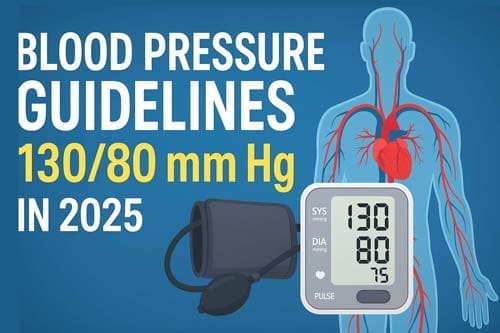

New Blood Pressure Guidelines: Why 130/80 mm Hg Sparks Fresh Debate in 2025

Introduction

The prevalence of high blood pressure is expected to triple among men under age 45 and double among women under 45 with new blood pressure guidelines redefining hypertension as readings of 130/80 mm Hg or higher. This major shift represents one of the most consequential changes in cardiovascular risk assessment in recent years. Hypertension stands as a leading risk factor for cardiovascular disease globally, ranking first in disability-adjusted life years in the United States and worldwide.

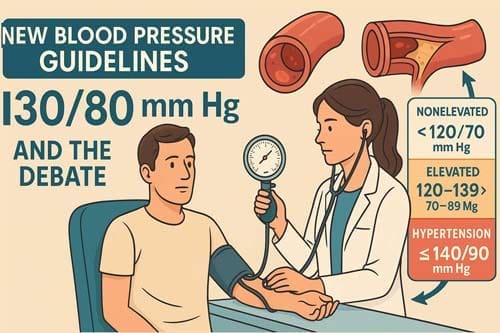

The evolution of hypertension guidelines has sparked considerable debate among practitioners. Since the 2017 ACC/AHA blood pressure guidelines first redefined hypertension as BP ≥130/80 mmHg, clinicians have grappled with implementing these lower thresholds in diverse patient populations. The latest hypertension guidelines in 2024 introduced further refinements, including a new blood pressure categorization system that distinguishes between nonelevated (<120/70 mm Hg), elevated (120–139/70–89 mm Hg), and hypertension (≥140/90 mm Hg). However, treatment recommendations continue to target blood pressure levels below 130/80 mm Hg for many high-risk patients.

This article examines the rationale behind the 130/80 mm Hg threshold, compares current guidelines with previous recommendations, and analyzes the clinical implications of these changes. While the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) provided compelling evidence for intensive treatment approaches, questions remain about potential overdiagnosis and implementation challenges in primary care settings. Furthermore, the article explores how these guidelines account for special populations, including adults aged 85 and older or those with frailty, where modified targets may be more appropriate.

Why 130/80 mm Hg Is the New Threshold in 2025

The 2025 hypertension guidelines introduce an important evolution in how elevated blood pressure is managed. While the official diagnostic definition of hypertension remains at 140/90 mm Hg, the new threshold of 130/80 mm Hg now serves as a key marker for initiating treatment in high-risk individuals. This reflects a growing emphasis on early intervention and risk-based care, aiming to prevent long-term cardiovascular complications before they arise.

Comparison with 2017 ACC/AHA and 2023 ESH Guidelines

In 2017, the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) made a landmark decision to lower the diagnostic cutoff for hypertension from 140/90 mm Hg to 130/80 mm Hg. [1] This change was based on robust evidence that even modest elevations in blood pressure can increase the risk of heart disease, stroke, and kidney damage.

However, the 2023 European Society of Hypertension (ESH) guidelines maintained the traditional threshold of 140/90 mm Hg for diagnosing hypertension. The ESH acknowledged the increased risk at lower levels but preferred to reserve the diagnosis of hypertension for more sustained and notable elevations in blood pressure. This divergence in recommendations led to some uncertainty in clinical practice [2].

The 2025 guidelines show a middle-ground approach, with a more nuanced categorization system:

- Nonelevated: <120/70 mm Hg

- Elevated: 120–139/70–89 mm Hg

- Hypertension: ≥140/90 mm Hg [3]

Although the diagnostic definition of hypertension remains unchanged, the 2025 update introduces a treatment threshold of 130/80 mm Hg for individuals considered to be at increased cardiovascular risk. This includes patients with:

- Established cardiovascular disease

- Diabetes mellitus

- Chronic kidney disease

- A high calculated 10-year cardiovascular risk

This means that while a patient may not be diagnosed with hypertension until they reach 140/90 mm Hg, clinicians are now encouraged to start pharmacological treatment and lifestyle interventions at 130/80 mm Hg in those with high-risk profiles [4].

Rationale Behind Lowering the Diagnostic Cutoff

The evidence supporting the 130/80 mm Hg threshold comes primarily from clinical trials demonstrating cardiovascular benefit with lower targets. The SPRINT trial showed that targeting systolic blood pressure below 120 mm Hg reduced the risk of heart attacks, heart failure, and stroke compared to traditional targets [5]. A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted for the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines found that lowering systolic blood pressure to <130 mm Hg reduced the risk of major cardiovascular events (relative risk 0.84) and stroke (relative risk 0.82) [6].

Nevertheless, several meta-analyzes have presented conflicting evidence. A study-level analysis excluding treat-to-target trials found no cardiovascular benefit in primary prevention when lowering systolic BP in the 130-140 mm Hg range, though secondary prevention showed modest benefits [6]. The 2025 guidelines acknowledge this evidence dichotomy, adopting the SCORE2 and SCORE2-OP risk prediction models to better identify patients most likely to benefit from treatment at lower thresholds [2].

Impact on Hypertension Prevalence Rates

Adopting a 130/80 mm Hg threshold significantly increases the statistical prevalence of hypertension. Under the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines, the estimated prevalence of hypertension among US adults rose to 44.0% compared to 34.2% using traditional thresholds [1]. This reveals an absolute increase of 9.8% and a relative increase of 28.6% [1].

The demographic impact of this change is not uniform. The absolute increase in hypertension prevalence was largest for:

- Adults aged 40-59 years

- Men

- Individuals with obesity

- People without significant comorbidities like diabetes or cardiovascular disease [1]

Individuals reclassified as having hypertension under the lower threshold are typically younger, less likely to have diabetes mellitus or cardiovascular disease, and have a lower estimated 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk compared to those classified as hypertensive under traditional thresholds [1].

Implementation of these thresholds in clinical practice has faced challenges. Despite the 2017 guidelines, a CDC analysis found that self-reported diagnoses of hypertension did not change significantly between 2017 and 2021 [7]. Several factors potentially contributed to this gap, including slow guideline adoption, conflicting performance measures, and disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic [7].

The 2025 guidelines attempt to address these implementation challenges by providing clearer risk-based treatment algorithms and out-of-office monitoring recommendations as a Class I recommendation [3].

Updated Blood Pressure Classifications in 2025 Guidelines

The 2025 guidelines establish a simplified yet more precise blood pressure classification system, addressing limitations in previous frameworks. This revised approach aims to facilitate earlier identification of at-risk individuals and improve clinical decision-making in hypertension management.

Nonelevated: <120/70 mm Hg

The 2025 guidelines introduce “nonelevated” as the lowest blood pressure category, defined as readings below 120/70 mm Hg [8]. This category reveals optimal cardiovascular health, replacing what was previously termed “normal” in earlier classification systems. At this level, pharmacological treatment is not recommended [8]. This classification acknowledges recent evidence suggesting that even readings traditionally considered normal may confer some cardiovascular risk if they approach the upper limits of normal ranges. Notably, this threshold is lower than the <120/80 mm Hg that defined normal blood pressure in previous guidelines [9]. The adjustment reflects mounting evidence that cardiovascular benefits extend into lower blood pressure ranges, particularly among younger adults. Additionally, this category serves as a clear target for lifestyle interventions in primary prevention settings.

Elevated: 120–139/70–89 mm Hg

Perhaps the most important change in the 2025 guidelines is the expanded “elevated” blood pressure category, encompassing readings from 120–139/70–89 mm Hg [8]. This range consolidates what were previously multiple categories, including “elevated,” “high-normal,” and “Stage 1 hypertension” in various prior guidelines [10]. The 2025 guidelines specify that drug treatment may be recommended within this category based on cardiovascular disease risk assessment and follow-up blood pressure levels [8]. According to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), this new category was created to “facilitate consideration of more intensive blood pressure treatment targets among persons at increased risk for cardiovascular disease” [11]. Essentially, this classification acknowledges that “people do not go from normal BP to hypertensive overnight” but rather experience “a steady gradient of change” [11].

Hypertension: ≥140/90 mm Hg

The 2025 guidelines maintain the traditional definition of hypertension as blood pressure readings at or above 140/90 mm Hg [8]. For patients in this category, prompt confirmation and drug treatment are recommended in most individuals [8]. This approach differs from the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines, which had lowered the hypertension threshold to ≥130/80 mm Hg [12]. Instead, the 2025 guidelines align more closely with the European Society of Hypertension’s (ESH) position while still emphasizing aggressive treatment for high-risk patients. The 2025 guidelines justify maintaining this threshold because “this is the BP threshold above which treatment to lower BP results in net benefit for almost all adults” [8].

Stage 1 vs Stage 2: Revisions in Terminology

The 2025 guidelines mark a departure from the staging terminology used in previous classification systems. Prior to these updates, the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines classified Stage 1 hypertension as 130–139/80–89 mm Hg and Stage 2 as ≥140/90 mm Hg [10]. The term “prehypertension” has been completely eliminated from current guidelines, having been deemed “too vague” and failing to “clearly signal the need for intervention” [13]. Moreover, the 2023 ESH guidelines had proposed an alternative staging system based not just on blood pressure values but also on complications: Stage 1 (uncomplicated hypertension), Stage 2 (presence of hypertension-mediated organ damage, diabetes, or chronic kidney disease stage 3), and Stage 3 (presence of cardiovascular disease or advanced kidney disease) [8]. The 2025 guidelines opted for a simpler classification system focused primarily on blood pressure values rather than this complications-based staging, thereby prioritizing clinical utility and ease of implementation in diverse healthcare settings.

Diagnostic and Monitoring Recommendations

Accurate diagnosis remains the cornerstone of effective hypertension management, with the 2025 guidelines emphasizing the critical role of proper measurement techniques and monitoring protocols. These recommendations reflect substantial advancements in our understanding of blood pressure variability and measurement methodology.

Out-of-Office BP Monitoring as Class I Recommendation

The 2025 guidelines designate out-of-office blood pressure monitoring as a Class I recommendation for confirming hypertension diagnosis and guiding treatment decisions. This elevated status acknowledges compelling evidence that out-of-office measurements correlate more strongly with cardiovascular outcomes than clinic readings [14]. Multiple guidelines concur on this approach, with the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines first designating out-of-office monitoring as a Class IA recommendation [5]. This consensus stems from research demonstrating that out-of-office readings provide superior prognostic information about cardiovascular risk and mortality [5]. Furthermore, this approach effectively identifies white coat hypertension (present in 9-23% of the general population) and masked hypertension (affecting 6.7-20% of individuals) [5].

Ambulatory vs Home BP Monitoring: When to Use Each

Both ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) and home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) serve important roles, though they differ in application. ABPM remains the preferred method for initial diagnosis among individuals not taking antihypertensive medications [3]. It captures 40-60 measurements over 24 hours, requires no human interaction beyond keeping still, measures BP under varied conditions, and uniquely provides nocturnal readings [15]. Conversely, HBPM shows the preferred approach for individuals already on antihypertensive therapy [3]. This method involves self-measurement using validated devices, typically twice daily for 3-7 days [16]. HBPM offers greater accessibility and tolerability, with approximately 21.7% of US adults reporting its use in the past year [3]. Consequently, clinicians should consider both methods complementary rather than competitive, selecting based on clinical context and patient factors.

Cuffless Devices: Not Recommended in Clinical Practice

Despite technological advancements, the 2025 guidelines explicitly advise against using cuffless blood pressure devices for clinical decision-making. These devices employ various methodologies including pulse arrival time, pulse transit time, and pulse wave analysis [17]. Although they offer convenience and continuous monitoring capabilities, fundamental concerns about accuracy persist [18]. Current validation standards for cuffless technologies remain inadequate, with particular issues regarding individual calibration requirements, measurement stability, and ability to track BP changes [18]. Therefore, until robust validation protocols are established and implemented, clinicians and patients should exclusively use validated cuff-based devices [19]. Indeed, focusing on establishing robust validation standards shows a critical priority for advancing this promising yet currently unreliable technology [20].

Treatment Thresholds and Targets in the Latest Guidelines

The 2025 hypertension guidelines offer a more refined, risk-based approach to initiating and targeting blood pressure treatment. These updates prioritize individualized care while incorporating the latest evidence on cardiovascular risk and treatment outcomes.

When to Start Drug Therapy at 130/80 mm Hg

Pharmacological therapy should begin at a blood pressure of 130/80 mm Hg in adults with established hypertension and:

- Clinical cardiovascular disease (CVD), or

- A 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk of 10% or higher [21].

This threshold also applies to primary prevention in individuals with:

- An estimated 10-year ASCVD risk of 10% or more, and

- Systolic BP of 130 mm Hg or higher or diastolic BP of 80 mm Hg or higher [22].

In patients with CVD, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, or diabetes, drug therapy is indicated if BP remains at 130–139/80–89 mm Hg after three months of lifestyle modification [8].

SCORE2 and SCORE2-OP for Risk-Based Treatment

The 2025 guidelines officially adopt the Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation 2 (SCORE2) tool for cardiovascular risk stratification [2]. Unlike earlier risk calculators, SCORE2 estimates both fatal and nonfatal CVD events in adults aged 40-69 years [2]. For older individuals, the guidelines uniquely recommend SCORE2-Older Persons (SCORE2-OP), specifically designed for adults ≥70 years [2]. Together, these tools inform treatment decisions, with SCORE2/SCORE2-OP 10-year CVD risk ≥10% representing a key threshold for initiating therapy at 130/80 mm Hg [8].

Default SBP Target: 120–129 mm Hg if Tolerated

For most patients, the guidelines recommend a default systolic blood pressure target of 120-129 mm Hg if tolerated [8]. This recommendation draws from the SPRINT trial, which demonstrated a 27% lower hazard for primary cardiovascular outcomes and 25% reduced mortality with intensive treatment targeting SBP <120 mm Hg [4]. Importantly, if standard targets prove intolerable due to side effects, the guidelines advise aiming for SBP levels “as low as reasonably achievable” [8].

Exceptions for Frail Adults and Those ≥85 Years

The guidelines acknowledge that not all patients benefit from aggressive blood pressure lowering. Hence, a more lenient target (BP <140/90 mm Hg) should be considered for individuals with symptomatic orthostatic hypotension or age ≥85 years [8]. Similarly, this relaxed target may be appropriate for moderately-to-severely frail individuals or those with limited life expectancy [8]. Several observational studies support this approach, showing that systolic BP <130 mm Hg in frail elderly patients correlates with higher morbidity and mortality [23].

Controversies and Clinical Implications of the 130/80 Debate

Medical debate surrounding the 130/80 mm Hg threshold continues to unfold as clinicians weigh potential benefits against practical concerns across diverse healthcare settings.

Concerns About Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment

Adopting a 130/80 mm Hg threshold substantially increases hypertension prevalence—to approximately 46% of the adult population [24]. This expansion primarily affects individuals with 10-year cardiovascular risk below 10%, who may gain minimal benefit yet face potential harms [25]. Measurement variability near population averages exacerbates this issue; studies estimate 65-72% of people with true systolic BP between 120-129 mm Hg could be overdiagnosed after five sets of measurements using ACC/AHA criteria [26]. Beyond psychological impacts of disease labeling, patients may face financial consequences when declaring a “pre-existing condition” to insurance companies [25].

SPRINT vs Cochrane Review: Conflicting Evidence

The SPRINT trial initially bolstered support for intensive treatment, yet methodological limitations including its open-label design and premature truncation may have exaggerated benefits [6]. In contrast, the 2018 Cochrane Review—the only individual participant-level meta-analysis available—concluded no net health benefit occurs from targets below 135/85 mm Hg [6]. Absolute risk reductions remain modest: 0.5% for stroke and 1.1% for major adverse cardiovascular events with intensive BP lowering [6]. This disparity explains why most national guidelines outside the 2017 ACC/AHA maintain the traditional 140/90 mm Hg threshold [6].

Implementation Challenges in Primary Care Settings

Clinical application faces obstacles including time constraints during consultations, electronic medical record limitations, and physician concerns about medication side effects [27]. Primary care physicians report difficulty managing BP phenotypes like masked and isolated diastolic hypertension [27]. Many practitioners remain reluctant to initiate dual therapy even when guidelines recommend it [27].

Global Variability in Hypertension Guidelines

Guidelines developed in high-income countries often fail to account for resource limitations elsewhere [28]. Implementing lower thresholds in low-middle income countries could divert scarce resources from existing hypertension management [28]. Among Asian countries—where control rates already lag, adopting 130/80 mm Hg would markedly increase uncontrolled hypertension prevalence [29]. Accordingly, 87% of Asian physicians recognize the need for region-specific guidelines reflecting ethnic differences and healthcare infrastructure [29].

Conclusion

The shifting landscape of hypertension management reflects an evolving understanding of cardiovascular risk assessment. Through redefined thresholds and classification systems, clinicians now face both opportunities and challenges when interpreting the 130/80 mm Hg debate. This tension between aggressive treatment and cautious approaches continues to shape clinical practice worldwide.

Evidence supporting lower thresholds primarily stems from randomized trials showing cardiovascular benefits, yet concerns about overdiagnosis remain valid. The three-tiered classification system—nonelevated, elevated, and hypertension—offers a practical framework while acknowledging blood pressure as a continuous risk factor rather than a binary condition. Nevertheless, treatment decisions require nuanced clinical judgment beyond simple numeric cutoffs.

The elevation of out-of-office monitoring to a Class I recommendation demonstrates a major advancement in diagnostic accuracy. Ambulatory and home monitoring now serve complementary roles, though cuffless technologies still lack sufficient validation for clinical use. These measurement approaches help identify white coat and masked hypertension, conditions that would otherwise confound treatment decisions.

Risk stratification tools such as SCORE2 and SCORE2-OP allow clinicians to tailor treatment decisions to individual patient profiles. The default target of 120-129 mm Hg appears reasonable for most patients, though exceptions exist for frail adults and those aged 85 years or older. This personalized approach balances cardiovascular protection against potential treatment burdens.

Primary care practitioners face implementation hurdles ranging from time constraints to electronic medical record limitations. Therefore, successful adoption requires systems-level changes rather than merely disseminating new thresholds. Additionally, global variability in resources necessitates contextual adaptation of these guidelines across different healthcare settings.

While the debate continues, prudent clinicians must stay informed about evolving evidence while applying these guidelines thoughtfully to individual patients. The 130/80 mm Hg threshold will undoubtedly spark further research and refinement of approaches. Ultimately, these guidelines should serve as tools to improve patient outcomes rather than rigid protocols that override clinical judgment. Both research and clinical experience will continue to shape hypertension management strategies as new evidence emerges in the years ahead.

Key Takeaways

The 2025 blood pressure guidelines introduce marked changes that will reshape hypertension diagnosis and treatment, affecting millions of patients worldwide.

- New 130/80 threshold triples hypertension rates in men under 45 and doubles rates in women under 45, dramatically expanding the population requiring treatment consideration.

- Three-tier classification system simplifies diagnosis: Nonelevated (<120/70), Elevated (120-139/70-89), and Hypertension (≥140/90) replaces complex staging terminology.

- Out-of-office monitoring becomes mandatory as Class I recommendation, with ambulatory monitoring preferred for initial diagnosis and home monitoring for treatment follow-up.

- Risk-based treatment using SCORE2 tools determines when to start medication at 130/80, targeting patients with ≥10% 10-year cardiovascular disease risk.

- Default blood pressure target drops to 120-129 mmHg for most patients, with exceptions for frail adults and those ≥85 years who may need less aggressive targets.

- Implementation faces major challenges including concerns about overdiagnosis, conflicting evidence from major trials, and practical barriers in primary care settings.

The guidelines represent a middle-ground approach between aggressive American standards and conservative European thresholds, emphasizing personalized care while acknowledging ongoing scientific debate about optimal blood pressure management.

Frequently Asked Questions:

FAQs

Q1. What are the key changes in the 2025 blood pressure guidelines? The 2025 guidelines introduce a new three-tier classification system: nonelevated (<120/70 mm Hg), elevated (120-139/70-89 mm Hg), and hypertension (≥140/90 mm Hg). They also recommend initiating treatment at 130/80 mm Hg for high-risk individuals and emphasize out-of-office blood pressure monitoring.

Q2. How does the new 130/80 mm Hg threshold impact hypertension diagnosis? The 130/80 mm Hg threshold increases hypertension prevalence, potentially tripling rates in men under 45 and doubling rates in women under 45. This change expands the population requiring treatment consideration, particularly affecting younger adults and those without critical comorbidities.

Q3. What is the recommended blood pressure target for most patients? For most patients, the guidelines recommend a default systolic blood pressure target of 120-129 mm Hg, if tolerated. However, for frail adults and those aged 85 years or older, a more lenient target of <140/90 mm Hg may be appropriate.

Q4. How do the new guidelines address out-of-office blood pressure monitoring? Out-of-office blood pressure monitoring is now a Class I recommendation for confirming hypertension diagnosis and guiding treatment decisions. Ambulatory monitoring is preferred for initial diagnosis, while home monitoring is recommended for treatment follow-up.

Q5. What challenges do healthcare providers face in implementing these new guidelines? Healthcare providers face several implementation challenges, including time constraints during consultations, electronic medical record limitations, and concerns about medication side effects. There are also ongoing debates about potential overdiagnosis and overtreatment, particularly in low-risk individuals.

References:

[1] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6205214/

[2] – https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/Articles/2024/02/05/11/43/2023-ESH-Hypertension-Guideline-Update

[3] – https://www.nature.com/articles/s41440-022-01137-2

[4] – https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/Articles/2021/11/11/13/58/Guidance-on-Approaching-HTN-in-Patients-Over-80-Years-of-Age

[5] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6974752/

[6] – https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.14647

[7] – https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/73/wr/mm7309a1.htm

[8] – https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.124.24173

[9] – https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diagnostics/17649-blood-pressure

[10] – https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/understanding-blood-pressure-readings

[11] – https://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/Press-Office/Press-releases/New-ESC-Hypertension-Guidelines-recommend-intensified-BP-targets-and-introduce-a-novel-elevated-blood-pressure-category-to-better-identify-people-at-risk-for-heart-attack-and-stroke

[12] – https://www.health.harvard.edu/heart-health/reading-the-new-blood-pressure-guidelines

[13] – https://cvhealthclinic.com/news/the-updated-guidelines-for-high-blood-pressure/

[14] – https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/hypertension/how-policy-changes-clear-path-out-office-bp-monitoring

[15] – https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.14650

[16] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11857694/

[17] – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666693623000014

[18] – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35708294/

[19] – https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamacardiology/article-abstract/2832857

[20] – https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.125.24822?doi=10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.125.24822

[21] – https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/ten-points-to-remember/2017/11/09/11/41/2017-Guideline-for-High-Blood-Pressure-in-Adults

[22] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5879505/

[23] – https://journals.lww.com/jhypertension/fulltext/2023/

“10000/antihypertensive_treatment_in_people_of_very_old.2.aspx

[24] – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30979699/

[25] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7810411/

[26] – https://journals.lww.com/jhypertension/fulltext/2021/02000/

the_potential_for_overdiagnosis_and_underdiagnosis.7.aspx

[27] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11526237/

[28] – https://www.bmj.com/content/365/bmj.l1657/rr-0

[29] – https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/hypertensionaha.118.11203