Sepsis-3 vs CMS Core Measures: Which Definition Should You Use?

Introduction

Sepsis core measures remain at the center of a critical clinical debate as sepsis continues to devastate healthcare systems nationwide. Each year, the incidence of severe sepsis increases by approximately 13% in the United States, with at least 1.7 million U.S. adults developing sepsis annually and at least 350,000 dying as a result. The financial burden is equally staggering—sepsis accounted for more than $20 billion or 5.2% of total hospital costs in 2011, while recent Medicare data shows the annual sepsis spend now exceeds $40 billion.

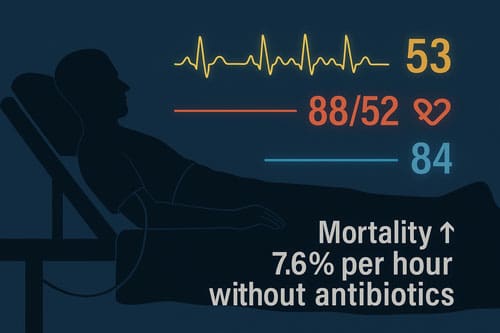

Choosing between Sepsis-3 criteria and CMS SEP-1 core measures presents healthcare providers with substantial challenges that affect both patient outcomes and institutional metrics. Studies indicate that using current SEP-1 criteria may result in potential overdiagnosis rates of 20-30% compared to Sepsis-3 criteria, potentially representing 340,000 hospitalizations annually. However, timely intervention remains crucial regardless of definition—for every hour without antibiotics, sepsis-related mortality increases by 7.6%. Furthermore, compliance with sepsis bundles has demonstrated remarkable benefits, with the International Multicentre Prevalence Study finding a 40% reduction in hospital mortality with 3-hour bundle compliance and a 36% reduction with 6-hour bundle compliance.

The disparity between these two approaches extends beyond clinical considerations to financial implications as well. The difference in reimbursement between a sepsis DRG and a simple infection DRG averages approximately $4,000 per case. This article examines the key differences between Sepsis-3 and CMS core measures, analyzes their impact on patient care, and provides guidance on navigating these competing standards in contemporary clinical practice.

Defining Sepsis: Sepsis-3 vs CMS SEP-1

The clinical understanding of sepsis has evolved substantially, yet healthcare institutions currently navigate between two distinct frameworks. This dichotomy creates both practical and regulatory challenges for clinicians at the bedside.

Sepsis-3 Criteria: SOFA and qSOFA Explained

Developed in 2016, Sepsis-3 defines sepsis as “life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection” [1]. This definition abandoned the SIRS-based approach, instead emphasizing organ dysfunction as the critical element. The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score serves as the primary diagnostic tool, with an acute increase of ≥2 points indicating organ dysfunction with mortality exceeding 10% [2]. Additionally, for rapid bedside assessment outside the ICU, clinicians can utilize the quick SOFA (qSOFA), which consists of three simple criteria: respiratory rate ≥22/min, altered mental status, and systolic blood pressure ≤100 mmHg [3]. When validated, the SOFA score demonstrated remarkable discriminative ability in predicting sepsis (AUC=0.89) [1].

CMS SEP-1 Criteria: SIRS and Organ Dysfunction

Despite advances in sepsis understanding, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) SEP-1 core measures still utilize the older Sepsis-2 framework. This approach defines sepsis as suspected infection plus ≥2 SIRS criteria (temperature >38°C or <36°C, heart rate >90, respiratory rate >20 or PaCO2<32mm Hg, WBC >12,000/mm³ or <4,000/mm³) [4]. Moreover, severe sepsis is recognized when sepsis occurs alongside organ dysfunction. In contrast, septic shock can be diagnosed with hypotension that does not respond to fluids or lactate levels ≥4 mmol/L, even in the absence of vasopressor requirements [5].

Why Definitions Matter in Clinical Practice

The conceptual disparity among these definitions engenders substantial clinical ramifications. In general, the SEP-1 criteria find a wider group of patients because many non-septic conditions can cause SIRS [6]. As a result, this could lead to unnecessary procedures, more exposure to antibiotics, and possibly higher costs due to more care being needed [6]. Meanwhile, although Sepsis-3 aims for greater specificity in identifying patients at higher mortality risk, some clinicians worry this approach might miss opportunities for early intervention [7]. This disconnect between regulatory requirements and current clinical knowledge puts a lot of mental strain on healthcare professionals who have to meet quality standards while also providing care based on evidence [6].

Compliance and Implementation Challenges

Implementing sepsis protocols presents formidable challenges for healthcare facilities striving to meet both clinical and regulatory expectations. These challenges span multiple operational domains requiring careful coordination.

Time Zero: Hospital Presentation vs Criteria Fulfillment

The determination of “time zero”—when the sepsis clock officially starts—remains one of the most contentious aspects of sepsis management protocols. Studies reveal that patients met SIRS criteria a median of 38 minutes after triage, with only 14.4% meeting two SIRS criteria at initial presentation [8]. Time zero can be defined as either triage time in emergency departments or documentation time for hospital-onset cases, typically ascertained retrospectively by chart abstractors [9]. This retrospective designation creates a disconnect between real-time clinical decision-making and later compliance evaluation. Notably, patients met shock criteria (SBP<90 and/or lactate≥4) a median of 54 minutes post-triage [8], further complicating timely intervention efforts.

Sepsis Bundle Compliance: All-or-Nothing vs Granular Tracking

The CMS SEP-1 measure utilizes an all-or-nothing approach to bundle compliance [10], which fails to capture nuanced improvements in specific care elements. Research indicates average bundle compliance rates of approximately 50-58.8% across institutions [9][11], substantially below the target benchmark of 75% [11]. The most common reasons for bundle failure include inadequate fluid administration (30 mL/kg within 3 hours), missed repeat lactate measurements, and delayed antibiotic administration [12]. Particularly concerning, hospital-presenting sepsis patients received timely antibiotics half as often as emergency department cases [13].

Electronic Medical Record (EMR) Integration and Alerts

Modern EMRs offer substantial opportunities for improving sepsis recognition through automated alerts. Implementation of sepsis alert systems has been associated with shorter time intervals from recognition to bundle implementation [14]. Advanced systems like Epic’s Sepsis Model utilize approximately 80 data elements to assess sepsis risk [15], yet require careful calibration to minimize false-positive alerts that contribute to alarm fatigue. Research demonstrates that automation of time zero has improved the performance of sepsis alerts, allowing earlier identification and intervention [9].

Staff Education and Documentation Burden

Effective sepsis programs require substantial educational investments. Hospitals implementing successful programs provide sepsis-specific training during onboarding and annual education for clinical staff [16]. Nevertheless, maintaining consistent stakeholder engagement remains challenging amid competing clinical demands and staffing shortages [11]. Ethnographic studies reveal that seemingly simple sepsis bundles “involve a complex trajectory comprising multiple interdependent tasks that require prioritization and scheduling” [1], creating substantial documentation burdens. Institutions have found that incorporating active learning strategies into sepsis education yields better long-term outcomes than traditional didactic approaches [3].

Impact on Patient Outcomes and Hospital Metrics

The divergent definitions of sepsis profoundly impact measurable outcomes, creating complex considerations for clinical practice and hospital administration.

In-Hospital Mortality: Sepsis-3 vs CMS SEP-1

Mortality rates for sepsis patients vary considerably, with overall ICU and hospital mortality rates at 25.8% and 35.3% respectively [17]. Notably, geographic variation is substantial, from 11.9% ICU/19.3% hospital mortality in Oceania to 39.5% ICU/47.2% hospital mortality in Africa [17]. Evidence regarding the effect of SEP-1 compliance on mortality remains inconsistent. Some studies demonstrate that SEP-1 compliance correlates with reduced 30-day mortality (22.22% vs 26.28%), yielding an absolute risk reduction of 4.06% [18]. Conversely, other research indicates this protective association disappears after adjusting for patient characteristics and clinical complexity [12]. A recent systematic review found “no high- or moderate-level evidence” that SEP-1 compliance improves mortality outcomes [19].

Length of Stay and ICU Utilization

ICU length of stay is undeniably longer for sepsis patients (6 days) compared to non-septic patients (2 days) [17]. Nevertheless, the median length of stay appears shorter among SEP-1 compliant cases (5 vs 6 days) [18]. Sepsis accounts for 4.7-42.2% of global ICU utilization [20]. Yet, paradoxically, some interventions designed to improve sepsis care have actually resulted in more extended stays—one study found a 12-hour higher median ICU LOS post-intervention [4].

Sepsis Core Measures CMS: Reimbursement and Penalties

The financial stakes associated with sepsis core measures have increased dramatically. In 2023, CMS incorporated SEP-1 into the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program [21], whereby financial rewards or penalties depend entirely on where hospitals fall on the nationwide performance bell curve [21]. The baseline period runs from January 2022 through December 2022, with performance measured January through December 2024 [21]. Previously, CMS penalties for readmissions reached $528 million [22].

Case Study: Bundle Compliance Before and After SEP-1

Bundle compliance rates nationally hover around 50% [10], far below optimal targets. One hospital improvement initiative demonstrated modest improvement from 57% to 62% post-implementation [23]. Bundle failures most commonly result from inadequate fluid administration (31%), missed repeat lactate measurements (19.6%), and delayed antibiotic administration (16.5%) [12]. Notably, one pediatric study demonstrated mortality reduction from 3.4% to 1.2% concurrent with bundle compliance improvement from 30% to 62% [24].

Clinical and Operational Trade-offs

The tension between standardized protocols and clinical judgment creates substantial challenges for sepsis management. These trade-offs manifest in multiple domains of care delivery.

Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment Risks with SEP-1

Studies indicate potential overdiagnosis rates of 20-30% with SEP-1 compared to Sepsis-3 criteria [6]. The IDSA has expressed concerns about SEP-1’s potential to drive unnecessary antibiotic use, given that up to 40% of patients initially treated for sepsis subsequently demonstrate a low probability of bacterial infection [2]. Several hospitals have reported increased broad-spectrum antibiotic use and C. difficile infection rates following implementation of aggressive sepsis protocols [2]. Ironically, aggressive antibiotic prescribing in critically ill patients has occasionally been linked to higher mortality rates compared to more conservative approaches [2].

Alert Fatigue and Provider Burnout

The average ICU clinician faces more than 900 active and passive alerts daily [25]. In one hospital, switching to a commercial EHR increased alert burden six-fold yet saw acceptance rates plummet from 100% to merely 8.4% for high-severity alerts [25]. According to AHRQ, “busy workers become desensitized to safety alerts and fail to respond appropriately” [26]. One institution described its SIRS-based sepsis alert system as a “total disaster” that frustrated providers [27].

Flexibility in Sepsis-3 vs Rigidity in CMS Measures

SEP-1’s all-or-nothing approach [7] has proven problematic. Patients receiving non-compliant care often have more complex conditions, unusual presentations, or require urgent procedures [28]. Sepsis-3 criteria potentially allow for more nuanced clinical decision-making [6], enabling clinicians to tailor treatment approaches based on individual patient circumstances.

Comparison Table

| Aspect | Sepsis-3 | CMS SEP-1 |

| Definition | Life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection | Based on Sepsis-2 framework; suspected infection plus ≥2 SIRS criteria |

| Primary Diagnostic Criteria | SOFA score increase ≥2 points; qSOFA for rapid assessment (respiratory rate ≥22/min, altered mental status, SBP ≤100 mmHg) | Temperature >38°C or <36°C, heart rate >90, respiratory rate >20 or PaCO2<32mm Hg, WBC >12,000/mm³ or <4,000/mm³ |

| Diagnostic Accuracy | Higher specificity; AUC=0.89 for SOFA score | Identifies broader patient population; 20-30% potential overdiagnosis compared to Sepsis-3. |

| Clinical Flexibility | Allows more nuanced clinical decision-making | Rigid, all-or-nothing approach to bundle compliance |

| Implementation Challenges | Not mentioned specifically | Average bundle compliance rates 50-58.8%; target benchmark 75% |

| Common Compliance Issues | Not mentioned specifically | Inadequate fluid administration (30%), missed repeat lactate measurements (19.6%), delayed antibiotic administration (16.5%) |

| Financial Impact | Not mentioned specifically | ~$4,000 difference in reimbursement between sepsis DRG and simple infection DRG |

| Clinical Concerns | May miss opportunities for early intervention | Risk of overtreatment and unnecessary antibiotic exposure |

Conclusion

The ongoing tension between Sepsis-3 criteria and CMS SEP-1 core measures reflects a broader challenge in modern healthcare: balancing evidence-based practice with regulatory requirements. Healthcare organisations need to find their way through these conflicting frameworks while still keeping the focus on patient outcomes. Sepsis-3 is more specific because it uses the SOFA scale, which lowers the chances of overdiagnosis. On the other hand, SEP-1 measures use SIRS criteria to cast a wider diagnostic net. It could mean that more patients are included, but it could also mean that unnecessary treatments and antibiotic exposure happen more often.

Clinical teams face substantial operational hurdles regardless of which definition they adopt. Bundle compliance rates hover around 50-58.8%, well below the 75% benchmark. Time zero determination remains particularly problematic, with studies showing patients typically meet SIRS criteria a median of 38 minutes after triage. Furthermore, the all-or-nothing compliance approach mandated by CMS fails to recognize incremental improvements in sepsis care delivery.

Financial considerations add another layer of complexity to this clinical conundrum. The approximately $4,000 difference between sepsis DRG and simple infection DRG reimbursements creates powerful incentives that shape institutional policies. CMS’s recent incorporation of SEP-1 into the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program further elevates these stakes, tying financial outcomes directly to sepsis performance metrics.

Electronic health records present both opportunities and challenges for sepsis recognition. Though automated alert systems can expedite identification and intervention, they simultaneously contribute to the estimated 900 daily alerts facing ICU clinicians. This alert fatigue phenomenon undermines the effectiveness of even well-designed detection tools, as evidenced by the dramatic drop in acceptance rates for high-severity alerts observed in some institutions.

Healthcare organizations must therefore develop nuanced approaches that satisfy regulatory requirements while preserving clinical judgment. Rather than viewing Sepsis-3 and SEP-1 as mutually exclusive frameworks, forward-thinking institutions might consider utilizing elements from both. Sepsis-3 criteria could guide clinical decision-making at the bedside while documentation practices align with SEP-1 requirements for regulatory compliance.

The evidence presented throughout this article underscores an uncomfortable reality: neither definition system perfectly serves all stakeholders in sepsis care. Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations that must be weighed against institutional priorities and patient populations. Until consensus emerges between clinical and regulatory standards, clinicians must remain vigilant about sepsis recognition while exercising appropriate judgment regarding bundle implementation.

In the end, timely intervention is still the most important thing, no matter how you define it. The 7.6% rise in deaths for every hour without antibiotics is a clear reminder that definitions and metrics are essential, but taking action quickly saves lives. Healthcare systems would benefit from concentrating on the development of efficient workflows that facilitate the swift identification and treatment of potentially septic patients, while reducing unnecessary interventions for those unlikely to gain from aggressive sepsis protocols.

Key Takeaways

Healthcare providers face a critical choice between two sepsis frameworks that significantly impact patient care, compliance metrics, and financial outcomes.

- Sepsis-3 offers higher diagnostic accuracy with SOFA scores (AUC=0.89) but may miss early intervention opportunities, while CMS SEP-1 casts a broader net with 20-30% potential overdiagnosis rates.

- Bundle compliance remains challenging with national rates at only 50-58.8% versus the 75% target, primarily due to inadequate fluid administration and delayed antibiotic delivery.

- Financial stakes are substantial with approximately $4,000 reimbursement difference between sepsis and infection DRGs, plus CMS penalties now tied to Hospital Value-Based Purchasing programs.

- Alert fatigue undermines sepsis detection as ICU clinicians face over 900 daily alerts, causing acceptance rates to plummet from 100% to just 8.4% for high-severity warnings.

- Time remains critical regardless of definition since mortality increases 7.6% for every hour without antibiotics, making rapid recognition and intervention paramount over perfect compliance.

The key is developing workflows that balance regulatory requirements with clinical judgment, utilizing elements from both frameworks to optimize patient outcomes while meeting institutional metrics.

Frequently Asked Questions:

FAQs

Q1. What is the main difference between Sepsis-3 and CMS SEP-1 criteria? Sepsis-3 defines sepsis as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection, using SOFA scores for diagnosis. CMS SEP-1 uses the older Sepsis-2 framework, defining sepsis as suspected infection plus at least two SIRS criteria.

Q2. How does bundle compliance impact sepsis management? Bundle compliance rates nationally average around 50-58.8%, below the target of 75%. Improved compliance has been associated with reduced mortality in some studies, but challenges remain in areas like fluid administration, repeat lactate measurements, and timely antibiotic delivery.

Q3. What are the financial implications of sepsis management for hospitals? There’s approximately a $4,000 difference in reimbursement between the sepsis DRG and the simple infection DRG. Additionally, CMS has incorporated SEP-1 into the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program, tying financial rewards or penalties to sepsis performance metrics.

Q4. How does alert fatigue affect sepsis detection in hospitals? Alert fatigue is a significant challenge, with ICU clinicians facing over 900 alerts daily. It can lead to desensitization and reduced response to safety alerts, potentially compromising timely sepsis detection and intervention.

Q5. Why is timely intervention crucial in sepsis management, regardless of the definition used? Regardless of the sepsis definition used, prompt intervention is critical because mortality increases by 7.6% for every hour without antibiotics. It emphasizes the importance of rapid recognition and treatment initiation for potentially septic patients.

References:

[1] – https://www.cdc.gov/sepsis/hcp/core-elements/index.html

[2] – https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/72/4/541/5831166

[3] – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195670122000093

[4] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10113981/

[5] – https://foamed.ebmedicine.net/rapid-reference/sepsis-and-cms/

[6] – https://pearlhealth.com/blog/healthcare-insights/evolving-cms-definition-of-sepsis/

[7] – https://www.cms.gov/files/document/patientsafetysepsistepsumm-508.pdf

[8] – https://www.annemergmed.com/article/S0196-0644(13)01065-2/fulltext

[9] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6789198/

[10] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6588513/

[11] – https://www.clinicaladvisor.com/features/improving-sepsis-bundle-compliance/

[12] – https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2831700

[13] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6625440/

[14] – https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2821277

[15] – https://journals.lww.com/ccejournal/fulltext/2023/07000/epic_sepsis_

model_inpatient_predictive_analytic.8.aspx

[16] – https://www.cdc.gov/sepsis/hcp/core-elements/assessment-tool.html

[17] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6289022/

[18] – https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(21)03623-0/fulltext

[20] – https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2024.1473533/full

[21] – https://blog.medisolv.com/articles/cms-sepsis-measures-hvbp

[22] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5482234/

[23] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9448659/

[25] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7442505/

[28] – https://medicalxpress.com/news/2025-03-effectiveness-sepsis-quality-patient-outcomes.html