The Truth About Physician Financial Myths: What Most Doctors Get Wrong

Check out our extensive video library (see channel for our latest videos)

Introduction

Physician financial myths persist despite the extensive education doctors receive. According to recent research by AMA Insurance, fewer than 5% of physicians consider themselves “very knowledgeable” about personal finances and retirement planning . While doctors earn impressive incomes—averaging $339,000 annually with specialists making around $368,000 —their financial literacy often fails to match their medical expertise.

The disconnect between income and wealth becomes apparent when examining physicians’ actual financial standing. Surprisingly, 28% of doctors have a net worth under $500,000, and nearly half possess less than one million dollars . This wealth gap exists partly because medical school graduates typically begin their careers with approximately $200,000 in educational debt . Furthermore, every dollar spent during medical school ultimately costs $1.50-$2.00 when finally repaid . Unfortunately, as noted in physician forums, doctors commonly make financial mistakes that undermine their long-term security . This reality contradicts the common perception that physicians automatically achieve financial success through their careers.

This article examines the most pervasive physician financial myths, explores their implications, and provides evidence-based strategies to help doctors develop sound financial practices. From understanding the true relationship between income and wealth to recognizing the importance of early financial planning, these insights aim to address the financial pitfalls many physicians face throughout their careers.

Myth 1: High income means financial security

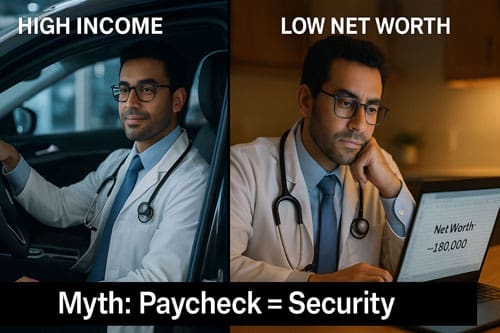

Many medical professionals fall prey to one of the most common physician financial myths: equating their substantial income with financial security. Across the United States, physicians earn impressive salaries—averaging $350,000 annually [1]—yet this figure masks a more complex financial reality.

Why income doesn’t equal wealth

The distinction between income and wealth remains critically important, especially for doctors. Although physicians rank among America’s highest earners, their substantial paychecks often fail to translate into proportional wealth. This disconnect stems from several factors unique to the medical profession.

First, the delayed earning trajectory significantly impacts wealth accumulation. Medical professionals typically begin their careers later than their counterparts in other fields, with most physicians starting independent practice around age 31 [2]. Consequently, doctors face a shortened timeline for saving and investing compared to professionals who enter the workforce earlier.

Second, the burden of educational debt presents a major obstacle. Medical school graduates typically emerge with approximately $203,000 in student loans [2], creating a substantial negative net worth at career start. Indeed, some physician households report negative net worth exceeding -$670,000 when combining educational debts [3].

Third, lifestyle inflation frequently erodes potential wealth building. As Joel Greenwald, a physician wealth management advisor, notes, many doctors increase spending dramatically once their income rises, particularly on housing and automobiles [1]. Moreover, approximately 7% of physicians admit to living above their means [4], further diminishing their capacity to build wealth.

The role of net worth in physician finance

Net worth—calculated as assets minus liabilities—provides a more accurate measure of financial health than income alone. This metric reveals how effectively physicians translate their earnings into lasting wealth.

A concerning reality emerges when examining physician net worth data. Among doctors in their 60s, 25% have net worth below $1 million, and 11-12% have less than $500,000 [5]—despite decades of substantial earnings. Even more troubling, 18% of family medicine physicians and 17% of internal medicine physicians report net worth under $500,000 [1].

Additionally, gender disparities persist in wealth accumulation. Male physicians are twice as likely as their female colleagues to achieve net worth exceeding $5 million (10% versus 5%) [4]. Overall, merely 56% of physicians report a net worth of at least $1 million [1]—far lower than might be expected given their income levels.

For physicians aiming to assess their financial health, several benchmarks exist. One formula suggests that a doctor’s expected net worth should equal their salary multiplied by years since training completion, then multiplied by 0.25 [6]. By this measure, an orthopedist earning $500,000 annually five years post-residency should have accumulated between $313,000 and $1.25 million [6].

Nevertheless, certain physicians build exceptional wealth through entrepreneurship or disciplined investing. Some doctor-entrepreneurs develop multi-physician practices that significantly enhance their financial position, with a small percentage (15-22%) eventually achieving net worth exceeding $5 million [5].

Ultimately, physicians must recognize that financial security depends not on their income but on their ability to convert that income into lasting assets. Without intentional wealth-building strategies, even the most highly compensated doctors risk reaching retirement with inadequate resources.

Myth 2: You can delay financial planning until later

The delayed start of a physician’s earning potential creates one of the most dangerous physician financial myths: that financial planning can wait until later in their career. In reality, time plays a crucial role in building wealth, regardless of income level.

The cost of waiting to invest

Many physicians don’t begin investing until age 30-35—approximately a decade later than professionals in other fields [7]. This delayed timeline creates a substantial financial disadvantage that extends far beyond the training years. Every year of postponed investment represents a lost opportunity for compound growth that cannot be reclaimed, even with a physician’s higher eventual income.

The mathematics of compound interest clearly illustrates this problem. A physician who waits until after residency to begin investing might miss 5-10 critical years of growth [8]. In practical terms, two professionals—one starting at age 22 and another at age 32—will see dramatically different outcomes despite identical contribution amounts [9].

This delay is often justified through seemingly logical reasoning: “I’ll focus on paying off my student loans first, then start investing” [8]. However, this approach overlooks an important reality: physicians who earn substantial incomes can often manage both debt repayment and investment simultaneously [8]. The opportunity cost of waiting becomes apparent only years later, when physicians realize they must save significantly more to compensate for lost time.

Additionally, physicians face unique pressures that exacerbate the problem of delayed investing:

-

High educational debt (exceeding $200,000 for the average medical graduate) [10]

-

Extended training periods that postpone peak earning years

-

Expectations for rapid lifestyle improvements after training

-

Limited financial education during medical training [10]

How early habits shape long-term outcomes

The financial habits established during residency and early practice years profoundly influence a physician’s long-term financial health. Physicians who develop disciplined financial practices early gain a distinct advantage over colleagues who postpone these decisions.

An AMA Insurance study found that over half of young physicians feel they don’t spend enough time on financial planning, with nearly 9 in 10 feeling inadequately protected against disability [11]. This lack of early planning creates vulnerabilities that compound over time.

The most successful physician investors establish several critical habits from the outset. First, they maximize workplace retirement plans and employer matches rather than deferring these contributions [12]. Second, they develop automated savings systems that prioritize paying themselves first [7]. Third, they carefully balance debt repayment with strategic investing, recognizing that both objectives can be pursued concurrently [8].

Most notably, these early habits shield physicians from the pressure to “catch up” later through higher-risk investments or extended working years [7]. Instead of focusing exclusively on student loan repayment, financially savvy doctors recognize that even modest early investments—perhaps 10-15% of income—create a foundation that grows exponentially over decades [1].

For physicians who feel they’ve started late, perspective matters. Even a physician beginning in their 40s still has 15-20 years to build substantial wealth [1]. Nevertheless, the financial advantage clearly belongs to those who reject the myth that financial planning can wait until after training.

Myth 3: Doctors don’t need financial advisors

Among the prevalent physician financial myths lies the misconception that doctors possess sufficient expertise to manage their investments without professional guidance. This belief stems partly from physicians’ intelligence and self-reliance—traits essential for medical practice yet potentially detrimental to financial outcomes.

The risks of DIY investing

Physician-directed investing introduces several distinctive challenges. First, the demands of clinical practice leave minimal time for thorough financial analysis. Most doctors work 50-60 hours weekly on patient care alone, creating a substantial time deficit for investment research. Second, medical training provides virtually no foundation in finance, leading to knowledge gaps in critical areas like asset allocation and tax efficiency.

Perhaps most importantly, physicians face the same emotional biases that affect all investors. Research demonstrates that self-directed investors typically underperform market benchmarks by 1.5% to 4% annually due to behavioral errors. For physicians specifically, these emotional decisions often manifest as excessive risk-taking or panic selling during market volatility.

How to choose the right advisor

Finding appropriate financial guidance requires physicians to evaluate several key factors:

-

Credentials and education – Advisors should hold relevant designations such as CFP (Certified Financial Planner), CFA (Chartered Financial Analyst), or ChFC (Chartered Financial Consultant), indicating specialized training beyond basic licensing requirements

-

Experience with physician clients – Advisors familiar with medical careers understand the unique challenges of delayed earning potential, student debt management, and practice-specific concerns

-

Fiduciary obligation – The advisor must legally commit to putting client interests ahead of their own, particularly important given the complex products often marketed to high-earning professionals

Physicians should generally avoid advisors who exclusively represent specific insurance companies or limit investment options to proprietary products. Likewise, advisors unwilling to clearly disclose all compensation methods warrant caution.

Fee-only vs commission-based advisors

The compensation structure fundamentally shapes advisor incentives and recommendations. Fee-only advisors charge directly for services—typically 0.75% to 1.5% of assets managed annually or hourly rates ranging from $200-$400. This model minimizes conflicts of interest since compensation doesn’t depend on specific product recommendations.

In contrast, commission-based advisors earn through product sales, potentially creating incentives to recommend higher-commission options regardless of suitability. A middle ground exists with fee-based advisors who charge management fees alongside certain commissions.

For most physicians, fee-only advisors provide the clearest alignment of interests, though their services may appear more expensive initially compared to “free” commission-based advice. This transparency allows physicians to accurately evaluate what they receive for the costs incurred.

Ultimately, while medical expertise doesn’t automatically translate to financial acumen, neither does hiring any advisor guarantee optimal results. The ideal approach combines selective professional guidance with ongoing financial education, addressing this pervasive myth in physician finance with balanced perspective.

Myth 4: Spending equals success

The spending habits of newly practicing physicians represent yet another physician financial myth: the belief that higher spending reflects greater success. After years of delayed gratification during training, many doctors succumb to rapid spending increases that undermine their long-term financial health.

Lifestyle inflation and its hidden cost

Lifestyle inflation occurs as physicians transition from residency to practice and dramatically increase their spending. Following years of modest living, doctors suddenly find themselves with an additional $40,000-$100,000 annually and often respond by upgrading homes, vehicles, and overall lifestyle [2]. This pattern creates a dangerous financial trajectory.

In fact, the mathematical impact of increased spending extends beyond immediate budgets. Consider a physician who increases annual spending from $120,000 to $200,000. This decision doesn’t merely reduce savings—it fundamentally alters retirement planning. To maintain this elevated lifestyle in retirement, their required nest egg jumps from $3 million to $5 million, potentially extending their working years by 17 to 42 additional years [13].

Research shows that spending patterns established during residency have lasting effects throughout a physician’s career. Doctors trained in high-spending regions continue these expensive practice patterns even if they relocate, with up to 7% difference in patient expenditures between low and high-spending training regions [14].

Why appearances can be deceiving

The pressure to “keep up with the Joneses” remains particularly intense in medical communities. Many physicians appear financially successful based on external markers—luxury vehicles, expansive homes, exotic vacations—yet these visible signals often mask concerning financial realities.

Our image-driven culture incorrectly equates appearance with health and success. As one researcher notes, “looking good, through being healthy, sells” [15]. Similarly, financial appearances frequently mislead. A colleague driving an expensive car might simultaneously carry $30,000 in credit card debt [16].

How to align spending with values

Forward-thinking physicians adopt an inverse approach to budgeting. Rather than allowing lifestyle inflation to determine savings, they first establish savings targets based on retirement goals, then build a lifestyle with what remains [17].

One effective method involves saving a fixed percentage of income. For instance, a physician making $200,000 annually might target saving 30%—$60,000—regardless of income increases [2]. This approach permits lifestyle improvements without compromising long-term security.

The key distinction lies in spending with intention versus habit. For expenses to provide genuine satisfaction, they should align with a physician’s core values rather than external expectations. Identifying what truly creates happiness—whether travel, time with family, or intellectual pursuits—allows doctors to direct resources toward meaningful experiences [16].

Myth 5: Retirement planning can wait

One of the costliest physician financial myths concerns retirement timing—the mistaken belief that physicians can postpone retirement planning until after establishing their practice. This misconception proves particularly damaging given the mathematics of long-term investing.

Late start due to long training

Unlike other professionals, physicians typically delay significant earning and saving until their 30s. Most doctors remain unable to save during medical school, residency, and fellowships [5]. This delayed timeline creates an immediate disadvantage in wealth accumulation. With career starts frequently 8-10 years behind peers in other professions, physicians face a compressed timeframe to build retirement assets while simultaneously managing student debt, home purchases, and family formation.

Why compound interest favors early savers

The mathematics of compound growth overwhelmingly favor those who start early—even with smaller contributions. Consider a physician who begins investing $50,000 annually at age 30. By age 57, assuming 8% returns, this doctor would accumulate $4,716,941 [3]. Conversely, delaying contributions reduces this sum dramatically.

The “eighth wonder of the world”—compound interest—works most powerfully in later years. After 25% of a 40-year investment timeline, an investor holds merely 4% of their eventual wealth; at the halfway mark, only 16% [6]. Hence, physicians who postpone retirement planning sacrifice their most valuable asset: time.

Retirement vehicles physicians should know

Given their unique circumstances, physicians should familiarize themselves with specialized retirement options:

Solo 401(k)s offer independent contractor physicians greater flexibility than SEP IRAs, with 2025 contribution limits reaching $70,000 ($77,500 for those over 50) [4]. These plans permit contributions through employee deferrals, profit-sharing, and after-tax additions.

Cash balance plans allow physicians to contribute substantially more—potentially exceeding $200,000 annually—while reducing taxable income [4]. These defined-benefit approaches work effectively for physicians around age 45 or older [4].

Additionally, Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) provide triple tax advantages: pre-tax contributions, tax-deferred growth, and tax-free withdrawals for medical expenses [18].

Physicians must reconcile the reality that while starting earlier remains optimal, beginning now—at any career stage—offers better outcomes than further delay. As financial expert William Zelenik notes, “There’s still hope, but the sooner, the better. Don’t wait to start saving until it’s too late—time can be a great friend or a great enemy” [19].

Conclusion

Throughout their careers, physicians face financial challenges that often contradict common assumptions about their wealth. Despite earning substantial incomes, many doctors struggle to build proportional net worth due to delayed career starts, educational debt burdens, and lifestyle inflation. These realities underscore why physicians must recognize the distinction between income and financial security.

Time remains the most valuable asset in wealth accumulation. Physicians who postpone investment during training years sacrifice irreplaceable compound growth opportunities that even their higher eventual incomes cannot overcome. Early financial habits established during residency shape long-term outcomes far more powerfully than most doctors realize.

While medical expertise develops through rigorous training, financial acumen requires different skills entirely. Doctors who attempt to manage investments independently often face constraints of time, knowledge gaps, and emotional biases that undermine returns. Fee-only advisors with fiduciary obligations generally offer the most aligned guidance for physicians’ unique circumstances.

External appearances frequently mislead within medical communities. Colleagues who display traditional symbols of wealth—luxury vehicles and expansive homes—may simultaneously carry substantial debt burdens. Thoughtful physicians instead align spending with personal values, establishing savings targets first, then building lifestyle choices with remaining resources.

The mathematics of compound interest creates clear advantages for early investors. Each year of postponed retirement planning dramatically reduces potential wealth accumulation. Physicians must therefore familiarize themselves with specialized retirement vehicles like Solo 401(k)s, cash balance plans, and Health Savings Accounts that accommodate their compressed timeline for wealth building.

Financial literacy thus serves as an essential professional skill for physicians. Those who reject these prevalent myths position themselves to convert their hard-earned incomes into lasting wealth. After all, financial wellness ultimately enables physicians to focus on their primary mission—providing exceptional patient care—without the burden of economic insecurity.

Key Takeaways

Despite earning substantial incomes, many physicians struggle with financial security due to common misconceptions about wealth building. Here are the critical insights every doctor should understand:

• High income doesn’t guarantee wealth – 28% of doctors have net worth under $500,000 despite averaging $339,000 annually, proving income and wealth are different metrics.

• Delaying financial planning costs exponentially – Physicians who wait until after residency to invest miss 5-10 critical years of compound growth that cannot be recovered.

• Professional guidance prevents costly mistakes – Self-directed physician investors typically underperform market benchmarks by 1.5-4% annually due to time constraints and emotional biases.

• Lifestyle inflation destroys wealth potential – Increasing spending from $120,000 to $200,000 annually requires an additional $2 million in retirement savings to maintain that lifestyle.

• Time is more valuable than income amount – Starting retirement contributions at age 30 versus 40 can result in hundreds of thousands more in accumulated wealth, even with identical contribution amounts.

The key to physician financial success lies in recognizing that medical expertise doesn’t automatically translate to financial acumen, and that early, disciplined financial habits matter more than high earnings alone.

Frequently Asked Questions:

FAQs

Q1. Do high salaries guarantee financial security for physicians? No, high salaries don’t automatically translate to financial security. Despite earning substantial incomes, many physicians struggle to build proportional wealth due to factors like delayed career starts, educational debt, and lifestyle inflation. It’s important to focus on building net worth rather than just relying on income.

Q2. When should physicians start financial planning? Physicians should start financial planning as early as possible, ideally during residency. Delaying financial planning and investing can result in significant opportunity costs due to missed compound growth. Even small contributions early in one’s career can have a substantial impact on long-term wealth accumulation.

Q3. Do doctors need financial advisors? While not mandatory, many physicians can benefit from working with a financial advisor. The complexities of physician finances, combined with time constraints and potential knowledge gaps in financial matters, make professional guidance valuable. It’s important to choose a fee-only advisor with a fiduciary obligation to act in your best interests.

Q4. How does increased spending affect a physician’s long-term financial health? Increased spending, often referred to as lifestyle inflation, can significantly impact a physician’s long-term financial health. For example, increasing annual spending from $120,000 to $200,000 not only reduces immediate savings but also requires a much larger retirement nest egg, potentially extending working years by 17 to 42 years.

Q5. What retirement planning options are available for physicians? Physicians have several specialized retirement planning options available to them. These include Solo 401(k)s for independent contractors, cash balance plans for higher contributions, and Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) which offer triple tax advantages. It’s crucial for physicians to familiarize themselves with these options to maximize their retirement savings potential.

References:

[1] – https://moneywisedoctor.com/tax-efficient-investing-for-doctors-catch-up/

[2] – https://www.whitecoatinvestor.com/lifestyle-inflation-and-its-impact/

[3] – https://www.healio.com/news/hematology-oncology/20240911/start-early-to-leverage-the-power-of-compound-interest

[4] – https://www.coreclinicalpartners.com/best-retirement-plans-for-physicians-how-doctors-maximize-wealth/

[5] – https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/3-cornerstones-young-physicians-need-for-a-solid-financial-foundation

[6] – https://www.whitecoatinvestor.com/the-end-matters-most-compound-interest-at-its-finest/

[7] – https://curicapital.com/news-and-insights/six-common-financial-concerns-physicians

[8] – https://www.myinvestmentinsight.com/blog/financial-planning-for-doctors/

[9] – https://www.reddit.com/r/whitecoatinvestor/comments/1ocyp31/

the_impact_of_delayed_investment_contributions_as/

[10] – https://myfinancialcoach.com/why-young-physicians-must-prioritize-financial-planning-early-in-their-careers/

[11] – https://www.ama-assn.org/medical-residents/medical-residency-personal-finance/5-financial-planning-tips-every-young

[12] – https://doctordisability.com/6-investing-mistakes-doctors-make-too-often/

[13] – https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/the-brutal-effect-of-lifestyle-inflation-on-your-finances

[14] – https://www.ajmc.com/view/residency-has-lasting-effect-on-spending-habits-of-doctors

[15] – https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6177750_A_Picture_of_

Health_unmasking_the_role_of_appearance_in_health

[16] – https://www.laurelroad.com/healthcare-banking/5-habits-to-help-doctors-avoid-lifestyle-inflation/

[17] – https://www.physicianonfire.com/physician-lifestyle-inflation/

[18] – https://wealthkeel.com/blog/retirement-savings-accounts-for-physicians/

[19] – https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/career-development/retirement-savings-strategies-physicians-start-late