain effective in inducing remission but are associated with a rising burden of adverse effects, including osteoporosis, diabetes, hypertension, infection, and cardiovascular complications. The need to balance efficacy with safety has driven the search for steroid-sparing therapies.

The introduction of tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 receptor antagonist, has markedly changed the therapeutic landscape of GCA. Evidence from randomized controlled trials, particularly the pivotal GiACTA study, and subsequent real-world clinical experience has demonstrated that tocilizumab, administered weekly or every other week in combination with a 26-week prednisone taper, is superior to both 26-week and 52-week prednisone tapering regimens plus placebo in achieving sustained glucocorticoid-free remission. Beyond efficacy, tocilizumab has shown the potential to reduce cumulative glucocorticoid exposure, thereby lowering the risk of long-term steroid-related toxicity and improving patient quality of life.

Despite these advances, the question of whether corticosteroids have become obsolete in GCA management remains complex. Corticosteroids remain indispensable in the acute setting, particularly in preventing vision loss, managing cranial ischemic complications, and stabilizing patients before the initiation of biologic therapy. In addition, barriers such as cost, accessibility, and contraindications to biologic therapy continue to influence clinical decision-making. Safety considerations, including the risk of infection with biologic therapy and long-term data that remain limited compared with corticosteroids, also warrant careful evaluation.

This review integrates evidence from clinical trials, real-world practice, and economic analyses to assess the evolving role of corticosteroids and tocilizumab in GCA treatment. Our findings suggest that while tocilizumab has transformed long-term disease control and remarkably reduced glucocorticoid dependence, corticosteroids continue to serve as a cornerstone in acute management and as a bridging therapy in various clinical scenarios. The future of GCA treatment is likely to be defined by individualized, combination-based approaches that maximize therapeutic efficacy while minimizing long-term morbidity.

Keywords: giant cell arteritis, tocilizumab, corticosteroids, interleukin-6, vasculitis, steroid-sparing therapy

Introduction

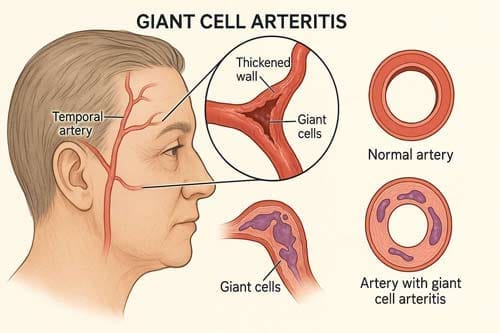

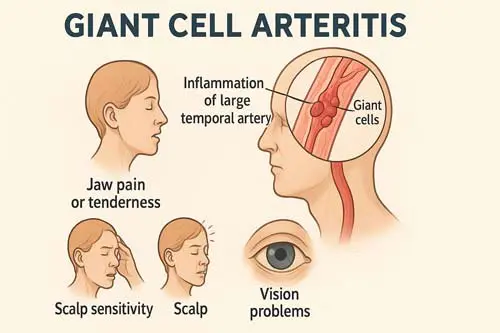

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) stands as a medical paradox—a disease that simultaneously demands immediate, aggressive intervention while imposing prolonged therapeutic burden. Giant cell arteritis is characterised by a destructive, granulomatous inflammation of the walls of medium and large-sized arteries. Annual incidence varies between six and 32 cases per 100 000 people worldwide [2], predominantly affecting individuals over 50 years of age. The clinical urgency stems from the devastating potential for irreversible vision loss, while the therapeutic challenge lies in the necessity for extended high-dose corticosteroid treatment with its attendant complications.

For decades, the cornerstone of GCA management has been high-dose glucocorticoids, which effectively control acute inflammation but carry substantial long-term risks. GCs are therapeutically effective in GCA and the prednisone dosage was reduced to physiologic levels in three-fourths of the patients within 1 year. However, most patients developed serious adverse side effects related to GCs, indicating that less toxic therapeutic measures are needed [3]. This therapeutic dilemma has driven decades of research seeking effective steroid-sparing alternatives.

The landscape of GCA treatment underwent a seismic shift with the introduction of tocilizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting the interleukin-6 receptor. Two randomized controlled trials recently showed the efficacy of the IL-6 receptors inhibitor monoclonal antibody TCZ for the induction and maintenance of remission in patients with new-onset and relapsing GCA. Furthermore, addition of TCZ to prednisone led to a reduction in the cumulative prednisone doses required to control GCA [4]. The emergence of tocilizumab has raised fundamental questions about the future role of corticosteroids in GCA management.

This analytical exploration addresses a central question facing contemporary rheumatology and vasculitis specialists: Does the proven efficacy of tocilizumab herald the obsolescence of traditional steroid-based treatment paradigms in giant cell arteritis? This inquiry extends beyond simple therapeutic substitution to encompass broader considerations of optimal patient care, resource allocation, and the evolution of precision medicine in autoimmune disease management.

Through systematic examination of clinical evidence, mechanistic understanding, real-world implementation challenges, and economic implications, we aim to provide a nuanced analysis that acknowledges both the transformative potential of IL-6 inhibition and the enduring clinical realities that may preserve important roles for corticosteroids in GCA management. This analysis is particularly relevant as healthcare systems worldwide grapple with integrating expensive biologic therapies while maintaining treatment accessibility and optimizing patient outcomes.

The Historical Context and Steroid Era

The treatment of giant cell arteritis has been inextricably linked with corticosteroid therapy since the mid-20th century. Glucocorticosteroids are the cornerstone of treatment of giant cell arteritis. An initial dose of prednisone or its equivalent of at least 40-60mg per day as single or divided dose is usually adequate [5]. This approach, while effective in preventing catastrophic complications such as blindness, established a treatment paradigm characterized by prolonged exposure to high-dose systemic corticosteroids.

The historical reliance on steroids emerged from their rapid anti-inflammatory effects and proven ability to prevent ischemic complications. Glucocorticosteroids may prevent, but usually do not reverse, visual loss. A treatment course of 1-2 years is often required [6] [7]. However, this treatment duration proved problematic, as some patients have a more chronic-relapsing course and may require low doses of glucocorticosteroids for several years. Glucocorticosteroid-related adverse events are common [8].

The scope of corticosteroid-related morbidity in GCA patients became increasingly apparent through longitudinal studies. Ninety patients with giant cell arteritis were followed up 9-16 years (median 11.3 years) after diagnosis. The mean duration of corticosteroid therapy was 5.8 years (range 0-12.8 years). Together, the patients had received corticosteroids for 492 patient-years [9]. These studies revealed the true burden of prolonged steroid exposure, with five years after diagnosis, 43% of the patients were on corticosteroid therapy. After 9 years, 15 of 60 surviving patients (25%) were still being treated with 1.25-10 mg of prednisolone daily (median dose 5 mg) [10].

The adverse event profile associated with prolonged corticosteroid use in GCA patients has been extensively documented. In a survey of long-term CS users, however, 90% reported ≥1 adverse event (AE) attributed to this treatment [11]. More specific analysis revealed that in a 15 year survey from Israel, 58% of patients with GCA had serious GC-related complications, and these complications were more frequent among patients over 70 years of age and among those given an initial dose of prednisone of more than 40 mg per day [12].

The most frequently observed adverse effects encompassed multiple organ systems. The earliest side effects were hypertension, diabetes [13], alongside osteoporosis, infections, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and cataracts. These complications were particularly concerning given that GCA predominantly affects an elderly population already at risk for many of these conditions.

Efforts to identify effective steroid-sparing agents began in earnest during the 1990s. In studies on immunosuppressant agents, methotrexate has been used as a glucocorticosteroid-sparing drug with conflicting results. This drug may, however, be given to patients who need high doses of glucocorticosteroids to control active disease and who have serious side effects [14]. However, methotrexate’s efficacy remained modest, and other conventional immunosuppressive agents showed limited benefit.

The failure of conventional steroid-sparing approaches led to investigation of biologic therapies. Although tumour necrosis factor inhibitors have failed to demonstrate efficacy in giant cell arteritis, and the benefits offered by methotrexate seem to be modest, recent phase 2 clinical trials with abatacept, mavrilimumab, and secukinumab have shown encouraging results [15]. Despite these developments, tocilizumab is the only medication with confirmed efficacy in a phase 3 clinical trial in terms of remission maintenance, glucocorticoid-sparing, and health-related quality of life improvement [16].

The Mechanistic Revolution: Understanding IL-6 in Giant Cell Arteritis

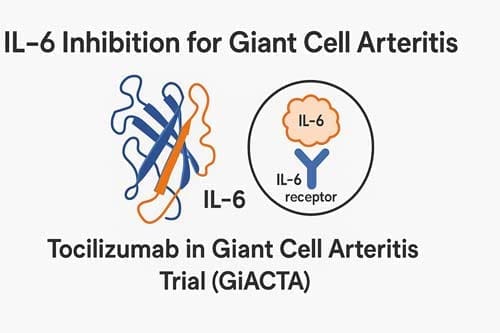

The breakthrough in understanding GCA pathophysiology that ultimately led to tocilizumab’s development centered on the recognition of interleukin-6’s central role in disease pathogenesis. Interleukin-6 induces acute phase responses and has a central role in the pathogenesis of giant cell arteritis. Serum and tissue samples of patients with this disorder show increased concentrations of interleukin-6 [17]. This discovery provided the mechanistic foundation for targeted therapeutic intervention.

The IL-6 pathway’s involvement in GCA extends beyond simple inflammatory amplification. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) plays a role in the pathophysiology of GCA. This review covers recent advances in the treatment of GCA with tocilizumab (TCZ), which specifically binds to both soluble and membrane-bound IL-6R and inhibits IL-6R-mediated signaling [18]. This comprehensive inhibition addresses multiple aspects of GCA pathophysiology, including immune cell activation, acute phase response generation, and vascular inflammation propagation.

Recent mechanistic studies have provided deeper insights into tocilizumab’s effects at the tissue level. Tocilizumab decreased expression/phosphorylation of STAT3 and reduced expression of STAT3-dependent molecules including suppressor of cytokine signalling 3, CCL-2, and ICAM-1 in cultured GCA-involved arteries and patients’ peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) [19]. These molecular effects translate to functional improvements in vascular inflammation control.

However, the mechanistic story is more complex than simple IL-6 blockade. In some specimens, tocilizumab increased STAT1 phosphorylation and expression of STAT1-dependent chemokines including CXCL9 and CXCL10. About half of the patients may activate alternative inflammatory pathways in their lesions as a potential escape mechanism to tocilizumab that deserves further investigation [20] [21]. This finding suggests that while IL-6 inhibition is highly effective, it may not completely eliminate all inflammatory pathways in GCA.

The clinical implications of this mechanistic understanding are profound. Collectively the data suggest that IL-6 blockade using tocilizumab qualifies as a therapeutic option to induce rapid remission in large vessel vasculitides [22]. Early case series demonstrated remarkable clinical responses, with all patients achieved a rapid and complete clinical response and normalisation of the acute phase proteins [23].

The mechanistic rationale for tocilizumab extends to its effects on corticosteroid sensitivity. Tocilizumab, used to treat rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, is a humanised immunoglobulin G1 kappa monoclonal antibody that blocks signalling by binding to the alpha chain of the human interleukin-6 receptor [24]. By interrupting IL-6 signaling, tocilizumab potentially addresses one of the fundamental drivers of corticosteroid resistance in some GCA patients.

The GiACTA Trial: A Paradigm Shift

The Giant Cell Arteritis Actemra (GiACTA) trial represents a watershed moment in GCA therapeutics, providing the definitive evidence base for tocilizumab’s efficacy and establishing new treatment paradigms. The GiACTA trial is a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study designed to test the ability of tocilizumab (TCZ), an interleukin (IL)-6 receptor antagonist, to maintain disease remission in patients with giant cell arteritis (GCA) [25] [26].

The trial design addressed fundamental questions about both tocilizumab efficacy and optimal steroid tapering strategies. In this 1-year trial, we randomly assigned 251 patients, in a 2:1:1:1 ratio, to receive subcutaneous tocilizumab (at a dose of 162 mg) weekly or every other week, combined with a 26-week prednisone taper, or placebo combined with a prednisone taper over a period of either 26 weeks or 52 weeks [27]. This design allowed direct comparison of tocilizumab plus short-term steroids against traditional prolonged steroid regimens.

The primary endpoint results demonstrated tocilizumab’s clear superiority. The primary outcome was the rate of sustained glucocorticoid-free remission at week 52 in each tocilizumab group as compared with the rate in the placebo group that underwent the 26-week prednisone taper [28]. The findings were striking: patients receiving tocilizumab achieved sustained remission rates that far exceeded those achieved with steroids alone, even when steroids were continued for the full 52 weeks.

The trial’s impact extended beyond simple efficacy demonstration to establish new concepts in GCA management. Relapse-free survival was achieved in 17 (85%) patients in the tocilizumab group and two (20%) in the placebo group by week 52 (risk difference 65%, 95% CI 36–94; p=0·0010) [29]. These results fundamentally challenged the assumption that GCA required prolonged high-dose corticosteroid therapy.

Importantly, the trial demonstrated impressive steroid-sparing effects. The mean survival-time difference to stop glucocorticoids was 12 weeks in favour of tocilizumab (95% CI 7–17; p<0·0001), leading to a cumulative prednisolone dose of 43 mg/kg in the tocilizumab group versus 110 mg/kg in the placebo group (p=0·0005) after 52 weeks [30]. This dramatic reduction in cumulative steroid exposure represented a potential solution to the longstanding problem of steroid-related morbidity in GCA.

The trial’s success across different GCA phenotypes was particularly noteworthy. The randomized, placebo (PBO)-controlled GiACTA trial demonstrated the efficacy and safety of tocilizumab (TCZ) in patients with giant cell arteritis (GCA). The present study evaluated the efficacy of TCZ in patients with GCA presenting with polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) symptoms only, cranial symptoms only or both PMR and cranial symptoms in the GiACTA trial [31]. This broad efficacy supported tocilizumab’s utility across the spectrum of GCA presentations.

Post-hoc analyses revealed important insights about patient selection and treatment duration. Of 251 patients, 119 (47%) had newly diagnosed and 132 (53%) had relapsing GCA. Results: Of 251 patients, 119 (47%) had newly diagnosed and 132 (53%) had relapsing GCA [32] [33]. The efficacy was demonstrated in both newly diagnosed and relapsing patients, suggesting broad applicability.

Long-term Outcomes and Real-World Evidence

The long-term extension of the GiACTA trial provided crucial insights into the durability of tocilizumab’s effects and addressed questions about optimal treatment duration. The combination of tocilizumab plus a glucocorticoid taper is effective in maintaining clinical remission without requiring additional glucocorticoid therapy in patients with giant cell arteritis, as shown in part one of the Giant Cell Arteritis Actemra (GiACTA) trial. A substantial proportion of patients with giant cell arteritis who achieve remission with tocilizumab treatment can maintain tocilizumab-free and glucocorticoid-free remission for another 2 years after stopping treatment [34].

However, the long-term follow-up also revealed important limitations. The recent publication of the open-label extension phase of the GiACTA trial did not help to mitigate this uncertainty, since 58% of patients treated with a 12-month course of weekly tocilizumab had a disease flare in the 2 years following therapy suspension [35]. This finding raised important questions about optimal treatment duration and discontinuation strategies.

Real-world evidence has largely confirmed the trial findings while revealing additional practical considerations. Real-life patients undergoing TCZ were older with longer disease duration and higher values of ESR and had received conventional immunosuppressive therapy (mainly methotrexate) more commonly than those included in the GiACTA trial. Despite clinical differences, TCZ was equally effective in both GiACTA trial and clinical practice patients [36] [37]. This validation was crucial for establishing tocilizumab’s effectiveness in routine clinical practice.

However, real-world studies also identified important safety considerations. However, serious infections were more commonly observed in GCA patients recruited from the clinical practice [38]. This finding highlighted the importance of careful patient selection and monitoring in routine practice, where patients may have more comorbidities than those enrolled in clinical trials.

Several real-world studies have examined tocilizumab tapering strategies, recognizing that abrupt discontinuation may not be optimal. Tocilizumab was administered weekly for the first 12 months, every-other-week for an additional 12 months, then discontinued. Following the approval of tocilizumab (TCZ) for giant cell arteritis (GCA), recent studies have shown a high relapse frequency after abrupt discontinuation of TCZ. However, a thorough exploration of TCZ tapering compared to abrupt discontinuation has never been undertaken [39] [40].

Long-term safety data from extended follow-up has generally been reassuring. Long-term TCZ treatment was associated with remission maintenance in most patients with GCA. The estimated relapse rate by 18 months after TCZ discontinuation was 47.3% [41]. While relapse rates remain significant, the overall safety profile supports continued use in appropriate patients.

Tocilizumab vs. Traditional Therapies: Comparative Efficacy

Direct comparisons between tocilizumab and traditional steroid-sparing agents have provided important insights into relative therapeutic value. The most extensive comparative data exists for tocilizumab versus methotrexate, the traditional first-line steroid-sparing agent.

Thirty-one out of 112 (27.7%) patients were treated with TCZ (162 mg/week), while 81/112 (72.3%) patients received MTX (up to 20 mg/week) as a GC-sparing agent. At month 6 after GCA onset, 5/31 (16.1%) patients in TCZ group and none in MTX group were in GC-free sustained remission (p value = 0.001) [42]. This real-world comparison demonstrated tocilizumab’s superior ability to achieve steroid-free remission within a clinically meaningful timeframe.

Historical data on methotrexate efficacy provides context for tocilizumab’s superior performance. In this large single-institution cohort, the addition of MTX to GC decreased the rate of subsequent relapse by nearly 2-fold compared to patients taking GC alone. MTX may be considered as adjunct therapy in patients with GCA to decrease the risk of further relapse events [43]. While methotrexate shows modest benefits, its effect size is considerably smaller than that observed with tocilizumab.

Meta-analyses have confirmed the superior efficacy of tocilizumab compared to other interventions. Tocilizumab, IV GC and methotrexate notably improved the likelihood of being relapse free with relative risks and 95% confidence intervals of 3.54 (2.28, 5.51), 5.11 (1.39, 18.81) and 1.54 (1.02, 2.30); respectively. Conclusion: Tocilizumab, IV GC and methotrexate improve the likelihood of being relapse-free in subjects with GCA. The magnitude of tocilizumab’s effect substantially exceeds that of methotrexate.

A systematic review examining steroid-sparing strategies reached similar conclusions. Tocilizumab is the only drug that reduces the relapse rate in giant cell arteritis. Tocilizumab seems to reduce the relapse rate in GCA at week 52 but the quality of evidence was moderate. No other molecule has shown efficacy [44] [45]. This assessment underscores tocilizumab’s unique position among GCA therapeutics.

The comparative efficacy extends to practical clinical outcomes beyond relapse prevention. Studies examining time to steroid discontinuation have shown marked advantages for tocilizumab. In real-world settings, tocilizumab consistently enables faster achievement of steroid-free remission compared to methotrexate or steroid monotherapy.

Safety Considerations and Adverse Event Profiles

The safety profile of tocilizumab in GCA patients has been extensively studied, revealing both reassuring findings and important considerations for clinical practice. The most comprehensive safety data comes from the GiACTA trial and its extensions, supplemented by real-world surveillance studies.

In controlled trials, tocilizumab’s safety profile has been generally favorable. The profile of adverse events was balanced across treatment groups and no safety concerns were raised during the trial [46]. However, longer-term follow-up and real-world experience have identified specific areas requiring attention.

The most commonly reported adverse events with tocilizumab therapy include hematological abnormalities and infections. However, this study confirms that the most frequent adverse events are hematological abnormalities (e.g. neutropenia and thrombocytopenia), infections, increased transaminases, and injection-related reactions [47]. These findings align with tocilizumab’s known safety profile from other indications.

Real-world studies have provided important context about adverse event rates in routine practice. The relatively high frequency of adverse events in this study implies that attention must be provided to safety before the initiation of TCZ treatment in routine care [48]. This observation emphasizes the importance of careful patient selection and monitoring protocols.

Specific safety concerns have emerged from extended follow-up studies. Overall, four (13%) participants developed a serious adverse event, including one related or probably related to prednisone exclusively, two related or probably related to tocilizumab exclusively, and one related or probably related to prednisone, tocilizumab, or both [49]. While the overall rate of serious adverse events remains acceptable, the need for vigilant monitoring is clear.

Comparative safety assessments suggest that tocilizumab’s safety profile may be favorable compared to prolonged high-dose corticosteroids, particularly in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities. The avoidance of prolonged steroid exposure eliminates many of the most serious long-term complications associated with traditional GCA treatment.

Infection risk, a particular concern with any immunosuppressive therapy, requires careful consideration. While tocilizumab increases infection risk, this must be balanced against the infection risk associated with prolonged high-dose corticosteroids. The overall infection profile may be more favorable with tocilizumab due to the ability to minimize steroid exposure.

Economic Considerations and Cost-Effectiveness

The economic implications of tocilizumab adoption in GCA management present complex considerations balancing drug acquisition costs against potential savings from reduced complications and healthcare utilization. Although the clinical effects are well described in GCA, the cost-effectiveness of the use of tocilizumab in GCA is ill defined. The purpose of this study was to determine the cost-effectiveness of tocilizumab in GCA compared with prednisone alone [50].

Cost-effectiveness analyses have yielded variable results depending on methodology and perspective. The difference in cost between the 2 therapy types is directly related to tocilizumab therapy duration and inversely related to the number or severity of steroid side effects. Patients with GCA who require a shorter duration of steroid therapy and are at risk for a high number of side effects from steroid use may be potential candidates for tocilizumab therapy, from an economic perspective [51].

The economic calculation is complicated by the substantial costs associated with steroid-related complications. Prolonged high-dose corticosteroid therapy is associated with increased healthcare utilization due to complications including fractures, infections, diabetes, cardiovascular events, and hospitalizations. These costs may offset the higher acquisition cost of tocilizumab, particularly in high-risk patients.

Healthcare system perspectives on tocilizumab adoption vary remarkably. Tocilizumab (TCZ) is increasingly used as a steroid-sparing agent in giant cell arteritis (GCA), but there are strict Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) restrictions for its use in Australia. Patients who do not meet the PBS criteria can obtain TCZ through public hospital individual patient use (IPU) schemes which may not be universally accessible [52]. These access restrictions reflect ongoing economic concerns about widespread tocilizumab adoption.

The cost-effectiveness equation may be particularly favorable in certain patient subgroups. Elderly patients with multiple comorbidities who are at high risk for steroid-related complications may represent the most cost-effective target population for tocilizumab therapy. Conversely, younger patients with newly diagnosed disease who might successfully taper steroids without complications may not demonstrate favorable cost-effectiveness ratios.

Long-term economic modeling must also consider the potential for tocilizumab to prevent some of the most costly complications of GCA, including blindness, stroke, and aortic complications. While these events are relatively rare, their prevention could greatly impact long-term cost-effectiveness calculations.

Clinical Practice Integration and Treatment Algorithms

The integration of tocilizumab into routine GCA management has necessitated the development of new treatment algorithms and decision-making frameworks. Clinical guidelines and expert recommendations have evolved to incorporate tocilizumab while maintaining steroid therapy’s critical roles.

Current recommendations generally position tocilizumab as a steroid-sparing agent rather than a complete steroid replacement. High dose glucocorticoid therapy (40–60 mg/day prednisone-equivalent) should be initiated immediately for induction of remission in active giant cell arteritis (GCA) or Takayasu arteritis (TAK). We recommend adjunctive therapy in selected patients with GCA (refractory or relapsing disease, presence of an increased risk for glucocorticoid-related adverse events or complications) using tocilizumab [53].

The selection criteria for tocilizumab initiation reflect practical considerations about cost-effectiveness and patient characteristics. Presence of or increased risk for steroid-related adverse effects, clinical relapse, or persistence of disease activity were the requirements to initiation tocilizumab, as advocated by the most recent EULAR recommendations [54]. These criteria emphasize tocilizumab’s role in patients who have failed or are inappropriate for standard steroid therapy.

Treatment duration remains an area of ongoing investigation and clinical judgment. Despite adoption of tocilizumab into clinical management strategies for GCA, there remains uncertainty regarding treatment duration and the optimal approach to medication suspension. The recent publication of the open-label extension phase of the GiACTA trial did not help to mitigate this uncertainty, since 58% of patients treated with a 12-month course of weekly tocilizumab had a disease flare in the 2 years following therapy suspension [55].

Practical protocols for tocilizumab tapering have emerged from clinical experience. Tocilizumab was administered weekly for the first 12 months, every-other-week for an additional 12 months, then discontinued. Tocilizumab tapered over a two-year period was effective to induce and maintain remission in GCA [56] [57]. However, even with tapering strategies, significant relapse rates persist after discontinuation.

The role of combination therapy with conventional agents remains under investigation. Relapses on tocilizumab were managed with temporary increases in systemic glucocorticoids or addition of methotrexate [58]. This suggests that tocilizumab does not eliminate the need for other therapeutic approaches in managing complex cases.

Exploring Ultra-Short Steroid Protocols

One of the most intriguing developments in GCA management has been the investigation of ultra-short steroid protocols combined with tocilizumab. These approaches aim to minimize steroid exposure while maintaining efficacy through early IL-6 inhibition.

A particularly innovative approach was examined in a proof-of-concept study. Even after the approval of tocilizumab, substantial glucocorticoid exposure (usually ≥6 months) and toxicity continue to be important problems for patients with giant cell arteritis. We aimed to assess the outcomes of a group of patients with giant cell arteritis treated with tocilizumab in combination with 8 weeks of prednisone [59] [60].

The results of ultra-short steroid protocols have been promising. All patients entered remission within 4 weeks from baseline. 23 (77%) of 30 patients were in sustained prednisone-free remission at week 52 and seven (23%) patients relapsed, with a mean time to relapse of 15·8 weeks (SD 14·7) [61]. These findings suggest that effective GCA control may be achievable with much shorter steroid courses than traditionally employed.

The implications of successful ultra-short steroid protocols are profound. This proof-of-concept study suggests that tocilizumab in combination with 8 weeks of prednisone might be an efficacious strategy for inducing and maintaining disease remission for at least 1 year in patients with giant cell arteritis, avoiding the need for and complications of prolonged glucocorticoid treatment. A randomised controlled trial is required to confirm these findings and formally assess the glucocorticoid-related toxicity associated with 8 weeks of prednisone in comparison with current standard-of-care glucocorticoid tapers [62].

Even more aggressive approaches have been investigated, including tocilizumab monotherapy after ultra-short high-dose intravenous steroids. A 2021 single-arm, proof-of-concept trial on 18 newly diagnosed patients with giant cell arteritis showed that tocilizumab monotherapy after an ultra-short glucocorticoid treatment (500 mg/day methylprednisolone intravenously for 3 consecutive days) induced remission in 14 (78%) patients, but this result occurred after a long treatment duration (mean number of weeks 11·1 [95% CI 8·3–13·9]), with permanent vision loss occurring in one patient [63].

These ultra-short protocols represent the most aggressive attempt to minimize steroid exposure while maintaining efficacy. However, they also highlight the continued importance of some steroid therapy in GCA management, even in the tocilizumab era.

Future Directions and Emerging Therapies

While tocilizumab has transformed GCA management, research continues into additional therapeutic targets and optimization strategies. The understanding that not all patients respond optimally to IL-6 inhibition has driven investigation of alternative pathways and combination approaches.

Emerging therapeutic targets include other cytokine pathways and cellular mechanisms involved in GCA pathogenesis. Although tumour necrosis factor inhibitors have failed to demonstrate efficacy in giant cell arteritis, and the benefits offered by methotrexate seem to be modest, recent phase 2 clinical trials with abatacept, mavrilimumab, and secukinumab have shown encouraging results [64]. These agents target different aspects of the immune response and may offer alternatives or adjuncts to IL-6 inhibition.

JAK inhibitors represent another emerging therapeutic class. Effectiveness of janus kinase inhibitors in relapsing giant cell arteritis in real-world clinical practice and review of the literature [65] [66] suggests potential utility for these agents in refractory cases or as alternative approaches to biological therapy.

The concept of personalized medicine in GCA is beginning to emerge, with recognition that different patients may benefit from different therapeutic approaches. Biomarker development may eventually allow clinicians to predict which patients will respond best to specific therapies, optimizing both efficacy and cost-effectiveness.

Treatment sequencing strategies are also evolving. The Meteoritics Trial: efficacy of methotrexate after remission-induction with tocilizumab and glucocorticoids in giant cell arteritis-study protocol for a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase II study [67] represents an innovative approach to using different agents in sequence to optimize long-term outcomes.

The Persistent Role of Corticosteroids

Despite tocilizumab’s proven efficacy, several factors suggest that corticosteroids will retain important roles in GCA management for the foreseeable future. These roles may be more limited and targeted than in the past, but they remain clinically essential.

Emergency management of GCA continues to require immediate high-dose corticosteroids. Giant cell arteritis (GCA) remains a medical emergency due to the threat of permanent sight loss. High-dose glucocorticoids (GCs) are effective in inducing remission in the majority of patients, however, relapses are common which lengthen GC therapy [68] [69]. The rapid anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroids remain unmatched for preventing irreversible ischemic complications.

Economic and access considerations also preserve an important role for corticosteroids. Not all patients have access to tocilizumab due to cost, insurance restrictions, or healthcare system limitations. Further studies demonstrating that TCZ is comparatively more effective than prednisolone monotherapy, as well as cost-effective, are needed to substantiate the rationale for expanding PBS approval criteria [70] [71]. This access challenge ensures that corticosteroids remain the primary therapy for many patients globally.

Contraindications to tocilizumab also necessitate continued steroid use. Patients with active infections, severe immunodeficiency, or other contraindications to biological therapy may require traditional steroid-based management approaches.

The combination of tocilizumab with corticosteroids appears to be the optimal approach in many situations. Tocilizumab can be used to manage relapses, but it remains prudent to include prednisone for patients who experience relapse because of the risk for vision loss. For patients who experience relapse, tocilizumab can be used to manage relapses, but it remains prudent to include prednisone for patients who experience relapse because of the risk for vision loss [72] [73].

Critical Analysis and Limitations

While the evidence for tocilizumab’s efficacy in GCA is compelling, several important limitations and considerations must be acknowledged in evaluating whether steroids are becoming obsolete.

The relapse rates following tocilizumab discontinuation remain substantial. The estimated relapse rate by 18 months after TCZ discontinuation was 47.3% [74]. This high relapse rate suggests that tocilizumab may be suppressing rather than curing the underlying disease process, similar to corticosteroids.

Long-term safety data remains limited compared to the decades of experience with corticosteroids. While short-term safety appears acceptable, the consequences of prolonged IL-6 inhibition in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities require continued surveillance.

The mechanistic understanding reveals that tocilizumab may not address all pathways involved in GCA. About half of the patients may activate alternative inflammatory pathways in their lesions as a potential escape mechanism to tocilizumab that deserves further investigation [75]. This finding suggests that complete steroid replacement may not be achievable in all patients.

Cost-effectiveness remains questionable in many healthcare settings, particularly for patients at lower risk for steroid-related complications. The substantial cost differential between tocilizumab and corticosteroids may limit widespread adoption even where clinical benefits are clear.

Treatment duration optimization remains unresolved. However, the duration of tocilizumab treatment in reported clinical trials has been arbitrary, and the optimal length of tocilizumab therapy and the effect after 1 year of treatment are not known [76]. This uncertainty complicates both clinical decision-making and economic calculations.

Synthesis and Future Perspectives

The question of whether steroids are becoming obsolete in GCA management requires a nuanced answer that acknowledges both the transformative impact of tocilizumab and the enduring clinical realities that preserve important roles for corticosteroids.

Tocilizumab has fundamentally changed GCA treatment paradigms by demonstrating that sustained remission can be achieved with dramatically reduced steroid exposure. Tocilizumab, received weekly or every other week, combined with a 26-week prednisone taper was superior to either 26-week or 52-week prednisone tapering plus placebo with regard to sustained glucocorticoid-free remission in patients with giant-cell arteritis [77] [78]. This represents a genuine therapeutic revolution that has improved outcomes for many patients.

However, complete steroid obsolescence appears unlikely for several reasons. The immediate need for rapid anti-inflammatory effects in emergency situations, economic constraints, access limitations, and the substantial relapse rates following tocilizumab discontinuation all support continued steroid utility. The future likely lies in optimized combination strategies that maximize the benefits of both therapeutic approaches while minimizing their respective limitations.

The evolution toward more personalized treatment approaches may help resolve current uncertainties. Patient selection algorithms that identify those most likely to benefit from tocilizumab, optimal treatment duration protocols, and effective discontinuation strategies will refine the roles of both tocilizumab and corticosteroids.

The results of this study support the principle that continuous indefinite treatment with immunosuppressive drugs is not required to maintain disease control for all patients with giant cell arteritis. Glucocorticoids still have an important role in managing giant cell arteritis [79]. This perspective suggests that the future of GCA management lies not in the obsolescence of steroids but in their more judicious and targeted use as part of comprehensive treatment strategies.

Conclusion

The introduction of tocilizumab has ushered in a new era of giant cell arteritis management, fundamentally challenging traditional steroid-centric treatment paradigms. The evidence unequivocally demonstrates tocilizumab’s superior efficacy in maintaining sustained remission while dramatically reducing cumulative steroid exposure and associated morbidity. This represents genuine therapeutic progress that has improved outcomes for many patients with this challenging condition.

However, the question of steroid obsolescence requires a more nuanced response than simple replacement paradigms might suggest. While tocilizumab has reduced the role of prolonged high-dose corticosteroids, it has not eliminated the need for steroids entirely. Emergency management, economic constraints, access limitations, and the biology of GCA itself preserve important roles for corticosteroid therapy.

The optimal future approach likely involves integrated treatment strategies that leverage the strengths of both therapeutic modalities. Ultra-short steroid protocols combined with tocilizumab represent promising approaches to minimize steroid toxicity while maintaining efficacy. However, the substantial relapse rates following tocilizumab discontinuation suggest that neither approach alone provides a complete solution to GCA management challenges.

Several key areas require continued investigation to optimize GCA treatment strategies. Long-term safety surveillance of tocilizumab in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities remains essential. Cost-effectiveness studies in diverse healthcare settings will inform access and utilization policies. Treatment duration optimization and effective discontinuation strategies need development. Finally, the identification of biomarkers to guide personalized treatment selection could maximize both clinical outcomes and resource utilization.

The transformation of GCA management exemplifies the broader evolution of medicine toward precision approaches that balance efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness. While tocilizumab has not rendered steroids obsolete, it has fundamentally altered their role and opened new possibilities for improved patient care. The continued refinement of these approaches, combined with emerging therapeutic targets and personalized medicine strategies, promises further advances in managing this complex condition.

The ultimate goal remains clear: achieving sustained disease control with minimal treatment-related morbidity in a cost-effective manner. Tocilizumab has brought us significantly closer to this goal, but the journey toward optimal GCA management continues to evolve. The future lies not in choosing between steroids and tocilizumab, but in learning how to use both approaches most effectively to serve patients’ best interests.

References:

[1] Tocilizumab in giant cell arteritis: differences between the GiACTA trial and a multicentre series of patients from the clinical practice – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32441643/

[2] Tocilizumab for the treatment of giant cell arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29676602/

[3] Serious adverse effects associated with glucocorticoid therapy in patients with giant cell arteritis (GCA): A nested case-control analysis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28040244/

[4] Tocilizumab for the treatment of giant cell arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29676602/

[5] Deterioration of giant cell arteritis with corticosteroid therapy – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10768635/

[6] Deterioration of giant cell arteritis with corticosteroid therapy – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10768635/

[7] Deterioration of giant cell arteritis with corticosteroid therapy – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10768635/

[8] Deterioration of giant cell arteritis with corticosteroid therapy – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10768635/

[9] Treatment for giant cell arteritis with 8 weeks of prednisone in combination with tocilizumab: a single-arm, open-label, proof-of-concept study – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38251564/

[10] Treatment for giant cell arteritis with 8 weeks of prednisone in combination with tocilizumab: a single-arm, open-label, proof-of-concept study – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38251564/

[11] Tocilizumab for induction and maintenance of remission in giant cell arteritis: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0140673616005602

[12] Long-term effect of tocilizumab in patients with giant cell arteritis: open-label extension phase of the Giant Cell Arteritis Actemra (GiACTA) trial – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2665991321000382

[13] Long-term effect of tocilizumab in patients with giant cell arteritis: open-label extension phase of the Giant Cell Arteritis Actemra (GiACTA) trial – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2665991321000382

[14] Deterioration of giant cell arteritis with corticosteroid therapy – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10768635/

[15] Glucocorticoid therapy in giant cell arteritis: duration and adverse outcomes – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14558057/?dopt=Abstract

[16] Glucocorticoid therapy in giant cell arteritis: duration and adverse outcomes – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14558057/?dopt=Abstract

[17] Tocilizumab for the treatment of giant cell arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29676602/

[18] Treatment for giant cell arteritis with 8 weeks of prednisone in combination with tocilizumab: a single-arm, open-label, proof-of-concept study – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2665991323002655

[19] Profile of tocilizumab and its potential in the treatment of giant cell arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29416384/

[20] Profile of tocilizumab and its potential in the treatment of giant cell arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29416384/

[21] Profile of tocilizumab and its potential in the treatment of giant cell arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29416384/

[22] [Efficacy and tolerance of tocilizumab for corticosteroid sparing in giant cell arteritis and aortitis: Experience of Nimes University Hospital about eleven patients] – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29221884/

[23] [Efficacy and tolerance of tocilizumab for corticosteroid sparing in giant cell arteritis and aortitis: Experience of Nimes University Hospital about eleven patients] – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29221884/

[24] Tocilizumab for the treatment of giant cell arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29676602/

[25] Tocilizumab vs placebo for the treatment of giant cell arteritis with polymyalgia rheumatica symptoms, cranial symptoms or both in a randomized trial – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0049017221000366

[26] Tocilizumab vs placebo for the treatment of giant cell arteritis with polymyalgia rheumatica symptoms, cranial symptoms or both in a randomized trial – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0049017221000366

[27] Tocilizumab in giant cell arteritis: differences between the GiACTA trial and a multicentre series of patients from the clinical practice – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32441643/

[28] Tocilizumab in giant cell arteritis: differences between the GiACTA trial and a multicentre series of patients from the clinical practice – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32441643/

[29] Efficacy of Methotrexate in Real-world Management of Giant Cell Arteritis: A Case-control Study – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30647171/

[30] Efficacy of Methotrexate in Real-world Management of Giant Cell Arteritis: A Case-control Study – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30647171/

[31] Trial of Tocilizumab in Giant-Cell Arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28745999/

[32] Long-term effect of tocilizumab in patients with giant cell arteritis: open-label extension phase of the Giant Cell Arteritis Actemra (GiACTA) trial – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38279390/

[33] Long-term effect of tocilizumab in patients with giant cell arteritis: open-label extension phase of the Giant Cell Arteritis Actemra (GiACTA) trial – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38279390/

[34] Design of the tocilizumab in giant cell arteritis trial – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23653652/

[35] Long-term corticosteroid treatment in giant cell arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3812030/

[36] Newly diagnosed vs. relapsing giant cell arteritis: Baseline data from the GiACTA trial – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27998620/

[37] Newly diagnosed vs. relapsing giant cell arteritis: Baseline data from the GiACTA trial – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27998620/

[38] Newly diagnosed vs. relapsing giant cell arteritis: Baseline data from the GiACTA trial – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27998620/

[39] Effectiveness of a two-year tapered course of tocilizumab in patients with giant cell arteritis: A single-centre prospective study – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0049017223000148

[40] Effectiveness of a two-year tapered course of tocilizumab in patients with giant cell arteritis: A single-centre prospective study – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0049017223000148

[41] Outcomes during and after long-term tocilizumab treatment in patients with giant cell arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37024237/

[42] Long-term effect of tocilizumab in patients with giant cell arteritis: open-label extension phase of the Giant Cell Arteritis Actemra (GiACTA) trial – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2665991321000382

[43] Efficacy of tocilizumab in refractory giant cell arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22284606/

[44] Effectiveness of a two-year tapered course of tocilizumab in patients with giant cell arteritis: A single-centre prospective study – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0049017223000148

[45] Effectiveness of a two-year tapered course of tocilizumab in patients with giant cell arteritis: A single-centre prospective study – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0049017223000148

[46] Tocilizumab for the treatment of giant cell arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29676602/

[47] Effectiveness of a two-year tapered course of tocilizumab in patients with giant cell arteritis: A single-centre prospective study – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0049017223000148

[48] Effectiveness of a two-year tapered course of tocilizumab in patients with giant cell arteritis: A single-centre prospective study – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0049017223000148

[49] Treatment for giant cell arteritis with 8 weeks of prednisone in combination with tocilizumab: a single-arm, open-label, proof-of-concept study – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2665991323002655

[50] Treatment for giant cell arteritis with 8 weeks of prednisone in combination with tocilizumab: a single-arm, open-label, proof-of-concept study – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2665991323002655

[51] Treatment for giant cell arteritis with 8 weeks of prednisone in combination with tocilizumab: a single-arm, open-label, proof-of-concept study – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2665991323002655

[52] Faster steroid-free remission with tocilizumab compared to methotrexate in giant cell arteritis: a real-life experience in two reference centres – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39093541/

[53] Tocilizumab for induction and maintenance of remission in giant cell arteritis: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26952547/

[54] Long-term corticosteroid treatment in giant cell arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3812030/

[55] Tocilizumab use in giant cell arteritis: comparing Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme eligible and ineligible cases in South Australia – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38953308/

[56] Tocilizumab use in giant cell arteritis: comparing Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme eligible and ineligible cases in South Australia – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38953308/

[57] Tocilizumab use in giant cell arteritis: comparing Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme eligible and ineligible cases in South Australia – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38953308/

[58] Design of the tocilizumab in giant cell arteritis trial – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23653652/

[59] Corticosteroid-related adverse events in patients with giant cell arteritis: A claims-based analysis – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0049017216300610

[60] Corticosteroid-related adverse events in patients with giant cell arteritis: A claims-based analysis – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0049017216300610

[61] Treatment for giant cell arteritis with 8 weeks of prednisone in combination with tocilizumab: a single-arm, open-label, proof-of-concept study – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2665991323002655

[62] Corticosteroid-related adverse events in patients with giant cell arteritis: A claims-based analysis – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0049017216300610

[63] The Cost-Effectiveness of Tocilizumab (Actemra) Therapy in Giant Cell Arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34415267/

[64] Glucocorticoid therapy in giant cell arteritis: duration and adverse outcomes – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14558057/?dopt=Abstract

[65] Outcomes during and after long-term tocilizumab treatment in patients with giant cell arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37024237/

[66] Outcomes during and after long-term tocilizumab treatment in patients with giant cell arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37024237/

[67] Efficacy of tocilizumab in refractory giant cell arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22284606/

[68] Effectiveness of a two-year tapered course of tocilizumab in patients with giant cell arteritis: A single-centre prospective study – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0049017223000148

[69] Effectiveness of a two-year tapered course of tocilizumab in patients with giant cell arteritis: A single-centre prospective study – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0049017223000148

[70] Faster steroid-free remission with tocilizumab compared to methotrexate in giant cell arteritis: a real-life experience in two reference centres – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39093541/

[71] Faster steroid-free remission with tocilizumab compared to methotrexate in giant cell arteritis: a real-life experience in two reference centres – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39093541/

[72] Design of the tocilizumab in giant cell arteritis trial – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23653652/

[73] Design of the tocilizumab in giant cell arteritis trial – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23653652/

[74] Outcomes during and after long-term tocilizumab treatment in patients with giant cell arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37024237/

[75] Profile of tocilizumab and its potential in the treatment of giant cell arteritis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29416384/

[76] Efficacy and safety of steroid-sparing treatments in giant cell arteritis according to the glucocorticoids tapering regimen: A systematic review and meta-analysis – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0953620521001126

[77] Efficacy and tolerance of methotrexate in a real-life monocentric cohort of patients with giant cell arteritis – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S004901722300032X

[78] Efficacy and tolerance of methotrexate in a real-life monocentric cohort of patients with giant cell arteritis – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S004901722300032X

[79] Design of the tocilizumab in giant cell arteritis trial – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23653652/