Silent Warning Signs: Why Stroke Rates Are Surging Among People Under 40

Please like and subscribe if you enjoyed this video 🙂 Brief summary – refer to full article below.

Introduction

Stroke prevalence has increased by 8% overall between 2011-2013 and 2020-2022. More concerning, however, is the sharp rise among younger adults. Recent data show a 14.6% increase in stroke cases among those aged 18-44 and a 15.7% increase among those aged 45-64, marking a significant shift in stroke epidemiology.

In northern Colorado, strokes in individuals aged 18-45 nearly doubled, from 5% in 2020 to 9% by mid-2023. Once considered rare in younger people, strokes now account for an estimated 10-14% of all cases, prompting urgent questions about emerging risk factors and the need for earlier clinical intervention.

Several trends underscore this shift:

- The average age at stroke onset is steadily decreasing.

- Nearly one in four adults aged 18–39 has hypertension, significantly elevating stroke risk.

- Around 50% of young adults who experience strokes have high blood pressure.

Moreover, certain causes of stroke are more common in younger individuals. Cervical artery dissection, for example, accounts for 10–25% of strokes in this group, far more frequently than in older adults. The prothrombotic effects associated with COVID-19 may also be contributing to increased stroke incidence.

Epidemiological data reflect this trend: stroke rates among adults aged 20–44 rose from 17 per 100,000 in 1993 to 28 per 100,000 in 2015.

As stroke becomes increasingly prevalent in younger populations, understanding its unique causes and risk profiles is critical. Early identification, targeted prevention, and tailored treatment strategies are essential to address this evolving public health challenge.

The changing face of stroke: Why age is no longer a barrier

Traditionally perceived as a disease of older age, stroke now presents a changing demographic landscape, with alarming increases among younger populations. This shift challenges long-held assumptions about who faces stroke risk and necessitates new approaches to prevention and treatment.

Rising incidence in people under 40

The incidence of stroke among individuals under 50 has grown significantly, now accounting for approximately 10% of all cases [1]. In the U.S., the average age of stroke onset is declining. Among adults aged 20-44, stroke incidence rose from 17 per 100,000 in 1993 to 28 per 100,000 in 2015 [1].

This trend is consistent across other regions:

- In the Netherlands, incidence among young adults rose from 14.0 to 17.2 per 100,000 person-years between 1998 and 2010 [1].

- A 27-year French study showed ischemic stroke rates in adults under 55 nearly doubled, from 11.6 to 20.2 per 100,000 [1].

- In India, stroke rates reached 41 per 100,000 in the 40-44 age group [1].

Notably, these increases occur despite declining overall stroke rates in many high-income countries [2].

Comparison with older age groups

Data consistently show divergent trends in stroke incidence when comparing younger and older populations. A population-based study in the United Kingdom revealed a 67% increase in stroke incidence among individuals younger than 55 (IRR 1.67), in contrast to a 15% decrease in those aged 55 and older (IRR 0.85) [3].

Furthermore, in 2014, 38% of all hospitalizations for stroke involved individuals under 65 years of age [4], indicating that strokes in younger adults are not rare or exceptional.

Even within the 35-44 age bracket, hospitalizations for ischemic stroke rose from 28.2 to 38.6 per 10,000 between 1995 and 2008 [2].

While the prevalence of stroke in adults aged 65 and above remains the highest (7.7%) [5], incidence rates in this group have largely stabilized, unlike the rising trend observed in younger cohorts.

Why this trend matters clinically

Although younger patients typically experience lower immediate mortality rates compared to older adults, the long-term impact can be profound. Many young stroke survivors face chronic neurological deficits that persist for years, including:

- Cognitive impairment

- Epilepsy

- Post-stroke fatigue

- Depression and anxiety

- Loss of functional independence

These effects can significantly interfere with education, employment, and family life, leading to decades of disability.

The economic impact of early-onset stroke is also substantial. Indirect costs, including lost income, reduced productivity, and caregiver burden, are estimated to be more than six times higher in adults under 65 compared to older stroke survivors [2], primarily due to their greater lifetime earnings potential and workforce participation.

The rise in stroke among younger adults is further complicated by persistent racial and ethnic disparities.

Black and Hispanic individuals not only experience higher rates of ischemic stroke at younger ages but also often have worse post-stroke outcomes, despite similar access to acute treatments such as tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and mechanical thrombectomy [1].

These disparities are influenced by multiple factors, including:

- Higher prevalence of risk factors (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, obesity) at younger ages

- Differences in social determinants of health (e.g., access to preventive care, education, income)

- Structural inequities within healthcare systems

These findings highlight the need for culturally tailored public health interventions, earlier screening, and targeted prevention strategies within vulnerable communities.

Unpacking the causes: What’s driving strokes in young adults?

Understanding the drivers behind young adult stroke requires examining multiple risk categories that contribute to this alarming trend. The causes span from traditional risk factors to emerging concerns specific to younger demographics.

Traditional risk factors: hypertension, diabetes, obesity

The classic stroke risk factors remain powerful predictors even in younger populations. Hypertension stands as the most common modifiable risk factor in young adults with stroke, present in approximately 39-48% of cases. Among young adults who experience stroke, nearly 50% have high blood pressure—a rate much higher than their non-stroke peers. Diabetes affects 21-25% of young stroke patients, while obesity impacts up to 32%, often creating a cascade of metabolic disruptions that increase stroke risk. Particularly concerning, these conditions are increasingly diagnosed at younger ages, accelerating vascular damage.

Emerging contributors: drug use, COVID-19, sedentary lifestyle

Beyond traditional factors, newer contributors have gained attention. Recreational drug use, especially cocaine and methamphetamines, causes up to 10% of strokes in young adults—five times higher than rates seen in older populations. Since 2020, COVID-19 has emerged as a substantial risk factor, with infected patients showing a 3-8 times higher stroke risk in the first two weeks after diagnosis. This risk persists even in mild cases. Consequently, pandemic lifestyle changes have exacerbated sedentary behaviors, further amplifying risk profiles.

Unique causes: cervical artery dissection, PFO, clotting disorders

Several etiologies are more common or even exclusive to younger individuals:

- Cervical artery dissection accounts for 10–25% of strokes in adults under 45 and may follow minor trauma or neck strain (e.g., from sports or chiropractic manipulation).

- Patent foramen ovale (PFO) is found in up to 25% of young patients with ischemic stroke, compared to around 10% in the general population, providing a conduit for paradoxical embolism.

- Inherited or acquired clotting disorders, such as factor V Leiden mutation and antiphospholipid syndrome, disproportionately affect young adults and are often overlooked in standard workups.

Gender-specific risks: pregnancy, oral contraceptives

For women under 40, hormonal factors introduce unique vulnerabilities. Pregnancy increases stroke risk 3-fold, with the highest risk occurring in the third trimester and first six weeks postpartum. Hormonal contraceptives containing estrogen can double stroke risk, particularly when combined with smoking or migraine with aura.

Recognizing the signs: When symptoms are easy to miss

As stroke incidence rises among young adults, early recognition of symptoms is more important than ever. However, strokes in this age group often present differently from classical cases, posing a diagnostic challenge for clinicians. Timely recognition of these subtle or atypical signs is vital to avoid missed opportunities for intervention.

Common symptoms in younger patients

While traditional symptoms such as facial drooping, arm weakness, and slurred speech may still occur, younger patients are more likely to experience atypical signs, particularly with posterior circulation strokes. These may include:

- Vertigo or a spinning sensation

- Imbalance or unilateral leg weakness

- Visual disturbances (e.g., double vision, visual field loss)

- Sudden, severe headache

- Nausea and vomiting

Registry data show that younger stroke patients more frequently present with isolated sensory deficits, acute confusion, monoparesis, or neuropsychiatric symptoms¹. Persistent neck pain after minor trauma or sudden head movements may also indicate cervical artery dissection, a common stroke mechanism in this population¹.

Stroke mimics: migraines, MS, anxiety

Approximately 20-50% of suspected stroke cases turn out to be “stroke mimics”—conditions with stroke-like presentations [6]. These mimics occur more frequently in younger, female patients with less severe symptoms [7]. Common neurological mimics include seizures (19.7%), migraines (18.8%), and peripheral neuropathies (11.2%) [6]. Non-neurological conditions like cardiovascular issues (15.9%), psychiatric disorders (11.9%), and infections (8.9%) also mimic stroke presentations [6].

Interestingly, research suggests the psychological impact of stroke mimics may exceed that of actual strokes, with higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder developing within a month after the event [7].

BE FAST vs. FAST: updated tools for early detection

The traditional FAST mnemonic (Face, Arm, Speech, Time) is widely used but has limitations. It misses about 14% of all ischemic strokes[⁸] and fails to detect up to 40% of posterior circulation strokes, which often present with imbalance or visual symptoms[⁹].

To address these gaps, the BE FAST acronym adds two key elements:

- B – Balance (unsteadiness or leg weakness)

- E – Eyes (sudden vision changes)

Incorporating these improves detection rates significantly, reducing missed cases from 14.1% to just 4.4%[⁸]. However, while BE FAST enhances accuracy, studies show it may be harder for the general public to remember compared to the simpler FAST version[¹⁰].

Mechanisms and diagnosis: How strokes happen in the young

The pathophysiology of stroke in young adults involves distinct mechanisms that require specialized diagnostic approaches. Understanding these processes is essential for proper identification and treatment.

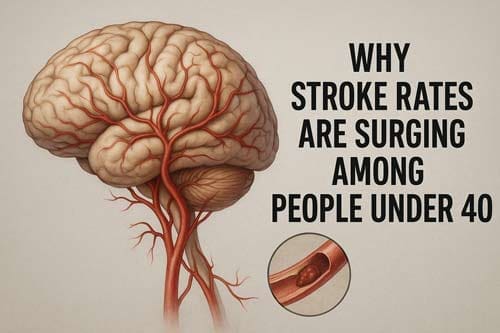

Ischemic vs. hemorrhagic strokes

Ischemic strokes comprise approximately 87% of all strokes, with hemorrhagic strokes accounting for the remaining 13% [11]. In young adults, this distribution generally holds true, though with some notable variations:

- Ischemic strokes typically result from arterial blockage by thrombi (blood clots), emboli, or arterial dissections

- Hemorrhagic strokes occur when weakened vessels rupture, creating either subarachnoid hemorrhages (between brain and meninges) or intracerebral hemorrhages (within brain tissue)

Unlike older patients, young adults with ischemic strokes often exhibit non-atherosclerotic mechanisms. Cortical infarcts in this population frequently stem from cardioembolic causes, whereas deep structural infarcts commonly result from non-atherosclerotic vasculopathy [12].

Arterial dissection and cardioembolism

Cervical artery dissection contributes to 2% of all ischemic strokes yet accounts for up to 25% of ischemic strokes in adults under 50 [13]. This condition involves arterial wall tears that create intraluminal thrombi, stenosis, occlusion, or aneurysms.

Cardioembolism represents another primary mechanism. Patent foramen ovale (PFO) appears in up to 45% of young cryptogenic stroke patients [1]. Subsequently, other cardiac sources include atrial fibrillation and intracardiac thrombi, though these remain less common in younger populations.

Role of imaging: CT, MRI, and angiography

Initial evaluation typically requires non-contrast CT to exclude hemorrhage [14]. However, MRI offers superior detection for:

- Early ischemic changes (within minutes of onset)

- Posterior fossa lesions (brainstem, cerebellum)

- Small infarcts in deep structures

For suspected dissection, CTA or MRA with T1-fat saturation sequences provides detailed visualization [4]. Digital subtraction angiography remains the gold standard for defining luminal abnormalities but is increasingly reserved for interventional scenarios [13].

When to suspect rare causes

Certain clinical presentations warrant investigation for uncommon etiologies. Consider cerebral venous thrombosis in young women, particularly those using oral contraceptives or during pregnancy/postpartum periods [15]. Likewise, infarcts that don’t follow classic arterial territories suggest venous pathology [16].

Migraines with aura deserve attention, as they account for nearly 35% of strokes in young women and 20% in young men under 35 [17].

Conclusion

The shifting paradigm: What clinicians need to know

The rising incidence of stroke among younger populations represents a paradigm shift in stroke epidemiology. Throughout this article, we have examined how this once “disease of aging” now increasingly affects those under 40, creating new challenges for detection, diagnosis, and treatment.

First and foremost, clinicians must recognize that age no longer serves as a reliable protective factor against stroke. The data clearly demonstrates this trend:

- Stroke prevalence increased by 14.6% for ages 18-44

- Nearly doubled rates in some regions for adults 18-45

- Incidence rates climbing from 17 to 28 per 100,000 in young adults

Although traditional risk factors like hypertension remain relevant, younger patients present with unique etiologies that require specialized consideration. Consequently, cervical artery dissection, patent foramen ovale, and recreational drug use demand particular attention during evaluation of young adults with stroke-like symptoms.

Furthermore, the BE FAST protocol offers substantial advantages over the conventional FAST approach, especially for detecting posterior circulation events common in younger patients. Clinicians should therefore implement this expanded screening tool in emergency settings.

The economic and social implications of these trends cannot be overstated. Unlike older stroke patients, young survivors face decades of potential disability during their most productive years. Additionally, racial disparities compound these concerns, with higher incidence rates among Black and Hispanic individuals at younger ages.

During the diagnostic process, practitioners should maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating young adults with neurological complaints. Undoubtedly, specialized imaging protocols including MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging and vessel-specific sequences offer superior detection of subtle findings often missed on standard CT scans.

The convergence of traditional risk factors with modern lifestyle elements, specifically, sedentary behavior, stress, substance use, and pandemic-related complications—creates a perfect storm for continued increases in young adult stroke rates. Therefore, preventive strategies must evolve to address these multifaceted contributors through comprehensive risk assessment and targeted interventions.

Above all, education remains our most powerful tool against this troubling trend. Both healthcare providers and the public require awareness that stroke can and does occur at any age, with potentially devastating consequences when recognition is delayed. While further research is certainly needed to fully understand these shifting patterns, clinicians must adapt their practice now to meet this growing challenge.

Frequently Asked Questions:

FAQs

Q1. How prevalent are strokes among people under 40? Strokes in young adults are becoming increasingly common. Approximately 10-14% of all stroke cases now occur in people under 45. In some regions, stroke rates for adults aged 18-45 have nearly doubled in recent years, with incidence rates rising from 17 to 28 per 100,000 in young adults.

Q2. What are the warning signs of a stroke in younger adults? Young adults may experience both classic and atypical stroke symptoms. Besides facial drooping and arm weakness, look out for sudden vertigo, imbalance, visual problems, severe headache, and nausea. The BE FAST acronym (Balance, Eyes, Face, Arm, Speech, Time) is an updated tool for recognizing stroke symptoms, particularly effective for detecting strokes in younger patients.

Q3. Can lifestyle factors contribute to stroke risk in young people? Yes, several lifestyle factors can increase stroke risk in young adults. These include sedentary behavior, obesity, smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and recreational drug use. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has been linked to increased blood clotting abnormalities, potentially elevating stroke risk even in mild cases.

Q4. Are there unique stroke risks for young women? Young women face additional stroke risks due to hormonal factors. Pregnancy increases stroke risk 3-fold, with the highest risk in the third trimester and first six weeks postpartum. Hormonal contraceptives containing estrogen can double stroke risk, especially when combined with smoking or migraine with aura.

Q5. How are strokes in young adults diagnosed? Diagnosing strokes in young adults often requires specialized imaging. While initial evaluation typically uses non-contrast CT to exclude hemorrhage, MRI offers superior detection of early ischemic changes and small infarcts. For suspected arterial dissection, CTA or MRA with T1-fat saturation sequences provides detailed visualization. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating young adults with neurological complaints.

References:

[1] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10420127/

[2] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7008634/

[3] – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35943470/

[4] – https://www.stroke-manual.com/arterial-dissection/

[5] – https://healthmatters.nyp.org/what-to-know-about-the-rising-stroke-rates-in-younger-people/

[6] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7939567/

[7] – https://www.heart.org/en/news/2024/02/02/when-symptoms-suggest-a-stroke-but-its-something-else

[8] – https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015169

[9] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8837419/

[10] – https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/JAHA.123.035696

[11] – https://www.massgeneralbrigham.org/en/about/newsroom/articles/ischemic-vs-hemorrhagic-stroke

[12] – https://ecommons.aku.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1144&context=pakistan_fhs_mc_med_neurol

[13] – https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000457

[14] – https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546635/

[15] – https://www.stroke.org/en/about-stroke/stroke-risk-factors/uncommon-causes-of-stroke

[16] – https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572000/

[17] – https://www.heart.org/en/news/2024/03/26/strokes-in-young-adults-may-be-caused-more-often-by-migraines-other-nontraditional-factors