Study Reveals: Neighborhood Stress Directly Linked to Poor Cognitive Development in Children

Please like and subscribe if you enjoyed this video 🙂

Introduction

Poor cognitive development among children in disadvantaged neighborhoods is a growing public health concern, supported by strong neurobiological evidence. Recent studies involving over 200 children aged 7 to 11 have shown that neighborhood deprivation directly affects brain function. Specifically, children from high-poverty areas demonstrate blunted neural responses to both reward and loss during cognitive tasks, suggesting that chronic environmental stress disrupts typical brain development.

The broader implications of poverty on child development are significant. In 2020, an estimated 6.4 million children in the U.S. lived in neighborhoods with poverty rates exceeding 30%. These environments are consistently linked to lower academic achievement and higher rates of mental health challenges. Neuroimaging research reveals that children from families at or below the poverty line exhibit reductions in gray matter volume—typically 8–9% below age-expected norms. These structural differences particularly impair executive function and core cognitive abilities.

The consequences extend beyond cognition. Children from disadvantaged neighborhoods also show altered amygdala reactivity in response to emotional cues such as fearful or angry faces. This disrupted emotional processing may contribute to difficulties in social-emotional development and behavioral regulation, highlighting how cognitive and emotional development are deeply interconnected and shaped by environmental stressors.

This article reviews current evidence on how neighborhood-level stressors such as poverty, violence, and limited access to resources impact neurodevelopment. It also explores tools used to measure neighborhood disadvantage and identifies protective factors that can buffer against these adverse effects. Among the most effective protective factors is responsive, nurturing parenting, which has been shown to mitigate the harmful impacts of environmental stress on brain development.

While the risks associated with neighborhood deprivation are substantial, these findings also point to actionable pathways for early intervention. Supporting family stability, enhancing caregiving environments, and addressing structural inequities may help promote resilience and improve developmental outcomes for children growing up in disadvantaged settings.

Neighborhood Disadvantage and Its Measurement

Measurement of neighborhood-level influences on child development requires comprehensive tools that capture multiple dimensions of disadvantage. Research indicates that growing up in areas with concentrated disadvantage shapes cognitive outcomes through various pathways beyond individual family circumstances.

Area Deprivation Index (ADI) and Child Opportunity Index (COI)

The Area Deprivation Index (ADI) quantifies neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage at the census block level, incorporating factors such as poverty rates, housing conditions, and employment statistics. Studies utilizing ADI reveal a stark 20-point median difference in overall intelligence between children from neighborhoods with the lowest versus highest levels of deprivation. Moreover, verbal comprehension shows stronger negative associations with neighborhood deprivation compared to working memory, fluid reasoning, and processing speed.

The Child Opportunity Index (COI), specifically designed for measuring neighborhood impacts on children, encompasses 44 indicators across three domains: education, health and environment, and social and economic factors. This multidimensional approach captures resources that support healthy child development, including school quality, access to healthy food, parks, and economic opportunities. Recent research employing COI demonstrates that children in higher-opportunity neighborhoods perform better across all cognitive measures and exhibit larger brain structures, including greater gray matter volume.

Crime Rates and Access to Community Resources

Neighborhood violent crime rates substantially influence child cognitive development through multiple pathways. Children from neighborhoods with elevated crime rates experience constrained mobility, limited access to community resources, and elevated family stress. This restricted access to public spaces and institutions—libraries, recreational centers, parks—directly impacts cognitive stimulation opportunities. Research indicates that neighborhoods with stable access to resources like community centers, libraries, and schools provide greater opportunities for intellectual stimulation and social interaction that support cognitive development.

How Neighborhood Stress Differs from Individual Trauma

Although related, neighborhood stress and individual trauma operate through distinct mechanisms. Neighborhood-level factors such as; concentrated disadvantage, residential instability, and crime increase risk for both childhood trauma exposure and adverse mental health outcomes. Unlike individual traumatic events, neighborhood stress creates a chronic environmental context that affects all residents. A substantial finding reveals how neighborhood-level crime interacts with childhood trauma exposure—emotional neglect combined with high neighborhood crime rates specifically predicted increased major depression symptoms. This cross-level interaction highlights how community conditions can amplify individual vulnerabilities, creating different pathways to poor cognitive outcomes than individual trauma alone.

Neurobiological Pathways Affected by Chronic Stress

Chronic exposure to neighborhood stress triggers substantial neurobiological changes that impact children’s cognitive development through multiple interconnected pathways. Research has documented how these stressors become biologically embedded, altering brain structure and function in ways that affect learning and behavior.

Amygdala Reactivity to Fear and Threat

Neighborhood disadvantage heightens amygdala reactivity to emotional stimuli, especially fear and threat cues. Studies reveal that children exposed to neighborhood violence demonstrate increased right amygdala activation when viewing fearful and angry faces. This heightened amygdala reactivity persists even after stressors are removed, suggesting lasting neurobiological changes. Importantly, amygdala reactivity correlates with fear-potentiated startle responses (r = .56) and explains 15.6% of the unique variance in anxiety above total trauma exposure. This enhanced threat sensitivity represents an adaptive response to dangerous environments that nevertheless carries long-term costs for cognitive processing.

Blunted Reward Positivity (RewP) in EEG Studies

Electroencephalogram (EEG) research shows that neighborhood stress dampens children’s neural responses to rewards. Children from disadvantaged neighborhoods exhibit blunted reward positivity (RewP), a brain response occurring 250-350ms after receiving rewards. This effect proves especially pronounced in children with family histories of depression. Subsequently, lifetime exposure to acute stressors correlates with diminished RewP at follow-up assessments, indicating that neighborhood stress impairs the brain’s ability to process positive outcomes. Hence, poor cognitive development emerges partly through diminished motivation and engagement with learning opportunities.

Cortisol Dysregulation and the HPA Axis

Neighborhood disadvantage disrupts the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, altering cortisol production patterns. Research indicates that disadvantaged neighborhoods are positively associated with salivary cortisol levels in early childhood. Interestingly, concentrated disadvantage predicts cortisol reactivity in boys but not girls, suggesting gender-specific vulnerability. Correspondingly, chronic stress initially increases HPA axis activity followed by eventual downregulation, representing a biological adaptation that may nonetheless increase risk for cognitive impairments and mental health problems.

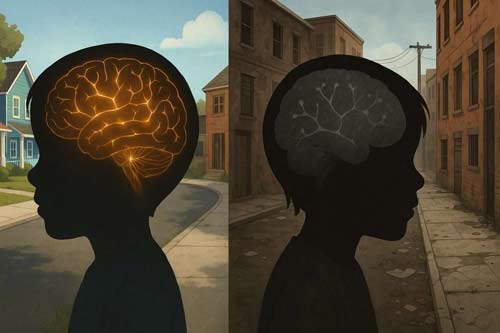

Reduced Gray Matter in Prefrontal Cortex and Hippocampus

Chronic stress from disadvantaged neighborhoods reduces gray matter volume in brain regions crucial for cognitive development. Neuroimaging studies reveal that socioeconomic disadvantage correlates with diminished gray matter in the dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex. Additionally, chronic stress causes loss of spines and dendrites in the prefrontal cortex, undermining the neural foundation for executive functions. These structural alterations mediate the relationship between childhood adversity and trait anxiety, thereby connecting neighborhood stress to poor cognitive outcomes through concrete neural mechanisms.

Risk Amplifiers: Family History and Environmental Chaos

Family and home environment factors amplify the effects of neighborhood disadvantage on cognitive development, creating a compounding risk profile that exceeds their individual contributions. These risk amplifiers operate through distinct yet interconnected pathways, worsening outcomes for vulnerable children.

Parental History of Depression as a Moderator

Children with a parental history of depression face a 2-fold to 5-fold increased risk of developing major depressive disorder and other non-psychotic conditions. This risk extends across generations, children with both parental (G2) and grandparental (G1) depression history show a 13.3% prevalence of depressive disorders compared to only 3.8% in children with neither family history. Indeed, maternal depression disrupts critical parent-child interactions, as depressed mothers demonstrate less emotion and expressivity in language with their babies and make reduced eye contact. These altered interactions directly impact cognitive development, as children of mothers with persistent depressive symptoms show greater neurocognitive impairments than those whose mothers’ symptoms improved within the first three years.

Household Chaos and Noise as Cognitive Stressors

Household chaos characterized by disorganization, lack of routines, and unpredictability independently affects cognitive development beyond socioeconomic factors. Research demonstrates that household chaos correlates with reduced cognitive ability and IQ even after controlling for parent education, home literacy environment, parenting quality, and housing conditions. Notably, the relationship between household chaos and child executive functions is mediated by parental responsiveness. Environmental noise, particularly from transportation sources, compounds these effects, with over half a million European children experiencing impaired reading ability due to environmental noise. Importantly, noise exposure above 70 dB (Lden) was associated with a 32% increase in behavioral difficulties and a 0.27 standard deviation decrease in cognition.

Poor Cognitive Development Signs in Children

Children exposed to these risk amplifiers exhibit distinct cognitive development challenges. Those from chaotic households demonstrate problems with core executive function components including inhibition, working memory, and planning abilities. Rather than merely delaying development, these environmental factors alter developmental trajectories—children exposed to both family risk and environmental chaos show altered developmental patterns that persist even after controlling for socioeconomic factors. Consequently, even modest improvements in environmental conditions can yield measurable cognitive benefits, as evidenced by studies showing cognitive deficits diminish when noise sources are eliminated.

Protective Factors and Resilience Mechanisms

Resilience mechanisms serve as critical counterbalances to neighborhood stress factors, providing pathways for children to develop cognitive abilities even amid adverse environments. These protective elements operate across multiple ecological levels, from family interactions to community structures.

Nurturing Parenting and Emotional Buffering

Nurturing parenting substantially mitigates the detrimental effects of neighborhood disadvantage on child development. Research demonstrates that parental nurturance buffers the relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and exposure to community violence. In studies examining amygdala reactivity, neighborhood disadvantage was associated with greater exposure to community violence only at low and mean levels of parental nurturance (β=.32, p=.001 and β=.18, p=.003, respectively), but not at high levels (β=.04, p=.521). Moreover, exposure to community violence was linked to heightened right amygdala reactivity to threat only at low levels of parental nurturance (β=.21, p=.002). Correspondingly, high-quality caregiving exerts powerful regulatory influences by reducing stress, preventing stress hormone release, and modulating emotional reactivity.

Community Norms Around Violence Prevention

Community cohesion—defined as shared trust, unity, and support within a neighborhood—functions as a protective factor against poor cognitive development. Studies reveal that youth experiencing stressful life events show stronger negative effects in low-cohesion neighborhoods relative to high-cohesion ones. Importantly, rural communities often exhibit higher levels of cohesion compared to urban areas, potentially amplifying this protective effect. The creation of positive community norms around child well-being establishes expectations that support safe, stable, nurturing relationships. These norms become embedded across different levels of community systems, creating broader contexts that foster healthy development.

Early Childhood Interventions and Executive Function Gains

Evidence-based early interventions yield measurable improvements in executive functions essential for cognitive development. Programs like Research-based Developmentally Informed (REDI) and Promoting Alternative Thinking Skills (PATHS) demonstrate that children in intervention classrooms show higher vocabulary, emergent literacy, emotional understanding, social problem solving, and engagement in learning. Similarly, the Chicago School Readiness Project (CSRP) improved classroom emotional climate and reduced behavior problems, with children showing higher levels of executive function. Importantly, these gains in executive function mediated program effects on academic readiness for kindergarten in math, literacy, and language. Even brief mindfulness training produces measurable improvements, with children initially showing poor executive functions demonstrating greater gains in shifting and monitoring abilities.

Conclusion

The evidence is clear: neighborhood disadvantage plays a major role in shaping children’s cognitive development. Chronic exposure to environmental stressors; such as poverty, violence, and social instability has been linked to measurable changes in brain structure and function. Research shows that children growing up in disadvantaged neighborhoods often exhibit heightened amygdala reactivity, blunted reward sensitivity, and reduced prefrontal cortex volume. While these neurobiological adaptations may help children cope with persistent stress, they can impair executive function, emotional regulation, and long-term cognitive growth.

Addressing these challenges requires a multilayered approach across individual, family, and community systems. Protective factors, such as nurturing parenting and strong caregiver-child relationships, can buffer the impact of adversity. For example, high-quality caregiving has been shown to mitigate the cognitive effects of exposure to community violence. Likewise, neighborhood cohesion characterized by mutual trust, shared norms, and collective efficacy can serve as a powerful counterbalance to environmental risk, especially when communities prioritize child safety and well-being.

Early interventions are especially effective. Programs that support executive function, emotional self-regulation, and school readiness such as REDI, PATHS, and CSRP have demonstrated significant improvements in developmental outcomes. These initiatives highlight the importance of timing: early childhood represents a sensitive period when the brain is most responsive to positive environmental input. Intervening during this window can prevent negative developmental trajectories before they become entrenched.

Importantly, the link between neighborhood context and cognitive outcomes is not deterministic. While children in disadvantaged areas face elevated risks, they also possess the potential to thrive when provided with the right support. Practitioners should recognize that behavioral and cognitive challenges in these children often reflect adaptive responses to chronic stress, not inherent deficits.

Future research should explore how genetic predispositions interact with environmental adversity to influence development. In parallel, policies must address the structural inequities that concentrate disadvantage in specific communities, inequities that systematically limit opportunities for healthy cognitive growth.

Ultimately, the neurobiological data underscore an urgent public health mandate: to create environments that support every child’s potential, regardless of zip code. Until structural change is achieved, understanding and addressing the pathways through which neighborhood stress affects development remains essential for fostering resilience and promoting equity in child outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions:

FAQs

Q1. How does neighborhood stress impact a child’s cognitive development? Neighborhood stress can markedly affect a child’s cognitive development by altering brain structure and function. Children from disadvantaged neighborhoods may exhibit blunted responses to rewards and losses, reduced gray matter in vital brain regions, and heightened amygdala reactivity to fear and threat. These neurobiological changes can lead to poor cognitive outcomes and challenges in learning and behavior.

Q2. What are some signs of poor cognitive development in children exposed to neighborhood stress? Children exposed to neighborhood stress may show difficulties with executive functions such as inhibition, working memory, and planning abilities. They might also exhibit altered developmental patterns that persist even after controlling for socioeconomic factors. Additionally, these children may demonstrate problems with verbal comprehension and overall intelligence compared to those from less disadvantaged areas.

Q3. Can parenting help mitigate the effects of neighborhood disadvantage on children? Yes, nurturing parenting can remarkably buffer the negative impacts of neighborhood disadvantage on children’s cognitive development. High-quality caregiving can reduce stress, prevent stress hormone release, and modulate emotional reactivity in children. Research shows that parental nurturance can protect children from the adverse effects of community violence exposure and reduce amygdala reactivity to threats.

Q4. How do household conditions contribute to cognitive stress in children? Household chaos, characterized by disorganization, lack of routines, and unpredictability, can independently affect cognitive development beyond socioeconomic factors. Environmental noise, particularly from transportation sources, can also impair reading ability and increase behavioral difficulties. These factors create additional cognitive stressors that can compound the effects of neighborhood disadvantage.

Q5. Are there any interventions that can improve cognitive outcomes for children in disadvantaged neighborhoods? Yes, early childhood interventions have shown promising results in improving cognitive outcomes. Programs like Research-based Developmentally Informed (REDI) and Promoting Alternative Thinking Skills (PATHS) have demonstrated improvements in vocabulary, emergent literacy, and executive functions. Even brief mindfulness training can produce measurable improvements in cognitive abilities, especially for children initially showing poor executive functions.

References:

[1] – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412021005869

[2] – https://www.cdc.gov/child-abuse-neglect/communication-resources/efc-promoting-positive-community-norms.pdf

[3] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7986388/

[4] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3387518/

[5] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4713249/

[6] – https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2024/02/violent-neighborhoods-brain-development

[7] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3831447/

[8] – https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/20438087221132501

[9] – https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/05/250505171008.htm

[10] – https://www.binghamton.edu/news/story/5536/study-neighborhood-stress-may-impact-kids-brains-and-increase-depression-risk

[11] – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2451902222001288

[12] – https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/development-and-psychopathology/article/exploring-longitudinal-associations-between-neighborhood-disadvantage-and-cortisol-levels-in-early-childhood/A029CF113630382B3A3051C7A7D6AE88

[13] – https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/human-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00277/full

[14] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10714216/

[15] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8408896/

[16] – https://biolmoodanxietydisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2045-5380-4-12

[17] – https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/2778480

[18] – https://www.yalemedicine.org/conditions/how-parental-depression-affects-child

[19] – https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.

2023.1151897/full

[20] – https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-020-08587-8

[21] – https://bmcpsychology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40359-021-00651-1

[22] – https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/the-effect-of-environmental-noise-on-children

[23] – https://news.illinois.edu/poor-diet-household-chaos-may-impair-young-childrens-cognitive-skills/

[24] – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29720785/

[25] – https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/1035027

[26] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11197980/

[27] – https://acamh.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/camh.12764?af=R

[28] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6051751/

[29] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3159917/

[30] – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37590215/

[31] – https://www.diversitydatakids.org/child-opportunity-index

[32] – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2667174325000874