Pediatric Obesity: Should We Prescribe GLP-1 Agonists for Adolescents?

Abstract

Pediatric obesity has become a global public health crisis, affecting roughly 20 percent of children and adolescents worldwide. While lifestyle modifications such as dietary changes, increased physical activity, and behavioral therapy remain the foundation of treatment, their long-term effectiveness is often limited, especially in cases of severe obesity. The recent approval of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) for adolescents offers a new pharmacological approach that may help address this growing challenge.

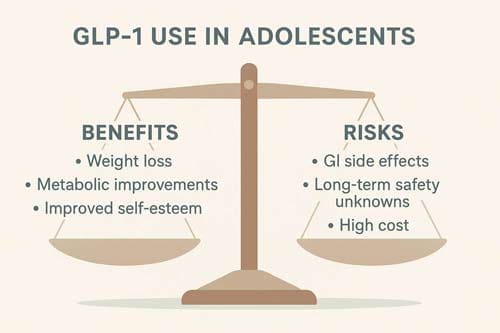

This review critically examines the current evidence supporting the use of GLP-1 RAs, including their efficacy, safety, cost-effectiveness, and ethical implications in the pediatric population. Meta-analyses of clinical trials show that GLP-1 RAs, particularly semaglutide, lead to moderate but clinically meaningful reductions in body weight among adolescents with obesity. These outcomes are promising and represent a vital step forward in medical obesity treatment for youth.

However, several concerns remain. Long-term safety data are still limited, especially regarding potential impacts on mental health and metabolic development during adolescence. High drug costs may limit accessibility and widen existing health disparities, particularly among underserved populations. Ethical concerns also arise when prescribing chronic pharmacotherapy to a developing population, underscoring the importance of cautious, individualized use.

Given these complexities, the use of GLP-1 RAs in adolescents should be reserved for those with severe obesity or those who have not responded adequately to lifestyle interventions. Their prescription should follow evidence-based clinical guidelines, with close monitoring for both therapeutic response and adverse effects. Multidisciplinary care teams—including pediatricians, endocrinologists, dietitians, and mental health professionals—are essential to ensure comprehensive and safe management.

Looking ahead, further research is needed to determine long-term outcomes, refine patient selection criteria, and develop strategies to improve affordability and access. As part of a broader, integrated approach to pediatric obesity care, GLP-1 RAs may offer important benefits for carefully selected adolescents, provided their use is supported by rigorous clinical oversight.

Keywords: pediatric obesity, GLP-1 receptor agonists, semaglutide, adolescent weight management, pharmacotherapy, long-term safety, health equity, obesity treatment

Introduction

The global pediatric obesity epidemic represents one of the most pressing public health challenges of the 21st century. In 2021, an estimated 15.1 million children and young adolescents (aged 5-14 years) and 21.4 million older adolescents (aged 15-24 years) had overweight or obesity in the USA [1]. The prevalence of childhood obesity in the United States has more than tripled over the last four decades from 5 percent in 1978 to 18.5 percent in 2016 [2]. This alarming trend extends globally, with 1 of 5 children or adolescents experiencing excess weight [3] across diverse populations.

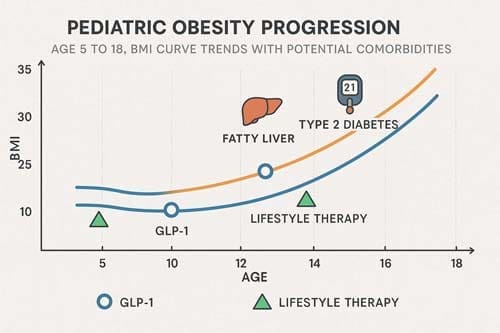

The implications of childhood obesity extend far beyond aesthetic concerns. Obesity in children may lead to hypertension, coronary disease, and a greater incidence of diabetes complications and metabolic syndrome [4]. Moreover, adults who were obese as children have increased mortality independent of adult weight [5], underscoring the critical importance of early intervention.

Traditional approaches to pediatric obesity management have centered on lifestyle interventions incorporating dietary modifications, physical activity, and behavioral counseling. While these interventions demonstrate efficacy in controlled settings, their real-world application faces major challenges. In clinical practice, the degree of weight loss with lifestyle intervention is only moderate, and the success rate 2 years after onset of an intervention is low (<10% with a decrease in BMI SD score of <0.25) [6].

The emergence of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) as effective obesity treatments in adults has prompted investigation of their potential in pediatric populations. Semaglutide was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for weight management in adolescents aged 12 years and above in December 2022 [7], marking a remarkable milestone in pediatric obesity pharmacotherapy.

This analytical review examines the complex question of whether GLP-1 RAs should be prescribed for adolescents with obesity. We will explore the current evidence base, analyze benefits and risks, examine cost-effectiveness considerations, and discuss the ethical implications of introducing these medications into pediatric practice. The analysis aims to provide healthcare providers, policymakers, and stakeholders with a comprehensive understanding of this evolving therapeutic landscape.

Literature Review and Current Evidence

Efficacy of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Adolescents

The evidence base for GLP-1 RA efficacy in adolescent obesity has grown substantially in recent years. Meta-analyses indicate that GLP-1 receptor agonists are safe and effective in modestly reducing weight, BMI, glycated hemoglobin A1c, and systolic blood pressure in children and adolescents with obesity in a clinical setting, albeit with increased rates of nausea [8] [9].

The landmark STEP TEENS trial demonstrated the efficacy of semaglutide in adolescents with obesity. Among adolescents with obesity, once-weekly treatment with a 2.4-mg dose of semaglutide plus lifestyle intervention resulted in a greater reduction in BMI than lifestyle intervention alone [10]. More specifically, a recently published, randomized, placebo-controlled trial found a greater reduction in BMI z-score (- 0.22 SDs) in adolescents receiving liraglutide compared with placebo [11] [12].

Recent comprehensive meta-analyses have provided more detailed insights into the comparative effectiveness of different GLP-1 RAs. Meta-analysis demonstrated that GLP-1 RAs had a superior anti-obesity effect compared to placebo or lifestyle modification in obese or overweight non-diabetic adolescents, particularly semaglutide, which had a more pronounced anti-obesity effect than liraglutide and exenatide [13].

The clinical significance of these weight reductions extends beyond mere BMI improvements. Semaglutide was highly effective in reducing BMI category. While on treatment, most trial participants’ BMI improved by at least one category, and >40% reached a category below the obesity threshold [14]. This represents a clinically meaningful outcome that could substantially impact long-term health trajectories.

Safety Profile and Adverse Events

Safety considerations are paramount when evaluating any medication for pediatric use. The safety profile of GLP-1 RAs in adolescents largely mirrors that observed in adult populations, with gastrointestinal adverse events being the most common concern.

The most common symptoms associated with the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists are gastrointestinal symptoms, mainly nausea [15]. Other common adverse effects include injection site reactions, headache, and nasopharyngitis, but these effects do not usually result in discontinuation of the drug [16]. This meta-analysis indicates that GLP-1 receptor agonists are safe and effective in modestly reducing weight, BMI, glycated hemoglobin A1c, and systolic blood pressure in children and adolescents with obesity in a clinical setting, albeit with increased rates of nausea [17].

Recent comprehensive safety analyses have provided additional reassurance. GLP-1 RA reduced BMI, body weight, and waist circumference. Although lipid profiles, HbA1c, and FBG were unaffected, GLP-1 RA was linked to a slight reduction in SBP and an increase in HR, with no notable effect on DBP. Adverse effects, primarily nausea and vomiting, were more common in the intervention group, although trial withdrawal rates remained low [18].

However, emerging concerns about mental health impacts warrant careful consideration. Utilizing the Bradford Hill criteria reveals insufficient evidence for a direct causal link between GLP-1 agonists and STB. Yet, the indirect effects related to the metabolic and psychological disturbances associated with rapid weight loss call for a cautious approach [19]. This highlights the importance of comprehensive mental health screening and monitoring during treatment.

Mechanism of Action and Physiological Effects

Understanding the mechanism of action of GLP-1 RAs provides insight into their therapeutic effects and potential applications in pediatric obesity. GLP-1RA’s efficacy extends beyond glycemic control to include weight loss mechanisms such as delayed gastric emptying (gastroparesis), and appetite suppression [20].

The physiological effects of GLP-1 RAs are multifaceted. GLP-1 is an incretin hormone that is produced and secreted by intestinal L-cells and in the central nervous system by neurons in the brainstem. GLP-1 stimulates postprandial insulin secretion and reduces glucagon production from pancreatic cells. It leads to a delay of gastric emptying, improved glycemic control, and a reduction of feelings of hunger and food craving [21].

Research has also revealed potential neurological benefits. Several anti-hyperglycemic agents as metformin and GLP-1RAs might not only lead to a weight reduction in patients living with obesity, T2D and mood disorders but also have a beneficial effect on depressive symptoms and cognitive functions. There is evidence from in vitro and in vivo studies that GLP-1R activation might have neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties by reducing the inflammatory response. GLP-1 might exert a modulatory effect on the release of neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine and on the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [22].

Comparative Effectiveness with Other Interventions

To fully understand the role of GLP-1 RAs in pediatric obesity management, it is essential to compare their effectiveness with existing interventions. GLP-1R agonists appear to perform favorably compared with other approved pharmacological agents for pediatric obesity. However, heterogeneity in weight loss response, cost, side effects, and need for injections may limit their use in many pediatric patients [23].

The evidence suggests that GLP-1 RAs may be particularly valuable when lifestyle interventions alone prove insufficient. GLP-1RAs may offer a promising adjunct therapy for pediatric obesity, particularly in cases where lifestyle interventions alone are insufficient [24]. This positioning is crucial, as it frames GLP-1 RAs not as first-line treatments but as important tools in a comprehensive management strategy.

Recent comparative analyses have provided additional context. Compared with controls, GLP-1 agonist therapy reduced HbA1c by -0.30% with a larger effect in children with (pre-)diabetes (-0.72%) than in children with obesity (-0.08%). Conversely, GLP-1 agonist therapy reduced body weight more in children with obesity (-2.74 kg) than in children with T2DM (-0.97 kg) [25].

Analysis of Benefits and Risks

Clinical Benefits

The clinical benefits of GLP-1 RAs in adolescent obesity extend beyond simple weight reduction. The comprehensive metabolic effects offer multiple potential advantages for young patients struggling with obesity-related comorbidities.

Weight loss effectiveness represents the primary benefit. Semaglutide, as a once weekly subcutaneous injection for weight management, effectively reduces body mass index (BMI) while improving hyperglycemia, elevated alanine aminotransferase levels, hyperlipidemia, and quality of life in youth with obesity [26]. The magnitude of weight loss achieved with GLP-1 RAs often exceeds that seen with lifestyle interventions alone, potentially providing hope for adolescents who have struggled with traditional approaches.

Cardiometabolic improvements constitute another benefit. Within this specific population, GLP-1 RAs exhibit major reductions in BW, BMI, WC, and SBP. The analyses of lipid profiles, DBP, HbA1c, and FBG showed no remarkable changes [27]. These improvements in cardiovascular risk factors during adolescence may have profound implications for long-term health outcomes.

The psychological benefits of successful weight management should not be underestimated. Adolescents with obesity often experience increasing psychosocial challenges, including bullying, social isolation, and reduced self-esteem. Successful weight management interventions can improve quality of life and mental health outcomes.

Safety Concerns and Risks

Despite their efficacy, GLP-1 RAs present several safety concerns that must be carefully evaluated in adolescent populations. The developing physiology of adolescents and the long-term nature of obesity treatment raise unique considerations.

Gastrointestinal adverse events represent the most common safety concern. Several case reports have linked the use of these drugs, mainly exenatide, with the occurrence of acute kidney injury, primarily through hemodynamic derangement due to nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea [28]. While these events are generally manageable, they can notably impact treatment adherence and quality of life.

Mental health considerations have emerged as a key concern. While GLP-1 agonists can contribute to substantial health improvements, they also introduce biological and psychological stressors. Disruptions in homeostasis from quick weight reduction can elevate cortisol and norepinephrine levels, heightening the risk for, or exacerbation of STB. Psychological factors, including unfulfilled expectations and identity changes after marked weight loss, compound these risks [29].

The need for ongoing monitoring and support presents both practical and safety considerations. In the context of clinical practice, it may be important to assess for symptoms of eating disorders/disordered eating behaviors, mood instability, and general psychosocial functioning as well as quality of life, social support, health behaviors, and readiness to change prior to the initiation of and throughout the course of GLP-1 treatment [30].

Long-term safety data remain limited. As of this review, only one large randomized clinical trial of semaglutide in youth has been completed, with a follow-up duration of 68 weeks. Thus, long-term data on the safety in adolescents is limited, particularly regarding the risks of cholelithiasis, pancreatitis, suicidal ideation, and disordered eating [31].

Special Populations and Considerations

Certain subgroups of adolescents may derive particular benefit from GLP-1 RA therapy or require special consideration. A recent case series underscored the benefits of therapy with liraglutide, a short-acting GLP-1 analogue, in rare genetic cases of early-onset obesity [32]. This suggests that GLP-1 RAs may be particularly valuable for adolescents with genetic forms of obesity who have limited response to lifestyle interventions.

The timing of intervention may also be key. In particular, children aged 5-12 years and children with overweight rather than obesity profit from lifestyle interventions [33]. This suggests that GLP-1 RAs may be most appropriate for adolescents with established obesity who have not responded to comprehensive lifestyle interventions.

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

Economic Burden of Pediatric Obesity

The economic impact of pediatric obesity extends far beyond immediate healthcare costs. Over the past several decades, the overweight and obesity epidemic in the USA has resulted in a notable health and economic burden. Understanding current trends and future trajectories at both national and state levels is crucial for assessing the success of existing interventions and informing future health policy changes [34].

The long-term costs associated with obesity-related comorbidities justify consideration of more expensive interventions if they prove effective. Adults who were obese as children have increased mortality independent of adult weight. Thus, prevention programs for children and adolescents will have long-term benefits [35].

Cost of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists

The high cost of GLP-1 RAs represents a barrier to widespread adoption. However, this effectiveness comes with an exorbitant cost, with the retail price of these medications over $1000 per month [36] [37]. This cost burden extends beyond medication expenses to include monitoring, administration, and management of adverse events.

Cost-effectiveness analyses in adult populations have shown mixed results. Among the 4 GLP-1RAs, Semaglutide was the most cost-effective obesity medication [38] [39]. However, Despite glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists GLP1 higher efficacy, higher cost makes them not cost-effective [40] in many healthcare systems.

The pediatric population presents unique cost-effectiveness considerations. Due to the cost of semaglutide, particularly in the United States, limited cost effectiveness analyses have demonstrated unfavorable incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for semaglutide relative to phentermine-topiramate as an alternative antiobesity medication in adolescents [41].

Long-Term Economic Considerations

The long-term economic implications of effective obesity treatment in adolescence may justify the high upfront costs. The findings revealed a crucial insight, for some GLP-1 s like Saxenda and Wegovy, the high cost of ongoing use surpasses the cost of RYGB in less than a year and sleeve gastrectomy within nine months [42]. This comparison with bariatric surgery costs provides important context for economic evaluations.

However, the potential for long-term cost savings through prevention of obesity-related complications must be considered. Pronounced economic benefits of GLP-1RA therapy among those with prior CVDs or CKDs support rational treatment decisions and optimal healthcare resource allocation for these patients [43].

Access and Equity Considerations

The high cost of GLP-1 RAs raises major concerns about health equity and access. Insurance coverage for antiobesity medications varies. Patients perceive the discontinuation of anti-obesity medication coverage as stigmatizing and unjust, leading to feelings of hopelessness and fear. With more insurance companies denying coverage for these costly medications more information is needed to identify best ways to address the loss of coverage with patients [44] [45].

The potential for creating or exacerbating health disparities must be carefully considered. Finally, we discuss health inequities in obesity, the dangers of perpetuating these inequities if GLP-1RA access remains biased, and the opportunities for improvement [46].

Ethical Considerations

Autonomy and Informed Consent

The use of GLP-1 RAs in adolescents raises complex questions about autonomy and informed consent. Adolescents may not fully understand the long-term implications of starting these medications, particularly regarding potential lifelong use and associated costs.

The developmental stage of adolescence complicates decision-making processes. Adolescents may experience significant pressure from parents, peers, and society to lose weight, potentially compromising their ability to make truly autonomous decisions about treatment.

Beneficence and Non-Maleficence

The principle of beneficence requires that the benefits of GLP-1 RA therapy outweigh the risks. Semaglutide represents an important advance in the pediatric obesity management, with clear short-term reductions in BMI and improvement in metabolic parameters. However, its long-term safety and efficacy for youth with obesity remain to be demonstrated [47].

The principle of non-maleficence (“do no harm”) must consider both the risks of treatment and the risks of untreated obesity. Childhood obesity affects multiple organs in the body and is associated with both marked morbidity and ultimately premature mortality. The prevalence of complications associated with obesity, including dyslipidaemia, hypertension, fatty liver disease and psychosocial complications are becoming increasingly prevalent within the paediatric populations.

Justice and Fairness

The principle of justice requires fair distribution of benefits and burdens. The high cost of GLP-1 RAs may create a system where effective obesity treatment is available only to those with adequate insurance coverage or financial resources.

Geographic disparities in access to specialized pediatric obesity care may further complicate equitable distribution of these therapies. Rural and underserved communities may face additional barriers to accessing both the medications and the comprehensive monitoring required for safe use.

Stigma and Medicalization

The introduction of pharmacotherapy for pediatric obesity must be carefully considered in the context of weight stigma and the medicalization of body weight. There is a risk that emphasizing pharmaceutical interventions may inadvertently reinforce harmful stereotypes about obesity being solely a medical problem rather than a complex condition influenced by genetic, environmental, and social factors.

Discussion

Integration with Comprehensive Care

The evidence suggests that GLP-1 RAs should not be viewed as standalone treatments but rather as components of comprehensive obesity management programs. Rather than broadly applying this therapy if it is approved, we suggest careful patient selection and monitoring by clinicians pending further studies [48].

Effective integration requires multidisciplinary teams including pediatric endocrinologists, registered dietitians, mental health professionals, and exercise physiologists. This perspective serves as a call to action for research and clinical innovation to address the psychosocial effects of GLP-1s on adolescents. Screening, monitoring, and future research will be key to ensuring safe and effective use of GLP-1 therapy as well as optimal psychosocial outcomes for youth utilizing GLP-1 medications for obesity treatment [49].

Patient Selection Criteria

The development of clear patient selection criteria is vital for optimizing outcomes and minimizing risks. However, heterogeneity in weight loss response, cost, side effects, and need for injections may limit their use in many pediatric patients. Rather than broadly applying this therapy if it is approved, we suggest careful patient selection and monitoring by clinicians pending further studies [50].

Potential selection criteria might include:

- Adolescents with BMI ≥95th percentile for age and sex

- History of unsuccessful comprehensive lifestyle interventions

- Presence of obesity-related comorbidities

- Absence of contraindications (eating disorders, severe mental illness)

- Adequate family support and resources for monitoring

- Informed consent and assent processes completed

Monitoring and Follow-up

Comprehensive monitoring protocols are essential for safe and effective use of GLP-1 RAs in adolescents. Therefore, it is important to monitor patients during the treatment and screen for preexisting mental health conditions [51].

Monitoring should include:

- Regular weight and BMI measurements

- Assessment of metabolic parameters

- Mental health screening and evaluation

- Monitoring for adverse events

- Assessment of medication adherence

- Evaluation of lifestyle behaviors

Future Research Priorities

Several critical research questions remain unanswered. However, further research is needed to elucidate long-term safety and efficacy outcomes and to address potential disparities in access to care [52].

Priority research areas include:

- Long-term safety studies extending beyond 2-3 years

- Comparative effectiveness research comparing different GLP-1 RAs

- Studies examining optimal treatment duration and discontinuation strategies

- Research on predictors of treatment response

- Health economic analyses specific to pediatric populations

- Investigation of combination therapies

- Studies addressing health equity and access barriers

Policy Implications

The use of GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) for pediatric obesity presents important considerations for health policy. As traditional lifestyle and behavioral interventions often yield variable outcomes, and with rising projections of childhood obesity, pharmacological treatment options like GLP-1 RAs are becoming increasingly relevant. To support effective integration of these therapies, health systems and policymakers should explore reimbursement and pricing strategies that enhance access. Ensuring that cost-effective therapies are available can improve population-level health outcomes and help reduce long-term healthcare expenditures.

Key policy areas that require attention include:

- Clinical Practice Guidelines: Development of standardized, evidence-based guidelines for the use of GLP-1 RAs in children and adolescents, including indications, dosing, and monitoring.

- Insurance Coverage and Prior Authorization: Clear policies outlining coverage criteria, prior authorization processes, and cost-sharing mechanisms to ensure timely and equitable access.

- Prescriber Training and Certification: Implementation of training programs and credentialing requirements for clinicians to ensure appropriate and safe prescribing of GLP-1 RAs in pediatric populations.

- Quality Metrics and Outcome Monitoring: Establishment of systems to track clinical outcomes, monitor adverse events, and evaluate the long-term effectiveness and safety of these therapies in real-world settings.

- Equity in Access: Strategies to address disparities in access to care, including support for underserved communities, outreach programs, and culturally appropriate care models.

Limitations and Considerations

Current Evidence Limitations

The current evidence base for GLP-1 RAs in adolescents has several important limitations. As of this review, only one large randomized clinical trial of semaglutide in youth has been completed, with a follow-up duration of 68 weeks [54]. This limited duration of follow-up raises questions about long-term efficacy and safety.

The heterogeneity of study populations and interventions across different trials makes it challenging to draw definitive conclusions about optimal treatment approaches. Our results were limited by high interstudy heterogeneity, paucity of literature, and lack of controlled trials [55].

Generalizability Concerns

Most clinical trials have been conducted in specialized research settings with intensive monitoring and support. The generalizability of these results to real-world clinical practice remains uncertain. Community-based studies are needed to understand how these medications perform in typical clinical settings.

Developmental Considerations

The use of GLP-1 RAs during adolescence, a critical period of physical and psychological development, requires careful consideration. The long-term effects of these medications on growth, development, and psychological well-being are not fully understood.

Conclusion

The question of whether to prescribe GLP-1 agonists for adolescents with obesity does not have a simple answer. The evidence demonstrates that these medications can be effective tools for weight management in carefully selected adolescents, offering hope for those who have not responded to lifestyle interventions alone. However, their use must be balanced against significant considerations including safety concerns, high costs, and the need for comprehensive monitoring and support.

The current evidence suggests that GLP-1 RAs should be considered as part of a comprehensive obesity management strategy for adolescents who meet specific criteria, including failure of lifestyle interventions, presence of comorbidities, and adequate support systems. The decision to prescribe these medications should involve careful consideration of individual patient factors, thorough informed consent processes, and commitment to ongoing monitoring and support.

Several key principles should guide clinical decision-making:

- Individualized Care: Each adolescent should be evaluated individually, considering their medical history, psychosocial situation, and treatment goals.

- Comprehensive Approach: GLP-1 RAs should be integrated into comprehensive obesity management programs that include lifestyle counseling, behavioral support, and ongoing monitoring.

- Risk-Benefit Assessment: The potential benefits must be carefully weighed against known and unknown risks, particularly given the limited long-term safety data in adolescents.

- Shared Decision-Making: Treatment decisions should involve the adolescent, their family, and a multidisciplinary healthcare team.

- Ongoing Monitoring: Regular assessment of efficacy, safety, and psychosocial outcomes is essential throughout treatment.

- Equity Considerations: Efforts must be made to ensure equitable access to these therapies while addressing cost and insurance coverage barriers.

The introduction of GLP-1 RAs for pediatric obesity represents both an opportunity and a challenge. While these medications offer new hope for adolescents struggling with obesity, their use must be guided by evidence-based protocols, careful patient selection, and ongoing research to address remaining knowledge gaps.

Future research should focus on long-term outcomes, optimal treatment protocols, patient selection criteria, and strategies to ensure equitable access. As our understanding of these medications continues to evolve, clinical practice guidelines should be regularly updated to reflect new evidence and best practices.

The obesity epidemic affecting our youth requires innovative approaches, and GLP-1 RAs may represent an important advancement in our therapeutic armamentarium. However, their use must be implemented thoughtfully, with careful attention to both the opportunities they provide and the challenges they present. Only through this balanced approach can we ensure that these potentially transformative therapies are used safely and effectively to improve the health and well-being of adolescents with obesity.

The decision to prescribe GLP-1 agonists for adolescents should ultimately be made on a case-by-case basis, considering the individual patient’s circumstances, the availability of alternative treatments, and the commitment of the healthcare team to provide comprehensive, ongoing care. As we move forward, continued research, careful monitoring, and collaborative efforts between healthcare providers, researchers, policymakers, and families will be essential to optimize the use of these medications and improve outcomes for adolescents with obesity.

References:

- Altamimi, M., et al. (2021). Safety and efficacy of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in children and adolescents with obesity: A meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatrics, 239, 84-91.

- Stefater-Richards, M. A., et al. (2025). GLP-1 receptor agonists in pediatric and adolescent obesity. Pediatrics, 155(4), e2024068119.

- Chadda, K. R., et al. (2021). GLP-1 agonists for obesity and type 2 diabetes in children: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews, 22(6), e13177.

- Censani, M., et al. (2020). Role of GLP-1 receptor agonists in pediatric obesity: Benefits, risks, and approaches to patient selection. Current Obesity Reports, 9(4), 522-532.

- Kavarian, P. N., et al. (2024). Use of glucagon-like-peptide 1 receptor agonist in the treatment of childhood obesity. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 36(5), 542-546.

- Goke, B., et al. (2025). GLP-1 receptor agonists for treatment of pediatric obesity: Behavioral health considerations. Pediatrics, 155(4), e2024068120.

- Agosta, M., et al. (2024). Efficacy of liraglutide in pediatric obesity: A review of clinical trial data. Obesity Medicine, 48, 100545.

- Katole, N. T., et al. (2024). The antiobesity effect and safety of GLP-1 receptor agonist in overweight/obese adolescents without diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus, 16(8), e66280.

- Saldaña-Ruiz, S., et al. (2024). Metabolic outcomes and safety of GLP-1 receptor agonists in children and adolescents with obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatric Obesity, 19(12), e13156.

- Nass, R., et al. (2023). Emerging role of GLP-1 agonists in obesity: A comprehensive review of randomised controlled trials. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome, 17(7), 102798.

- Weghuber, D., et al. (2022). Once-weekly semaglutide in adolescents with obesity. New England Journal of Medicine, 387(24), 2245-2257.

- Weghuber, D., et al. (2023). Reducing BMI below the obesity threshold in adolescents treated with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg. Obesity, 31(6), 1641-1650.

- Agosta, M., et al. (2024). Efficacy of liraglutide in pediatric obesity: A review of clinical trial data. Obesity Medicine, 48, 100545.

- Gokul, P. R., et al. (2024). Semaglutide, a long-acting GLP-1 analogue, for the management of early-onset obesity due to MC4R defect: A case report. Hormone Research in Paediatrics, 98(2), 148-155.

- Frias, J. P., et al. (2022). Semaglutide 2.4-mg injection as a novel approach for chronic weight management. American Journal of Medicine, 135(12), 1454-1464.

- Blundell, J., et al. (2024). Once-weekly semaglutide in persons with obesity and knee osteoarthritis. New England Journal of Medicine, 391(25), 2347-2357.

- Wilding, J. P. H., et al. (2021). Potential implications of the FDA approval of semaglutide for overweight and obese adults in the United States. Obesity, 29(11), 1789-1790.

- Bensignor, M. O., et al. (2024). Semaglutide for management of obesity in adolescents: Efficacy, safety, and considerations for clinical practice. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 36(4), 449-455.

- Chao, A. M., et al. (2022). Semaglutide for the treatment of obesity. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine, 33(3), 159-166.

- Hsu, J., et al. (2024). Emerging pharmacotherapies for obesity: A systematic review. Pharmacotherapy, 44(2), 234-252.

- Zhang, X., et al. (2024). Global prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 178(8), 800-813.

- de Onis, M., et al. (2024). Global prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity among preschool children. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 119(3), 675-688.

- GBD 2021 US Obesity Forecasting Collaborators. (2024). National-level and state-level prevalence of overweight and obesity among children, adolescents, and adults in the USA, 1990-2021, and forecasts up to 2050. Lancet, 404(10469), 2278-2298.

- Shastri, S., et al. (2024). Childhood obesity in India: A two-decade meta-analysis of prevalence and socioeconomic correlates. Lancet Regional Health – Southeast Asia, 14, 100210.

- GBD 2021 US Obesity Forecasting Collaborators. (2024). National-level and state-level prevalence of overweight and obesity among children, adolescents, and adults in the USA, 1990-2021, and forecasts up to 2050. Lancet, 404(10469), 2278-2298.

- Salam, R. A., et al. (2022). Childhood obesity: Prevalence and prevention in modern society. Nutrients, 14(22), 4756.

- Cunningham, S. A., et al. (2019). Understanding recent trends in childhood obesity in the United States. Pediatrics, 143(4), e20183170.

- Deckelbaum, R. J., et al. (1997). Pediatric obesity: An overview of etiology and treatment. Pediatrics, 99(6), 804-807.

- Stavridou, A., et al. (2024). Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity over the last 20 years. Nutrients, 16(24), 4285.

- Branner, C. M., et al. (2008). Racial and ethnic differences in pediatric obesity-prevention counseling: National prevalence of clinician practices. Obesity, 16(3), 690-694.

- Altamimi, M., et al. (2021). Safety and efficacy of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in children and adolescents with obesity: A meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatrics, 239, 84-91.

- Arillotta, D., et al. (2024). GLP-1 agonists and risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviours: Confound by indication once again? A narrative review. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 83, 10-19.

- Anderberg, R. H., et al. (2015). GLP-1 is both anxiogenic and antidepressant; divergent effects of acute and chronic GLP-1 on emotionality. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 65, 54-66.

- Koller, D., et al. (2025). The effect of GLP-1RAs on mental health and psychotropics-induced metabolic disorders: A systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 162, 106978.

- Nauck, M. A., et al. (2015). Adverse effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists. Diabetologia, 58(7), 1404-1412.

- Arillotta, D., et al. (2023). GLP-1 receptor agonists and related mental health issues; insights from a range of social media platforms using a mixed-methods approach. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 167, 84-94.

- Petersen, M. C., et al. (2024). Glucagon-like receptor-1 agonists for obesity: Weight loss outcomes, tolerability, side effects, and risks. Obesity Pillars, 11, 100113.

- Zhu, J., et al. (2024). The antidepressant effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 27(1), pyad071.

- Jørgensen, N. B., et al. (2022). GLP-1 agonists: Superior for mind and body in antipsychotic-treated patients? Pharmacopsychiatry, 55(4), 167-177.

- Mansur, R. B., et al. (2023). Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists as a protective factor for incident depression in patients with diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 322, 1-9.

- Polinski, J. M., et al. (2023). Cost-effectiveness analysis of five anti-obesity medications from a US payer’s perspective. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases, 33(8), 1570-1579.

- Pang, B., et al. (2022). Cost-effectiveness analysis of 4 GLP-1RAs in the treatment of obesity in a US setting. Annals of Translational Medicine, 10(8), 466.

- Chadda, K. R., et al. (2021). GLP-1 agonists for obesity and type 2 diabetes in children: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews, 22(6), e13177.

- Wang, J., et al. (2023). Value of GLP-1 receptor agonists versus long-acting insulins for type 2 diabetes patients with and without established cardiovascular or chronic kidney diseases: A model-based cost-effectiveness analysis using real-world data. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 199, 110634.

- Neff, K. J., et al. (2024). A cost comparison of GLP-1 receptor agonists and bariatric surgery: What is the break even point? Obesity Surgery, 34(10), 3542-3548.

- Kuo, I. C., et al. (2024). Economic evaluation of weight loss and transplantation strategies for kidney transplant candidates with obesity. Clinical Transplantation, 38(11), e15436.

- Altamimi, M., et al. (2021). Safety and efficacy of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in children and adolescents with obesity: A meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatrics, 239, 84-91.

- Katole, N. T., et al. (2024). The antiobesity effect and safety of GLP-1 receptor agonist in overweight/obese adolescents without diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus, 16(8), e66280.

- Censani, M., et al. (2020). Role of GLP-1 receptor agonists in pediatric obesity: Benefits, risks, and approaches to patient selection. Current Obesity Reports, 9(4), 522-532.

- Lamarre, S., et al. (2024). Cost-effectiveness of semaglutide in patients with obesity and cardiovascular disease. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 41(1), 141-149.

- Deng, Y., et al. (2024). Efficacy of lifestyle interventions to treat pediatric obesity: A systematic review and multivariate meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obesity Reviews, 25(11), e13817.

- Reinehr, T. (2013). Lifestyle intervention in childhood obesity: Changes and challenges. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity, 8(4), 273-282.

- Tucker, J. M., et al. (2022). Editorial: Lifestyle interventions for childhood obesity: Broadening the reach and scope of impact. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 13, 1099534.

- McGovern, L., et al. (2008). Clinical review: Treatment of pediatric obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 93(12), 4600-4605.

- Chimatapu, S. N., et al. (2024). Wearable devices beyond activity trackers in youth with obesity: Summary of options. Childhood Obesity, 20(3), 208-218.

- Hagman, E., et al. (2025). Long-term results of a digital treatment tool as an add-on to pediatric obesity lifestyle treatment: A 3-year pragmatic clinical trial. International Journal of Obesity, 49(3), 456-464.

- Altman, M., et al. (2014). Systematic review and meta-analysis of comprehensive behavioral family lifestyle interventions addressing pediatric obesity. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39(8), 809-825.

- Boodai, S. A., et al. (2019). Prevention and treatment of pediatric obesity: A strategy involving children, adolescents and the family for improved body composition. Seminars in Pediatric Surgery, 28(4), 150-157.

- Ryder, J. R., et al. (2021). Childhood obesity: A review of current and future management options. Obesity Reviews, 22(12), e13348.

- Epstein, L. H., et al. (2010). Future directions for pediatric obesity treatment. Obesity, 18(S1), S8-S12.

References

[1] National-level and state-level prevalence of overweight and obesity among children, adolescents, and adults in the USA, 1990-2021, and forecasts up to 2050 – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39551059/

[2] Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity over the last 20 years – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39709095/

[3] National-level and state-level prevalence of overweight and obesity among children, adolescents, and adults in the USA, 1990–2021, and forecasts up to 2050 – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673624015484

[4] Pediatric obesity. An overview of etiology and treatment – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9130924/

[5] Safety and Efficacy of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: A Meta-Analysis – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022347621004327

[6] Systematic review and meta-analysis of comprehensive behavioral family lifestyle interventions addressing pediatric obesity – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24824614/

[7] Semaglutide 2.4-mg injection as a novel approach for chronic weight management – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36525677/

[8] Safety and Efficacy of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: A Meta-Analysis – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022347621004327

[9] Safety and Efficacy of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: A Meta-Analysis – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022347621004327

[10] Reducing BMI below the obesity threshold in adolescents treated with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37196421/

[11] Role of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Pediatric Obesity: Benefits, Risks, and Approaches to Patient Selection – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33085056/

[12] Role of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Pediatric Obesity: Benefits, Risks, and Approaches to Patient Selection – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33085056/

[13] The Antiobesity Effect and Safety of GLP-1 Receptor Agonist in Overweight/Obese Adolescents Without Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39238716/

[14] Efficacy of liraglutide in pediatric obesity: A review of clinical trial data – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2451847624000150

[15] The Antidepressant Effects of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1064748123003949

[16] The Antidepressant Effects of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1064748123003949

[17] The effect of GLP-1RAs on mental health and psychotropics-induced metabolic disorders: A systematic review – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0306453025001386

[18] Metabolic outcomes and safety of GLP-1 receptor agonists in children and adolescents with obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40269110/

[19] Adverse Effects of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26177483/

[20] Use of glucagon-like-peptide 1 receptor agonist in the treatment of childhood obesity – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39254757/

[21] Glucagon-like Receptor-1 agonists for obesity: Weight loss outcomes, tolerability, side effects, and risks – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2667368124000299

[22] Glucagon-like Receptor-1 agonists for obesity: Weight loss outcomes, tolerability, side effects, and risks – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2667368124000299

[23] Role of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Pediatric Obesity: Benefits, Risks, and Approaches to Patient Selection – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33085056/

[24] Use of glucagon-like-peptide 1 receptor agonist in the treatment of childhood obesity – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39254757/

[25] Safety and Efficacy of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: A Meta-Analysis – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022347621004327

[26] Semaglutide for the treatment of obesity – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34942372/

[27] Metabolic outcomes and safety of GLP-1 receptor agonists in children and adolescents with obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40269110/

[28] The Antidepressant Effects of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1064748123003949

[29] Adverse Effects of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26177483/

[30] GLP-1 Receptor Agonists for Treatment of Pediatric Obesity: Behavioral Health Considerations – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40306953/

[31] Semaglutide for the treatment of obesity – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34942372/

[32] Semaglutide 2.4-mg injection as a novel approach for chronic weight management – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36525677/

[33] Systematic review and meta-analysis of comprehensive behavioral family lifestyle interventions addressing pediatric obesity – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24824614/

[34] Understanding recent trends in childhood obesity in the United States – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30910341/

[35] Safety and Efficacy of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: A Meta-Analysis – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022347621004327

[36] A cost comparison of GLP-1 receptor agonists and bariatric surgery: what is the break even point? – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39285034/

[37] A cost comparison of GLP-1 receptor agonists and bariatric surgery: what is the break even point? – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39285034/

[38] Economic evaluation of weight loss and transplantation strategies for kidney transplant candidates with obesity – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1600613524004465

[39] Economic evaluation of weight loss and transplantation strategies for kidney transplant candidates with obesity – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1600613524004465

[40] A cost comparison of GLP-1 receptor agonists and bariatric surgery: what is the break even point? – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39285034/

[41] Semaglutide for the treatment of obesity – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34942372/

[42] Role of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Pediatric Obesity: Benefits, Risks, and Approaches to Patient Selection – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33085056/

[43] The Antiobesity Effect and Safety of GLP-1 Receptor Agonist in Overweight/Obese Adolescents Without Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39238716/

[44] A cost comparison of GLP-1 receptor agonists and bariatric surgery: what is the break even point? – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39285034/

[45] A cost comparison of GLP-1 receptor agonists and bariatric surgery: what is the break even point? – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39285034/

[46] GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Pediatric and Adolescent Obesity – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40031990/

[47] Semaglutide for the treatment of obesity – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34942372/

[48] Role of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Pediatric Obesity: Benefits, Risks, and Approaches to Patient Selection – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33085056/

[49] GLP-1 Receptor Agonists for Treatment of Pediatric Obesity: Behavioral Health Considerations – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40306953/

[50] Role of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Pediatric Obesity: Benefits, Risks, and Approaches to Patient Selection – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33085056/

[51] Adverse Effects of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26177483/

[52] Use of glucagon-like-peptide 1 receptor agonist in the treatment of childhood obesity – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39254757/

[53] A cost comparison of GLP-1 receptor agonists and bariatric surgery: what is the break even point? – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39285034/

[54] Semaglutide for the treatment of obesity – PubMed – pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govhttps://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34942372/

[55] Value of GLP-1 receptor agonists versus long-acting insulins for type 2 diabetes patients with and without established cardiovascular or chronic kidney diseases: A model-based cost-effectiveness analysis using real-world data – ScienceDirect –https://www.sciencedirect.com/

science/article/abs/pii/S0168822723001006