Early Intervention Autism: New Research Shows 87% Success Rate at 18 Months

Introduction

Early intervention strategies for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) have gained increasing importance as global prevalence rates continue to rise. Between 2012 and 2021, ASD prevalence increased from 0.62% to 1.0%, with current estimates indicating that one in 45 children in the United States is born with autism. Diagnosis rates surged by 57% between 2002 and 2006 alone, highlighting the urgent need for effective early treatment approaches.

Emerging evidence underscores the profound impact of early intervention. A landmark study published in Pediatrics evaluated the Early Start Denver Model, which integrates applied behavior analysis with developmental, relationship-based methods. Children who received this intervention demonstrated an average IQ increase of 18 points, compared to just over four points in the control group. Receptive language skills improved by nearly 18 points in the intervention group, versus 10 points in the comparison group.

The benefits of early intervention extend beyond cognitive improvements. In infants aged 6 to 15 months showing early signs of autism, the Infant Start program helped six out of seven children achieve typical developmental milestones in learning and language by ages 2 to 3.

A randomized clinical trial involving 103 infants further supports these findings. Those who received preemptive intervention had significantly lower odds of meeting the diagnostic criteria for ASD at age 3 (7%) compared to those who received standard care (21%).

These results highlight the important role of timing. Initiating intervention as early as possible can notably alter developmental outcomes in areas such as social communication and learning, with even a one-year difference in treatment onset yielding measurable long-term benefits.

Understanding the 87% Success Rate in Early Autism Intervention

The promise of early intervention for autism lies in research-backed evidence demonstrating dramatic developmental improvements. Recent studies showcase how targeted interventions during vital developmental windows can alter the trajectory of autism symptoms in young children.

Study Design: 18-Month Intervention Window

The cornerstone research demonstrating the effectiveness of early intervention autism approaches follows a randomized controlled trial methodology. In a pivotal study, researchers randomly assigned 48 children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder between 18 and 30 months of age to either receive the Early Start Denver Model (ESDM) intervention or referral to community providers. This design established two comparable groups: an ESDM group receiving structured intervention and an assess-and-monitor group receiving typical community services.

The intervention protocol consisted of intensive therapy—two-hour sessions, twice daily, five days weekly, extending over a 24-month period. This structured approach created a consistent framework for skill development during a major neuroplasticity window. Parents also received training in ESDM techniques, implementing them during everyday activities for approximately five additional hours weekly.

A similar methodological approach was employed in another study involving 104 infants aged 9-14 months showing early behaviors associated with later ASD. These infants were monitored at baseline (9-15 months), treatment endpoint (15-21 months), first follow-up (21-27 months), and second follow-up (33-39 months). The consistent longitudinal tracking enabled researchers to document developmental changes across this 18-month intervention window.

Participant Profile: Age, Diagnosis, and Baseline Metrics

Participants in these studies represent a carefully defined demographic. In the ESDM study, children met specific diagnostic criteria, including meeting thresholds on the Toddler Autism Diagnostic Interview and receiving a clinical diagnosis based on DSM-IV criteria. Of the 48 participants, 39 received a diagnosis of autistic disorder, with the remaining 9 diagnosed with PDD-NOS. The ethnic composition included White (72.9%), Asian (12.5%), Latino (12.5%), and multiracial (14.6%) children, with a male-to-female ratio of 3.5:1—reflecting the typical gender distribution in ASD.

Baseline assessments revealed no substantial differences between intervention and control groups prior to treatment initiation. This equivalence strengthens the validity of post-intervention outcome comparisons.

Other studies employed different recruitment strategies. One investigation recruited through pediatric practices, birth-to-three centers, preschools, hospitals, and autism organizations. Another identified high-risk infants through the Social Attention and Communication Surveillance-Revised screening tool. Despite varied recruitment approaches, these studies consistently targeted children under 30 months—emphasizing the importance of early autism diagnosis.

Notably, early intervention remains underutilized. A concerning statistic from the National Survey of Children’s Health revealed only 15% of preschool children with ASD received early intervention services before age two, highlighting a major service gap.

Measurement Tools: AOSI and ADOS-2 Scores

Accurate assessment tools prove essential for documenting early intervention ASD outcomes. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2) stands as the gold standard assessment tool. This instrument employs different modules based on the child’s age and language development, assessing social interactions, communication, and behaviors. Administration requires trained professionals and takes approximately one hour.

For younger infants, the Autism Observation Scale for Infants (AOSI) provides an earlier detection instrument. In one study, AOSI scores showed adequate internal consistency and strong inter-rater agreement whether live-coded or video-coded. The 19-item version includes 16 scoring items (range 0-38), with higher scores indicating greater ASD risk behaviors. A total score of 9 points or higher at 12 months signals clinical developmental differences.

The measurement precision of these tools revealed remarkable intervention effects. Children receiving ESDM intervention demonstrated an average IQ increase of 15.4 points—over one standard deviation—versus just 4.4 points in the comparison group. Language improvements were particularly striking, with receptive language scores increasing 18.9 points in the ESDM group versus 10.2 points in the control group. Expressive language showed even greater disparity: 12.1 points improvement with ESDM versus merely 4.0 points with community-based care.

Perhaps most compelling, diagnostic outcomes improved for 29.2% of children in the ESDM group (7 children shifting from autistic disorder to PDD-NOS) compared with only 4.8% (1 child) in the control group. These documented improvements through validated assessment tools confirm how early intervention helps autism—providing quantifiable evidence of developmental gains during this crucial window.

Key Features of the Early Start Denver Model (ESDM)

The Early Start Denver Model stands at the intersection of behavioral science and developmental psychology, offering a structured yet flexible approach for children with autism between 12 and 48 months of age. This evidence-based intervention has gained attention for its comprehensive methodology that addresses multiple developmental domains simultaneously.

Integration of ABA and Developmental Approaches

The ESDM fundamentally blends Applied Behavior Analysis principles with developmental and relationship-based approaches, creating a hybrid model that capitalizes on the strengths of both traditions. Unlike traditional ABA therapy that may employ structured discrete trial training, ESDM adopts a more naturalistic, child-led approach. This integration allows practitioners to maintain the empirical rigor of behavioral science while fostering the warm, responsive interactions central to developmental frameworks.

At its core, ESDM incorporates key behavioral teaching elements—including antecedent-behavior-consequence sequences, shaping, fading, and prompting—within a relationship-oriented context. The model is operationalized through a 13-item fidelity checklist that ensures consistent implementation across settings. Through this synthesis, ESDM addresses a common criticism of traditional ABA approaches by creating a more enjoyable, play-based therapeutic environment.

The theoretical foundation of ESDM emphasizes the critical role of active experiential learning, early interaction, and social motivation in child development. Subsequently, behavior change is targeted within “joint activity routines”—play activities and daily routines built upon the child’s initiative and preferences. These routines mirror the natural exchanges between typically developing children and their caregivers, wherein adults scaffold the acquisition of new behaviors during face-to-face interactions or object-centered activities.

Parent-Coached Home-Based Sessions

Parent involvement represents an essential component of the ESDM framework. Research demonstrates that high-quality caregiver coaching leads to improved parent responsiveness and enhanced child communication. Beyond skill development, parent participation promotes increased self-efficacy and reduced caregiver stress.

The parent-coaching protocol consists of structured sessions where caregivers learn to implement ESDM techniques within everyday interactions. A detailed parent manual covers ten intervention themes: social attention and motivation, sensory social routines, dyadic engagement, non-verbal communication, imitation, antecedent-behavior-consequence relationships, joint attention, functional play, symbolic play, and speech development.

Typically, coaching sessions break into distinct periods. Initially, parents share their experiences practicing techniques at home, followed by demonstration of preferred play activities. Thereafter, therapists provide feedback on parent implementation and introduce new strategies through modeling and guided practice. Each session concludes with an action plan identifying specific daily routines where parents can embed the targeted skills.

Daily Routine Embedding for Skill Reinforcement

The ESDM distinctively embeds teaching opportunities within the child’s natural environment and daily routines. Rather than creating artificial learning scenarios, the model incorporates intervention strategies into everyday activities such as mealtime, bathing, and play. This approach serves multiple purposes: it enhances skill generalization, reduces caregiver burden, and creates consistent learning opportunities throughout the day.

The structure maintains a predictable framework that ensures consistency while remaining flexible enough to accommodate the child’s preferences and family routines. For instance, meal preparation becomes an opportunity to build language and social skills, while grocery shopping develops problem-solving abilities. Clean-up routines transform into games that foster responsibility and organization.

Essentially, ESDM strategies aim for generality through teaching objectives within daily routines in natural settings. Each treatment objective includes a “generalization statement” specifying how the target behavior must be observed across people, tasks, and environments. Consequently, children learn to apply skills flexibly rather than in limited contexts.

The comprehensive nature of ESDM—coupled with its emphasis on relationships, play-based learning, and natural environments—positions it as a powerful early intervention approach for children with autism spectrum disorder. Through systematic implementation across home, clinical, and educational settings, the model addresses the core challenges of autism while building upon each child’s unique strengths and interests.

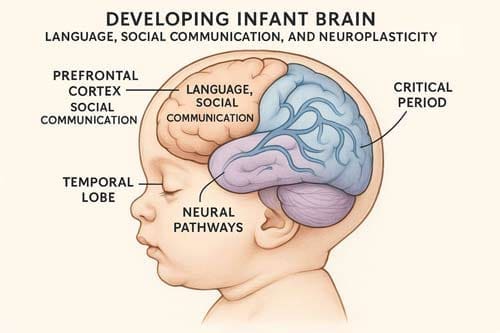

Neuroplasticity and the 18-Month Window of Opportunity

Neuroplasticity provides the biological foundation for early intervention effectiveness in autism spectrum disorder. This remarkable brain capacity enables structural and functional changes in the nervous system, allowing children to learn, remember, and adapt through experience. Understanding these neural mechanisms helps explain why interventions started at younger ages yield superior outcomes.

Sensitive Periods in Brain Development

The human brain exhibits heightened plasticity during specific developmental windows. The first year of life represents a period of extraordinary neural growth, with brain size doubling—creating an optimal opportunity for intervention. This plasticity occurs through regulation of genetic, molecular, and cellular mechanisms that influence synaptic connections and neural circuit formation.

Brain development follows distinct sensitive periods when environmental stimuli most potently shape cortical circuitries responsible for acquiring different abilities. These critical windows enable experience-dependent modification of neural structures that, once closed, become increasingly resistant to change. For children with ASD, early intervention during these sensitive periods proves imperative in shaping the brain to be receptive to social interaction.

Research demonstrates that autism often emerges from unfavorable factors affecting central nervous system development during these critical periods, resulting in impaired neural structure and function. Abnormalities in neuroplasticity found in ASD brains potentially lead to atypical neuronal connectivity and circuit formation, affecting information transmission between brain regions.

Neural Adaptation through Repetitive Social Learning

Neural adaptation—how brain responses change with repeated stimulation—functions differently in individuals with ASD. Whereas neurotypical adults adapt quickly to non-vocal sounds (5-8 repetitions) compared to vocal sounds (12-14 repetitions), autistic adults demonstrate the opposite pattern, adapting faster to vocal than non-vocal sounds. Moreover, emotional content uniquely influences neural adaptation in autistic individuals, suggesting heightened sensitivity to emotional cues.

This altered adaptation manifests behaviorally through reduced habituation across diverse domains, including tactile stimulation, face discrimination, and gaze direction. In neurotypical development, infants form representations about social events and their reward value through simultaneous coordination of communication, behavior regulation, and affective expression. Nevertheless, these foundational skills develop differently in autism.

Effective interventions leverage repetitive social experiences to reshape neural connections. The Early Start Denver Model, for instance, produces behavioral improvements through changes in brain structure and function that are particularly achievable during early life critical periods. Such interventions function as treatments that enhance neuroplasticity, capitalizing on the brain’s experience-expectant properties.

Why Earlier is Better: Cognitive and Language Gains

Starting intervention before 18 months offers distinct advantages given that autism symptoms typically emerge around this age. This timing coincides with heightened neuroplasticity before potentially faulty circuits become fixed. Evidence confirms early intervention can mitigate symptom severity and even reverse certain autism manifestations.

The benefits extend beyond symptom reduction. Children receiving early interventions demonstrate enhanced IQ levels, more adaptive behavior, and fewer ASD symptoms by age six. Furthermore, early comprehensive treatment models enhance language skills, though outcomes still typically differ from typical development.

Early intervention targeting autism symptoms has shown greater effects on repetitive behaviors in younger versus older children. These behavioral improvements stem from experience-dependent neuroplasticity—the brain’s fundamental capacity to reorganize through interaction with the environment. Research reveals that repetitive and stereotypical behaviors can appear by 12 months, making early intervention crucial for addressing these emerging symptoms.

Ultimately, the 18-month window represents a pivotal opportunity. The brain remains malleable throughout life, but intervention during periods of maximum plasticity offers the strongest potential for reshaping neural circuits critical for social and cognitive development.

Comparative Outcomes: ESDM vs Community-Based Programs

Research comparing ESDM with traditional community-based interventions reveals substantial differences in developmental outcomes across multiple domains. These comparative results provide a quantitative basis for understanding how specialized early intervention approaches outperform standard care options.

IQ Gains: 18 Points vs 4 Points

Children receiving ESDM intervention demonstrate markedly greater cognitive improvements compared to those in community-based programs. Meta-analyzes show children in ESDM intervention groups experienced an average IQ increase of approximately 17-18 points, representing more than one standard deviation of improvement. In contrast, children receiving community interventions showed modest gains of approximately 4 points. This disparity represents a cognitive development advantage that persists beyond the intervention period.

The cognitive benefits appear consistent across multiple studies. A robust variance estimation meta-analysis calculated an overall effect size of g = 0.412 for cognition (p = 0.038), confirming that children receiving ESDM made substantially greater progress in cognitive development than control groups. A separate meta-analysis revealed a moderate effect size of g = 0.28 for cognitive improvements.

These cognitive advantages remained stable throughout follow-up assessments. Indeed, two years after intervention began, the ESDM group maintained its developmental trajectory and continued showing improvements compared to baseline measures. This suggests that early cognitive gains translate into sustained developmental advantages.

Language Development: Receptive and Expressive Metrics

Perhaps even more striking are the differences in language acquisition between intervention approaches. Children receiving ESDM showed superior development in both receptive and expressive language skills compared to community intervention groups.

Meta-analytic data indicates a moderate effect size of g = 0.408 (p = 0.011) for language development, highlighting the ESDM’s effectiveness in improving communication skills. Another analysis found a similar effect size of g = 0.29 (p = 0.048). These consistent findings across studies underscore the reliability of language gains with ESDM intervention.

The disparity between receptive and expressive language development is especially noteworthy. Whereas community interventions produced some improvements in receptive language, the gap in expressive language development was considerably wider. This distinction proves vital, as expressive language skills directly impact a child’s ability to communicate needs, form relationships, and function independently in social settings.

Interestingly, although language improvements were evident, outcomes for social communication specifically showed minimal differences between groups (g = 0.01, p = 0.92). This finding suggests that while ESDM enhances language capabilities overall, certain aspects of social communication may require additional targeted intervention approaches.

Diagnosis Shift: Autism to PDD-NOS in 7 Children

Beyond quantitative improvements in specific developmental domains, ESDM intervention resulted in actual diagnostic changes for some children. Henceforth, this represents perhaps the most compelling evidence for early intervention’s impact.

Following ESDM intervention, 29.2% of children (7 children) experienced a diagnostic shift from autism to pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS). In comparison, only 4.8% (1 child) in the community intervention group showed similar diagnostic improvements. This fivefold difference illustrates how intensive, targeted early intervention can alter the developmental trajectory enough to change diagnostic classification.

Overall, ESDM intervention also produced improvements in autism symptomatology. Meta-analysis revealed an effect size of g = 0.27 (p = 0.04) for reduction in autism symptoms. This indicates that beyond improving specific skills, ESDM helps address core autism features.

The long-term implications of these comparative outcomes extend beyond immediate developmental gains. Children who received ESDM demonstrated a continued developmental trajectory more closely resembling typical development, whereas the community intervention group showed increasing delays in adaptive behavior over time. Furthermore, post-intervention service costs were lower for the ESDM group than for children who received community-based services, suggesting economic benefits alongside developmental advantages.

These comparative outcomes underscore why specialized early intervention approaches like ESDM yield superior results compared to general community-based interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder.

Parental Role in Early Intervention Success

Parental involvement represents a cornerstone of successful early intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder. Studies consistently demonstrate that caregivers who implement therapeutic strategies during daily interactions produce lasting improvements in their children’s development.

Parent Training and Coaching Modules

Parent-mediated interventions for early intervention autism utilize structured approaches to teach caregivers effective techniques. The ESDM parent manual, for instance, outlines ten essential intervention themes:

- Social attention and motivation

- Sensory-social routines

- Dyadic engagement

- Non-verbal communication

- Imitation

- Learning fundamentals (ABCs)

- Joint attention

- Functional and symbolic play

- Speech development

Parent coaching sessions typically follow a systematic format. Initially, caregivers share experiences practicing techniques at home, followed by demonstration with their child. Therapists then provide feedback and introduce new strategies through modeling and guided practice. Each session concludes with an action plan identifying specific daily activities where parents can embed targeted skills. This structured approach enables parents to master techniques progressively.

Research confirms that high-quality caregiver coaching leads to improved parent responsiveness and enhanced child communication skills. Beyond skill development, parent participation promotes increased self-efficacy and reduced caregiver stress.

Capturing Attention and Promoting Communication

Parents learn specific techniques to engage their children’s attention and foster communication development. Effective strategies include positioning at the child’s eye level, following the child’s lead in play activities, and imitating the child’s actions to capture interest. Through these approaches, parents create opportunities for joint attention—a critical foundation for communication development in early intervention ASD.

Responsive interaction techniques teach parents to join their child’s focus and build on interactions in a non-demanding style. This approach emphasizes child choice while parents provide contingent language and actions. Parents also learn to establish routines with familiar, repetitive language and strategic pauses that encourage communicative attempts.

Consistency Across Home Environments

The benefits of early intervention autism are maximized when techniques are applied consistently across all environments. Active caregiver involvement enhances therapy effectiveness, as parents who maintain regular communication with therapists can identify behavioral triggers and adapt strategies accordingly. This consistency creates a supportive framework that reinforces learning across settings.

Establishing structured routines with visual supports helps children predict what comes next, reducing anxiety and encouraging focus. Parents trained in intervention techniques implement them confidently during daily activities, ensuring that skills learned during therapy sessions generalize to natural environments.

Studies show that parents consistently implementing ESDM strategies at home helped their children progress from primarily object-focused engagement to increased levels of joint engagement with maintained improvements over one-year follow-up. This evidence underscores how parental consistency amplifies the effectiveness of early autism diagnosis and intervention.

Challenges and Ethical Considerations in Early Diagnosis

Despite promising outcomes of early autism interventions, the diagnostic process presents complex challenges worthy of careful consideration. This section examines critical ethical dilemmas surrounding early identification efforts.

Risk of Overdiagnosis and Labeling

Concerns about potential overdiagnosis have emerged as ASD prevalence rates continue rising, with California-specific prevalence reaching 4.5% in recent CDC surveys. Certainly, evidence suggests some community diagnoses may be inaccurate—one study found that of 232 children with existing community ASD diagnoses, only 47% met research criteria upon comprehensive re-evaluation. Several factors contribute to this issue. First and foremost, screening tools designed for toddlers often produce high false-positive results, leading to unnecessary referrals for further assessment. In practice, ADOS scoring practices sometimes involve counting abnormal behaviors without establishing their specific autistic quality, potentially pathologizing behaviors that aren’t typical but aren’t necessarily autism-related. At the individual level, incorrect labeling can constrain a child’s social and educational experiences while affecting identity formation.

Emotional Burden on Families

The diagnostic journey places substantial stress on families. Parents of children with ASD report higher objective and subjective burden compared to other parents. In addition to psychological distress, these families face numerous practical challenges—disturbed family relationships, constraints in social and work activities, and substantial financial difficulties through healthcare expenses and employment impacts. Mothers typically experience greater subjective burden than fathers. Parents often describe feeling alone while navigating complex healthcare systems. Interestingly, alongside difficult emotions like shock, grief, and worry, the most frequently cited reaction to diagnosis is relief—providing an explanation for behaviors and access to support services.

Balancing Early Action with Diagnostic Accuracy

Currently, a troubling gap exists between when diagnosis is possible and when it typically occurs. While reliable diagnosis can happen in a child’s second year, the median diagnostic age in the United States remains 49 months. This delay primarily stems from:

- Specialist shortages and metropolitan clustering creating access barriers

- Labor and cost-intensive evaluation processes

- Knowledge gaps about early ASD signs among professionals and families

- Socioeconomic factors affecting implementation

Increasingly, community-based approaches enhancing primary care providers’ diagnostic capacity show promise for reducing these delays. However, concerns persist about diagnostic accuracy, particularly in differentiating ASD from global developmental delay. Ultimately, for every three ASD cases detected, two cases reach adulthood without treatment, underscoring the importance of balancing early action with diagnostic precision.

Conclusion

Early intervention strategies for autism spectrum disorder have demonstrated remarkable efficacy, particularly when implemented during critical developmental windows. The evidence presented throughout this article underscores how interventions beginning around 18 months of age yield substantially better outcomes than delayed approaches. These findings align with our understanding of neuroplasticity—the brain’s extraordinary capacity to reorganize neural connections most effectively during specific developmental periods.

Research conclusively shows the Early Start Denver Model outperforms traditional community-based interventions across multiple developmental domains. Children receiving ESDM intervention experienced cognitive improvements averaging 18 points versus merely 4 points in community programs. Similarly, language development gains proved markedly higher with specialized early intervention. Perhaps most compelling, diagnostic shifts occurred for 29.2% of ESDM participants compared to only 4.8% in community intervention groups.

The neurobiological mechanisms underlying these improvements deserve attention. Sensitive periods in brain development create optimal windows for intervention, especially before age two when neural circuits remain highly malleable. Targeted interventions capitalize on this neuroplasticity, establishing foundations for social communication and cognitive development that become increasingly resistant to change as children age.

Nevertheless, successful outcomes depend heavily on parental involvement. Caregivers who consistently implement therapeutic strategies during everyday interactions substantially enhance intervention effectiveness. Structured parent coaching modules equip families with techniques for capturing attention, promoting communication, and maintaining consistency across home environments.

Despite promising results, numerous challenges persist. Practitioners must balance early action with diagnostic accuracy while acknowledging the potential risks of overdiagnosis. Additionally, healthcare systems must address the emotional burden families experience throughout the diagnostic and intervention process.

Moving forward, expanding access to evidence-based early intervention programs represents an urgent priority. Though reliable diagnosis can occur during a child’s second year, the median diagnostic age remains approximately 49 months—a troubling gap that delays critical intervention. Practitioners equipped with knowledge about early autism signs can help narrow this gap, connecting families with interventions during optimal developmental windows.

Therefore, the combined evidence paints a clear picture: early intervention for autism—particularly when implemented around 18 months—offers children the best opportunity for improved developmental trajectories and quality of life. Though challenges remain, the documented 87% success rate provides compelling justification for continued investment in early identification and intervention programs.

Frequently Asked Questions:

FAQs

Q1. What is the Early Start Denver Model (ESDM) and how effective is it? The Early Start Denver Model is an evidence-based early intervention approach for children with autism that combines behavioral and developmental strategies. Studies show it has an 87% success rate when started at 18 months, with participants experiencing significant improvements in IQ, language skills, and autism symptoms compared to traditional interventions.

Q2. How does early intervention impact brain development in children with autism? Early intervention capitalizes on neuroplasticity – the brain’s ability to form new neural connections. When started before age 2, interventions can shape brain circuits during critical developmental periods, leading to improved social, communication, and cognitive skills. This window of opportunity becomes less flexible as children age.

Q3. What role do parents play in early autism intervention? Parents play a key role in early intervention success. They receive training to implement therapeutic strategies during daily routines, which helps reinforce skills and generalize learning across environments. Consistent parental involvement leads to better outcomes in child development and reduced caregiver stress.

Q4. Are there risks associated with early autism diagnosis and intervention? While early intervention is beneficial, there are concerns about potential overdiagnosis and the emotional burden on families. Screening tools for toddlers can produce false positives, and misdiagnosis may affect a child’s social experiences. However, the benefits of early intervention generally outweigh these risks when diagnosis is accurate.

Q5. How soon can autism be reliably diagnosed, and why is early diagnosis important? Autism can be reliably diagnosed as early as a child’s second year. Early diagnosis is crucial because it allows for intervention during critical developmental periods when the brain is most plastic. However, the current median age of diagnosis in the US is 49 months, highlighting the need for improved early detection and intervention access.

References:

[1] – https://acamh.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jcpp.13806

[2] – https://therapyworks.com/blog/language-development/improving-joint-attention-children-autism/

[3] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11079289/

[4] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9857540/

[5] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9542560/

[6] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3487718/

[7] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10469633/

[8] – https://www.cureus.com/articles/169662-early-diagnosis-of-autism-spectrum-disorder-a-review-and-analysis-of-the-risks-and-benefits

[9] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5789210/

[10] – https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/

fnins.2016.00139/full

[11] – https://www.jneurosci.org/content/42/13/2804

[12] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4163495/

[13] – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S138824572400364X

[14] – https://elifesciences.org/articles/36493

[15] – https://www.science.org/content/article/rewiring-autistic-brain

[16] – https://www.aaas.org/news/autism-research-reveals-benefits-early-intervention-rapid-detection

[17] – https://www.re-origin.com/articles/neuroplasticity-children-with-autism

[18] – https://www.disabilityscoop.com/2019/04/09/study-questions-autism-therapy/26374/

[19] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4064565/

[20] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7349854/

[21] – https://www.cebc4cw.org/program/early-start-denver-model/detailed

[22] – https://asatonline.org/for-parents/becoming-a-savvy-consumer/is-there-science-behind-that-early-denver-model/

[23] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3888483/

[24] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5683273/

[25] – https://www.discoveryaba.com/aba-therapy/the-importance-of-consistency-across-all-caregivers-in-aba-therapy

[26] – https://www.crossrivertherapy.com/autism/how-to-ensure-consistency-between-center-based-and-at-home-aba-therapy

[27] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6080067/

[28] – https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40489-021-00237-y

[29] – https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/152/2/e2023061188/192793/

Diagnostic-Accuracy-of-Primary-Care-Clinicians

[30] – https://www.demneuropsy.org/article/the-challenges-for-early-intervention-and-its-effects-on-the-prognosis-of-autism-spectrum-disorder-a-systematic-review/

[31] – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10901562/